Alumnus helped develop HPV vaccine

Waterloo kinesiology grad returns to campus to talk about being part of a team that worked to prevent cervical cancer

Waterloo kinesiology grad returns to campus to talk about being part of a team that worked to prevent cervical cancer

By Christine Bezruki Faculty of Applied Health SciencesPatrick Brill-Edwards never thought he would help develop the world’s first cancer vaccine. But by the time the Gardasil vaccine hit the market in 2006, he had done just that.

A Waterloo kinesiology graduate and trained medical doctor, Brill-Edwards joined Merck, the company behind Gardasil, in 2001 when the vaccine had not yet been granted licensure.

“From the results of a proof-of-concept study, we knew it worked,” he said. “It was just a matter of committing resources to getting it approved by regulatory health bodies.”

Vaccine almost 100 per cent effective against HPV

Over the next five years, Brill-Edwards worked with a team of researchers to show the world what scientists already knew — that Gardasil is almost 100 percent effective in preventing disease caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), including the second most common cancer among women worldwide, cervical cancer.

“Never before have scientists been able to prevent cervical cancer by using a vaccine,” he said.

“Cervical cancer is so common, especially in countries without pap screening. The vaccine has the potential to reduce the burden of illness and that’s huge.”

400 women die every year from cervical cancer

In Canada, almost 400 women die each year from cervical cancer, with 1 in 150 women expected to develop the disease during her lifetime.

Unlike traditional vaccines such as measles or yellow fever, Gardasil does not contain a live virus. Rather, the vaccine works by presenting the immune system with a way of recognizing what HPV looks like. If an individual becomes infected after receiving the vaccine, the immune system is able to quickly recognize and neutralize the virus.

On top of protecting against strains of the virus that cause cervical cancer, Gardasil helps protect against viruses that cause 80-90 percent of HPV-related anal cancers in men and women and 90 percent of genital warts.

The Gardasil controversy

Despite being a monumental medical breakthrough, when the vaccine was finally granted licensure and made available to the public in the spring of 2006, it was met with a firestorm of controversy.

From anti-vaccine groups citing unpleasant side effects to religious groups accusing the vaccine of causing promiscuity among youth, the vaccine made headlines around the world.

“From a science perspective there is no controversy. It’s safe, effective and strongly endorsed by public health professionals,” explained Brill-Edwards.

Vaccine offered to Grade 8 students in Ontario

While he admits it can be hard to understand the controversy surrounding his work, Brill-Edwards remains immensely proud of the vaccine, which is offered to all eighth grade students in Ontario.

“We have to be vigilant and point to evidence to refute claims, while always being open minded to new accusations. It takes a lot of commitment. There are no casual team members that work on a vaccine like Gardasil. But what doctor wouldn’t want to work on a team preventing cancer? It’s incredibly rewarding.”

Today Brill-Edwards lives in Haverford, Pennsylvania with his wife, Lisa, who also practices medicine. He will be on campus as the keynote lecturer for the University’s TD Discovery Days in Health Sciences event.

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

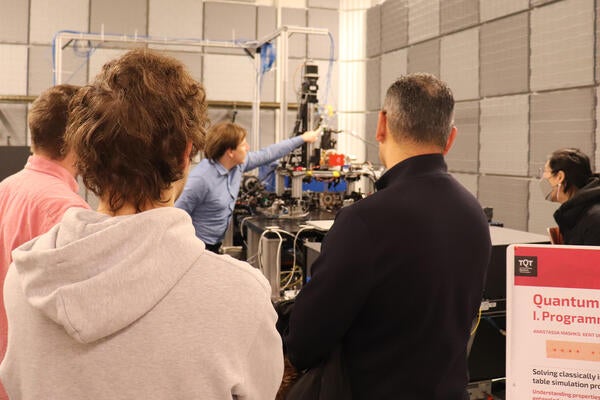

TQT Quantum Opportunities and Showcase sheds light on quantum research advancements, discoveries and real-world applications

Read more

Waterloo researchers collaborate with The Ottawa Hospital and other Canadian institutions on initiatives for public health, privacy and security

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.