PhD candidate Erinn Atwater, an expert in the Cryptography, Security, and Privacy group at the Cheriton School of Computer Science, has developed an Android app for reporters and activists so they can encrypt their smartphones to protect sensitive information before crossing the border.

Atwater and Cheriton School of Computer Science Professor Ian Goldberg created the app, Shatter Secrets, which splits a device’s password and sends it to friends, colleagues or acquaintances abroad, making it physically impossible for a person to unlock his or her phone at the request of a border agent.

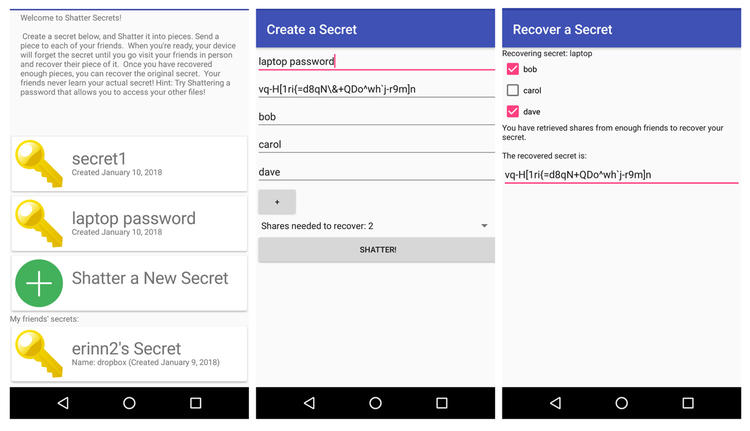

Shatter Secrets running on an Android device showing, from left to right, the list of created secrets and shares received from friends, the configuration screen for sharing a new secret, and a secret being recovered after retrieving shares from two of three friends.

Our electronic devices are filled with personal information, including conversations, photos and videos, medical information and passwords. But this same data makes our devices of interest to law enforcement officials even during routine searches.

“We argue that international border security agents have no business rifling through the intimate data stored on our personal electronic devices without a warrant or consent,” said Erinn, who also is the research director of Open Privacy Research Society, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to understanding, researching and serving the needs of marginalized and highly targeted at-risk communities. “By distributing encryption keys amongst trusted friends at the traveller’s destination before travel, the traveller cannot be compelled to provide access to their devices immediately.”

The idea for the app came to Erinn and her colleague Professor Goldberg after seeing reports of border agents, largely in the United States, asking for device or social media passwords as part of inspections.

“Shatter Secrets is deliberately intended for people such as journalists and activists who have high-value information and would rather be subjected to government questioning than give up the data they’re trying to protect,” she said.

As they report in their journal article describing Shatter Secrets, Erinn and Professor Goldberg found that the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency searched around 30,000 electronic devices in 2017, which led to 250 complaints about warrantless searches. While that proportion is small, it could be comprised disproportionately of people who would rather be refused entry than to forcibly surrender data.

Shatter Secrets uses threshold cryptography to distribute encryption keys into shares, which are then securely transmitted to friends residing at the traveller’s destination. If a traveler is asked to unlock their phone, he or she is physically unable to comply with demands to decrypt their device.

“We do not want people to be put in a position where they have to be lying, so one of the things we wanted to ensure is that when you say you cannot get your data, it is true,” said Professor Goldberg. “But even individuals who don’t cross borders or don’t think they have much to hide should be glad that there is a technique for journalists and activists to protect themselves. The protection of everybody’s civil rights and the protection of democracy hinges upon a free and open press and activists who are willing to push boundaries and affect social improvement.”

Open Privacy is an incorporated non-profit society in British Columbia that researches, builds and deploys technology that serves marginalized communities. Donations to Open Privacy help fund projects such as Shatter Secrets as well as research and day-to-day running costs.

To learn more about this innovative research and the app, read Erinn Atwater and Ian Goldberg’s paper, Shatter Secrets: Using Secret Sharing to Cross Borders with Encrypted Devices, which they presented at the 26th International Workshop on Security Protocols in Cambridge, UK, March 19–21, 2018.