A full copy of this paper can be obtained from the author, Dr. Daniel Jiang at the Center for Performance Management Research and Education (CPMRE): daniel.jiang@uwaterloo.ca

Introduction

Over the past twenty years, and especially since the financial crisis of 2008-2009, firms have paid greater attention to their cash flow. Many have introduced executive incentives designed to encourage better cash flow performance. This research examines whether these incentives work, and whether the presence of such incentives leads to other benefits for the firm. Foremost, the researchers explore interest rates on business loans and whether banks offer significantly better terms where CEOs are incentivized – as part of their compensation – to improve cash flow performance.

These are important questions because US firms rely a great deal on banks for external financing. And when a company has the cash flow it needs to finance its initiatives without turning to outside (and more expensive) sources of financing, it can create a virtuous cycle whereby even more cash flow is generated.

Through an extensive and robust series of data analyses designed to control for multiple factors that might contribute to the connection between cash flow measurement (CFM) incentives and better loan terms, the researchers reveal some interesting and surprising results. As expected, banks like strong cash flow performance among firms they have lent money to because it reduces the risk of loan defaults. Surprisingly though, they don’t reward strong cash flow performance alone. They prefer to see a CFM incentive plan in place – the longer and stronger the better – and will reward such plans with significantly better interest rates on loans ahead of actual cash flow performance.

Finally, the researchers determine that the faith banks place in firms which incentivize better cash flow is not misplaced. CEO cash flow incentives work (i.e., cash flow performance improves significantly in firms that introduce the incentives) and the same firms are significantly less likely to default on their loans.

Methodology

The researchers analyzed data from 4,562 loans taken by 810 very large US-based public firms between 1999 to 2012. 224 of these firms used cash flow incentive plans for at least one year in that period. A control group of 586 firms was used for comparison; this group took on similar loans but with no cash flow incentive plans in place at all during the same period.

The researchers acknowledge that business lending is complex, and that any number of factors might cause a bank to offer one client better terms than another. For example, firms may enjoy lower borrowing rates based on having a long-term relationship with a bank. The size and length of the loan, and factors that impact a firm’s credit risk will influence its borrowing rate. Moreover, they raise the concern that cash flow incentives might be adopted specifically to get better loan terms from a bank (i.e., that the possibility of better loan terms leads to CFM programs rather than the other way around). The researchers control for these factors using advanced statistical analysis techniques to separate the various potential influencers, and to isolate the effects of CEO cash flow incentive plans on the interest rates banks offer on loans.

Key Findings

- Where CEOs are incentivized to improve cash flow performance, they do. CEOs are very likely to make the types of decisions and drive the types of behaviors across the firm that result in faster turnover of inventory and faster collection of accounts receivable – among other things – which result in better cash flow performance.

- In terms of economic significance, the use of CFM incentives is associated with a reduction in loan spreads of about 13 basis points on average.

- This spread is significantly larger for firms that use the incentives for at least two years running (showing a greater commitment to the practice). However, the effects remained regardless whether firms keep using cash flow-based metrics in the following two years.

- Most firm’s compensation policy tends to be very sticky. They rarely experience dramatic changes in adjacent years. For example, among firms that use cash flow-based metrics in year one, 75% continue using the same measure in the following three years.

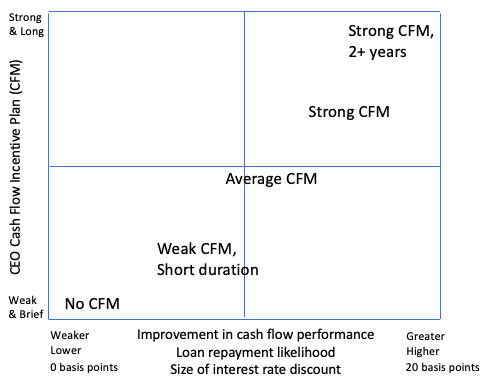

- The interest rate advantage is larger still for firms that also tie a higher percentage of CEO compensation to improved cash flow performance (Fig.1).

- Lower rates do not accrue to firms that actually exhibit better cash flow unless they have an incentive plan in place!

- Thus, banks appear to predict better cash flow and less likelihood of a firm defaulting on their loan when a firm incentivizes its CEO based on cash flow performance.

- The research suggests that banks are correct. Firms that use CEO incentives based on cash flow performance are significantly less likely to default on their loans (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Longer and stronger incentive plans generate larger benefits.

Takeaways

- Any organization that desires greater cash flow should consider incorporating cash flow performance incentives into CEO compensation. These incentives work in most firms.

- Organizations that wish to attract better interest rates on bank loans should consider incorporating cash flow performance incentives into CEO compensation. Banks appear to take these incentives as a strong signal of the firm’s ability to repay the loan.

- The greater the advantage sought, the stronger the CEO incentive should be (as a percentage of total compensation) and the longer the firm should run the incentive program. The average firm that uses CFM incentives gains a 13-point advantage in interest rates but those that have been doing it for two or more years, and base more of the CEO’s compensation on the incentives, achieve a 20-basis point advantage, on average. Again, banks appear to interpret these practices as evidence of a firm’s likelihood to repay the loan.

Q & A

We asked the authors the following questions about their research.

-

This research discovers that banks offer better borrowing terms to companies that incentivize CEOs around improving cash flows. Is it equally important that you found that executive cash- flow incentives work to increase cash flow (move inventory faster, collect receivables sooner, etc.) and that banks believe so strongly in this that they advance the reward (lower interest rates) before they even see the gains (better cash flow performance)?

This is a great takeaway. In a larger picture, I think our study provides evidence supporting the “optimal contracting” theory in the compensation literature in contrast to the “rent extraction” theory. In other words, the cash flow-based performance measures are included in the contract to motivate CEOs to improve company’s cash flow performance, not to facilitate the CEO exploiting his/her personal interests. From the bank’s perspective, it seems to us that banks understand firms’ intentions well. They can see through the reasons firms include cash flow metrics in their CEO compensation contract and reward firms accordingly.

2. Do you think the effects (better loan terms) would be even stronger if the cash flow incentives were expanded to other key executives – the CFO for example, and beyond to the CMO, COO, CHRO, etc.?

This is a very interesting and very important question to answer. Without the data, I am not sure about the answer because it is possible that CEOs and other top executives have different sets of performance measures in their contracts. I am interested in exploring the answer to this question in the future.

More questions? Please send any additional questions to the researchers: Daniel Jiang at: daniel.jiang@uwaterloo.ca; Guojin Gong at: gug3@psu.eud, or Biqin Xie at: bxx5@psu.edu.