Like many coastal lagoons around the world, Chilika Lagoon has faced problems that have seriously degraded its social and ecological base, with long-term impacts on the lives and livelihoods of its fishers. On the east coast of India within the Bay of Bengal, it is the largest lagoon in Asia, a Ramsar wetland of global conservation importance, and a productive fishing area with an estimated 400,000 fishers. Extensive tiger shrimp aquaculture and a new, artificially dredged sea mouth in the Bay of Bengal are major drivers of changes in livelihoods. Aquaculture directly influenced access rights and village fishery cooperatives through large-scale encroachment of customary fishing areas. The new sea mouth impacted species composition, fish habitat and productivity of the Lagoon. Both drivers acted synergistically, the sea mouth dredging amplifying fisher livelihood disruption due to aquaculture expansion, and the two together resulting in the loss of fisher livelihoods.

Methodology

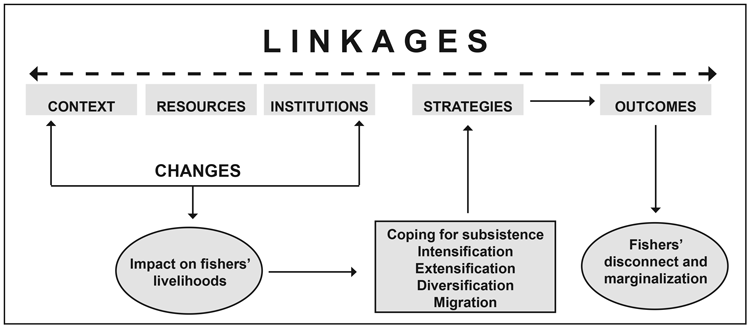

The sustainable livelihood framework (Fig. 1) is widely used to analyze changes in rural livelihoods, especially in resource-dependent communities. It emphasizes that given a certain situation where the livelihood context, resources and institutions remain favourable, people’s livelihood strategies can have one of two outcomes:

- outcomes are sustainable, with affected households given respite from the impacts of livelihood loss, and

- outcomes are insufficient in reversing livelihood crises and may not result in sustainable livelihood because of the associated complexities, uncertainties and multilevel drivers.

This paper aims to evaluate both possibilities with empirical data to clarify what may impede sustainable livelihood outcomes, despite well-planned strategies. The relationship between livelihood shocks and stresses, capitals, institutions and livelihood strategies is furthermore circular and not linear.

Figure 1: Sustainable livelihood framework: Examining the strategies and outcomes (Modified from Scoones 1998; Bebbington 1999)

Extensive household and village-level survey data were used to examine the processes of social-ecological change in Chilika. All surveys were in the local Odiya language, in which most villagers are well-versed. To survey all Chilika fisher villages, extensive collaboration with the Fisher Federation and other local contacts was required. In addition to the surveys, selected data for this paper came from semi-structured interviews, focus groups, multi-stakeholder consultations, and secondary sources including both village records and policy documents.

Outcomes

Considering that large-scale changes in the livelihood context, resources and institutions in Chilika Lagoon adversely impacted fishers’ livelihood, this prompted the fishers to formulate various livelihood strategies: coping for subsistence, intensification, extensification, diversification and migration.

Coping for subsistence

“It is difficult to go fishing on an empty stomach. Only when I have arranged firewood for the chullaha (wooden stove) and rice for the pots to cook food, hunger of my family will calm down and I will have the peace of mind to go fishing. In a situation where we lack daily supplies to cook food, I do whatever options are readily available. Who has the time to think about the future?”

– Abhimanyu Jena, Fisher, Berhampur village, July 2007 (translated from Odiya)

Abhimanyu’s statement clarifies that for poor households, a livelihood crisis often impacts the existing support system for subsistence. Taking loans and credit, mortgaging and selling assets, changing food habits, discontinuing children’s education and rearranging personal and professional relationships are sub-strategies the households used.

Intensification

For many fishers, intensification of their fishing activities is the only livelihood strategy available, as they cannot migrate and lack the start-up capital to diversify. Sub-strategies used were altering gear (e.g. catch-intensive nets), abandoning traditional fishing seasons and fishing all year round, catching all sizes, fishing anytime and anywhere, not restricting species or focusing intensively on a species, and intensive shrimp aquaculture.

Photo caption: Chilika fishers. Photo credit: Prateep Kumar Nayak.

Extensification

A sharp decline in fish stock, an enormous loss of customary fishing areas to encroachment, and a lack of access to existing fishing grounds due to ongoing conflicts have forced households to look for alternate fishing areas. At these locations, fishers not only face strong competition from other fishers but they also run the risk of fishing within another village’s territory. Travelling long distances to fish, fishing along key fish movement routes and in deeper parts of the lagoon, fishing beyond the lagoon, catching all available species, sale of freshwater fish and dry fish of all possible species, targeting non-fish species like migratory birds, organizing into groups (e.g. permanent fishing camps), and extensive shrimp farming are strategies used in extensification.

Diversification

Due to a general lack of options and startup finances, livelihood diversification has not been a very successful strategy in Chilika. Even after years of livelihood crisis and a staggering loss of incomes from fishing, most households in the study villages continue to retain fishing either as their primary or the only livelihood occupation. Since these are fishers by caste, who have for generations not done anything else other than fishing, they tend to lack the necessary skills and resources to take up alternate livelihood activities.

Migration

In the study villages, there is not a single evidence of “moving away” (either individually or with family). All cases of migration in Chilika involve migrant work. However, a significant number of those who return from migrant work do not maintain any links with the village fishery institution and the resource base, especially young fishers. Not all households are in a position to afford migration; households with many adult men are in an advantageous position compared to those with fewer adult men because women do not generally migrate. In the absence of men, the households stopped fishing because culturally it was only men who fished. Consequently, women in the households also discontinued their fish processing chores. Thus, migration by men also contributed to the disconnection of those family members who stay behind from their customary Lagoon resources.

Conclusion

The availability of more resources (or capitals) do not necessarily contribute to more robust livelihood strategies or outcomes. The relationship between livelihood shocks and stresses, capitals, institutions and livelihood strategies is circular and not linear. The outcomes of the livelihood crisis and responses from Chilika fishers have resulted in higher levels of their disconnection from the Lagoon and their marginalization. The multiplicity of ways through which fishers in Chilika perceive their livelihood suggest that livelihood in resource-dependent communities, such as Chilika smallscale fisheries, is multidimensional and far more complex and dynamic than often perceived. Further innovations in approaches and tools will help better understand livelihood challenges and make related outcomes sustainable.

Nayak, P. K. (2017). Fisher communities in transition: Understanding change from a livelihood perspective in Chilika Lagoon, India. Maritime Studies, 16:13.

Contact: Prateep Kumar Nayak, School of Environment, Enterprise and Development pnayak@uwaterloo.ca

For more information about the WaterResearch, contact Amy Geddes.