Shaar Hashomayim synagogue, Windsor -- with Doors Open balloons

We’ve been talking about churches — or more broadly, places of worship of all descriptions — and wondering how public policy should respond to the conservation dilemma they pose. But first we need to better understand their special circumstances.

My first experience with the preservation of a church was in 1979 when I was a summer student with the Stratford Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee (or LACAC — remember them?). There was a call from someone from Trinity Anglican Church in the village Sebringville, just west of Stratford. The congregation wanted advice on something. While Sebringville was “out of our jurisdiction”, Stratford’s was the only nearby LACAC and I was sent out to have a look. What I saw was a beautiful little white board-and-batten, “carpenter gothic” building from 1887.

Trinity Anglican Church, Sebringville -- Courtesy Fanshawe Pioneer Village

I don’t recall exactly what the parish was thinking to do… but it was something rather awful. Could it have been — gasp — a dreadful plan to replace the board-and-batten with aluminum siding? Whatever it was, we helped talk them out of it, arguing for retention of its historic appearance and repair of original features rather than removal or covering up. By 1988 the building’s heritage value was formally recognized and it was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act.

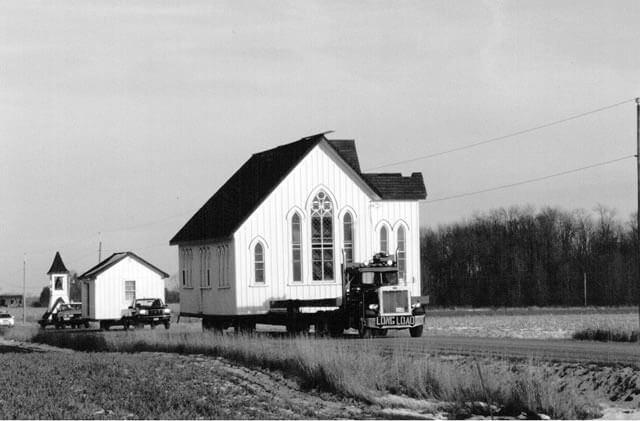

But… by 1997 the dwindled congregation voted to close the church. It looked like demolition was at hand. In the end the building was moved from its site on Highway 8 (the old Huron Road) about 55 km south to Fanshawe Pioneer Village, on the north side of London, where it continues in use for weddings and other special events.

Trinity Church on the move, in three parts -- Courtesy Fanshawe Pioneer Village

Like all buildings moved out of their original surroundings and relocated to a “pioneer village” — an artificial and sometimes haphazard arrangement of collected orphaned buildings — Trinity today evokes mixed feelings. But though its context has been lost, the church itself was saved — unlike many! — and, now in public ownership, it continues to be cared for, used and interpreted.[1]

It sure seems like our historic places of worship have more than their fair share of challenges. The main thing of course is declining congregations and attendance and the desire for smaller, lower maintenance buildings and often different, less formal meeting spaces. And then, when worship wanes, there are the typically formidable obstacles to adaptive re-use of the buildings. These can be attitudinal — certain faith organizations would rather have their churches deconsecrated and destroyed than sold and re-used for an unpredictable and, in their view, unsavoury secular purpose… remember the “porno movie house” cartoon from last time? But mainly it’s the sheer physical challenge of re-purposing the large open interiors of many churches. (The small, rural ones tend to be easier — who hasn't known someone who lived in an old church?)

Adding to the adaptive re-use complications is that these interiors are special! Unlike most heritage homes, commercial blocks or factories, the historic church/synagogue/mosque/temple is usually as significant inside as outside. Which is why designations and heritage easements on these buildings almost always cover interior features as well.

Interior of the Church of Our Lady Immaculate, Guelph

Interior of Romanian Orthodox Church, Windsor

While we’re talking of church interiors — not to be forgotten is the point that religious buildings that continue as places of worship may require changes for liturgical reasons over time, and this can give rise to tension with heritage conservation.

Then there’s the fact that ownership and control of houses of worship varies considerably, with some faith organizations much more centralized (like the Roman Catholic Church) and some much less so (like the United Church).

So… lots of ways in which places of worship are special, if not unique. And here’s yet a couple more to keep in mind — they’re exempt from property tax; and faith groups as non-profit organizations are generally exempt from income taxes as well.

Does all this add up to the need for distinct policy responses for the conservation of Ontario churches? Of course. Last time we saw an instance of this when the Ontario Heritage Foundation (now Ontario Heritage Trust) bent the rules on its conservation easements program to accommodate the particular concerns of church organizations. But what else has been done — or not done? For next time.

Notes

Note 1: The church may have been moved, but not the designation, which had to repealed when the building left Sebringville. It has not been re-designated on its current site.