A full copy of this paper can be obtained from the author, Dr. Christopher Wong (chrwong@wlu.ca).

Summary

Employers regularly promise employees rewards contingent on their performance. Cash bonuses, gifts and recognition are used to incentivize workers in the hopes that they will increase effort and performance toward goals. It is not uncommon, however, that unforeseen events (e.g., natural disasters, pandemics) interfere with employees’ ability to meet their goals. In these cases, they may lose their chance to earn some or all of a reward through no fault of their own.

At their discretion, employers can make changes to incentive programs to account for unforeseen events that negatively impact employees’ ability to earn rewards. More than 75% of firms, however, choose not to make such adjustments, and of the minority that do, most do so within the parameters of the reward budgets originally designated. Unless a firm is willing to increase reward budgets, attempts at achieving equity by adjusting goals to account for unforeseen events proves complex and time-consuming; and it is fraught with the risk of pleasing one set of employees while disappointing others.

In many cases, it is easier, safer and more practical not to adjust incentive and reward programs to account for detrimental factors outside employees’ control. At the same time, impacted employees are well aware that leaders could help them by adjusting goals to account for unforeseen events, if they choose to. When leaders fail to do so, impacted employees may grow resentful or mistrustful, affecting their engagement at work and their performance.

In summary, the author discovers that where employers take relatively simple actions to explain their reasons for not adjusting incentives, and – especially – where they go further to help impacted employees see the problem from their (management’s) perspective, negative feelings and performance impacts can be reduced or even eliminated.

At the time of writing, this research coincided with the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, making the author’s findings especially salient for firms struggling to recover. Employees’ ability to achieve performance goals associated with incentive programs devised for 2020 were, in most cases, negatively impacted due to the effects of COVID-19. Moreover, most organizations will have suffered financially due to the pandemic, reducing their willingness and ability to adjust performance goals so that employee can earn rewards.

Whatever the disruption, this research offers new and compelling evidence that firms should ensure that employees understand the reasons for the decisions their leaders make, and not take that understanding for granted. Perceptions of equity and fairness are always among the most potent drivers of employee engagement and performance. The author’s simple, free or inexpensive remedies might save organizations tremendous costs and pain.

Assumption/Hypotheses

The author proposes that where events or circumstances occur outside an employee’s control, and which impact that employee’s ability to earn a reward (e.g., bonus); and where the rules and goals for earning that reward were set prior to the unforeseen event, then affected employees’ perception of the firm’s fairness will decrease where adjustments are not made (i.e., where the employer chooses not to help). Moreover, this perception of unfairness will negatively impact affected employees’ performance.

The author further proposes that should leaders explain their reasons for not making adjustments, and should the leadership take measures to help employees assess the decision from management’s perspective, perceptions of unfairness will be mitigated as will the impact on performance.

The Experiments

The researcher conducted a series of laboratory experiments involving 169 participants (students) from two large Canadian universities. Participants were assigned into one of four non-control groups or into one control group. In each of the non-control groups, participants were given clear and simple counting or decoding-type tasks for which they received standard pay. They were also promised a bonus should they achieve certain performance goals. Participants were told that the goals could be adjusted downward in case of unforeseen events that impacted their ability to reach their goals, but that the total rewards available could not change (i.e., downward adjustments to their goals would have to be offset by upward adjustments to other participants’ goals).

Participants in each of the four groups experienced events during the experiments that negatively impacted their ability to achieve their goal(s) and to earn the reward. At various points in the experiment their tasks became significantly more difficult before leveling back to the norm.

Despite the disruptions, adjustments to goals were not made (except to a randomly selected 15% of participants in the groups). The experiments, after all, were focused on what happens when adjustments are not made by firms following unforeseen negative events. Conditions in each of the groups differed in the following ways:

- In Group 1, brief explanations were given for the leader deciding not to make adjustments.

- In Group 2 no explanations were provided.

- In Group 3, a simple perspective-taking exercise was performed before the tasks to help participants understand the fairness-related challenges leaders face in deciding whether to make adjustments when total reward budgets cannot change.

- In Group 4, no perspective-taking exercise was performed (nor any explanation given).

- Group 5 was a control group in which participants were not told that the goals could be adjusted if unforeseen events occurred.

Results

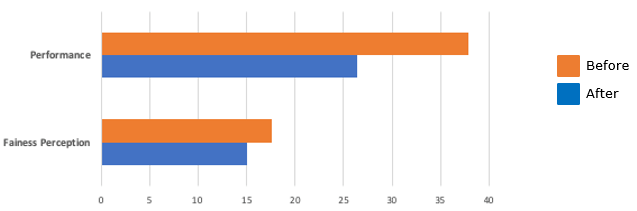

Results from the experiments revealed significant drops in participant perceptions of fairness and in performance when leaders failed to make adjustments to goals following unforeseen events that negatively impacted participants’ ability to meet their goals and earn a reward (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Performance and Fairness Perception before and after a leader did not adjust goals.

The results fail to support the author’s first hypothesis, however, because the control and non-control groups share the same results. Declines in perception of fairness and in performance, while significant, cannot be attributed to participants’ observation of leader’s inaction or failure to help. The results do support the author’s expectation that when leaders take the time to explain their decision not to adjust goals, participants perceptions of fairness are not as negatively impacted as when no explanation is provided. However, explanations alone may not reduce negative impacts on performance.

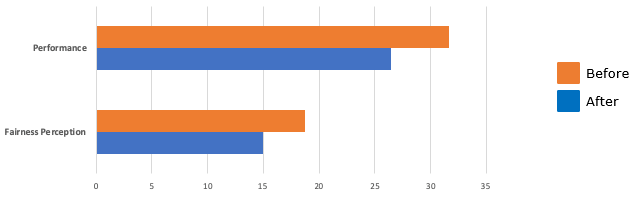

Importantly, participants who performed the quick and basic perspective-taking exercise (in which they attempted to adjust goals and rewards for two employees - taking from one to give to the other) perceived greater fairness after a leader decided not to adjust goals than did those who did not perform the exercise. Indeed, those participants who performed the perspective-taking exercise perceived even greater fairness than those who were not at all impacted by a negative decision by management (Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, after a decision not to adjust goals, perspective-trained participants significantly outperformed those who did not receive the training (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Performance and Fairness Perception with and without perspective-taking training

Key Takeaways

- According to Salary.com, more than three-quarters of US organizations use performance-contingent incentives. Ultimately, they do so to drive higher performance.

- In most cases, organizations choose not to adjust incentive program goals, even after events occur that make employee goal attainment more difficult. These decisions often breed resentment among impacted employees causing their performance to suffer.

- Simply explaining the decision not to make goal adjustments ameliorates negative perceptions of fairness (i.e., resentment) but may not, on its own, effect performance.

- Perspective taking, on the other hand, not only eliminates negative effects on affected employees’ perceptions of fairness, it slightly improves those perceptions. This, in turn, appears to almost entirely eliminate performance declines that otherwise accompany leaders’ decisions not to adjust goals.

Q & A

We asked the author the following question about their research.

-

Dr. Wong, your interventions – a simple explanation and a basic perspective-taking exercise – seem like easy, inexpensive interventions to avoid considerable potential damage. Why wouldn’t every firm adopt them? Also, if leaders repeatedly decide not to make goal adjustments, won’t the effects of the explanation and perspective-taking exercises wear off?

Though both these interventions can be cheap and simple to implement, there are important considerations. The explanation must be perceived as sincere (among other things) - this is something I had to test a couple times in the lab to get right. Similarly, the perspective taking exercise has to be designed in a way to help employees understand "what they're missing" - again, this took a couple of tries in the lab to get right. To answer the second part of your question, yes, leaders should probably be careful to make changes from time to time, or else their explanations and exercises will not be received as credible by employees.

More questions? Please forward any additional questions you may have to the author, Dr. Christopher Wong at the Lazardis School of Business and Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University: chrwong@wlu.ca.