Launched in 2010, the Computer Museum collects, preserves and interprets the history of computing at the University of Waterloo and beyond.

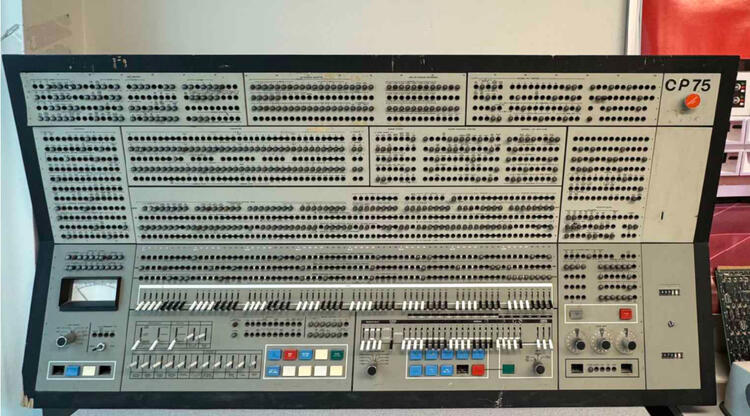

Over its 14-year history, the museum has amassed a vast and varied archive of artifacts, including a panel from the famous IBM 360 Model 75, a slide rule from the 19th century and computers from every era (browse the collection).

The museum offers visitors opportunities to delve deeper into seminal events from Waterloo’s history–like the Oxford Dictionary Project, which led to the launch of tech-giant OpenText–and to try out iconic computers from the past. Imagine playing Space Invaders on an old Commodore SuperPET!

The museum is located in the Davis Centre (DC 1316) and has exhibits in the Davis Centre and Mathematics 3. It also hosts hands-on events called Hardware Days (the next one is March 5) and will be hosting visitors at Reunion 2024 (Saturday, June 1).

E-Ties spoke to the founders of the museum–Lawrence Folland, former Manager of Research Support and Special Projects for the Cheriton School of Computer Science, Scott Campbell (BMath ’99), Systems Design Engineering Lecturer and Director of the Centre for Society, Technology and Values, and Trevor Grove (BMath ’79), former researcher for the Computer Systems Group and adjunct lecturer in the Cheriton School of Computer Science–to find out what inspired them and why it’s so important to preserve our computer heritage.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: Where did the idea for the museum originate and what was your vision?

Trevor Grove:

I remember Scott was collecting oral histories in 2007 about one of the early research groups at Waterloo that I was a member of back in the 70s–the Computer Systems Group (CSG). That’s when I first saw the interest that existed in what had been going on at Waterloo. And it sparked my interest in creating a formal museum. I'm a huge packrat, so I had collected quite a pile of artifacts over the years, great computers from the CSG and other things.

Scott Campbell:

I was a computer science student at Waterloo and then I went to the University of Toronto to study the history of technology. I was hired here in Waterloo in 2007. Around 2010, I got in touch with the Cheriton School of Computer Science and said you should probably have a computer museum because York University has a great one. They told me to talk to Lawrence because he had already approached them about a museum.

Lawrence Folland:

The vision that I had was of a distributed computer museum. I actually called it a doubly linked list. The idea was that you'd have lots of spaces and hallways and places where we could put displays and exhibits. And each exhibit tells you how to get to the next one. Systems Design Engineering was just shutting down a space and they had a collection of items for us (Systems Design has also provided considerable storage space over the years). We took all their items and put up a few display cabinets in the Davis Centre. Several years later, we created a display in the atrium of Mathematics 3 on slide rules. We built that just before the pandemic hit. We got support from the dean for high-quality displays and cabinets and have a very valuable item in it. It’s a slide rule from the 19th century.

The goal was always to become a recognized unit of the university. Shortly before I retired in 2022, the Cheriton School of Computer Science said that, yes, they would make the museum a recognized unit of the School. As a result, we now have a visitor centre in the Davis Centre. We have space for people to work and also to have hands-on exhibits because that’s one of the limitations of cabinets. You can't interact with items. Here in our visitor centre, people can come in and try our old computers.

Keuffel & Esser model 1740 Thacher slide rule

Q: Why is it important to preserve the history of computing at Waterloo, including the physical artifacts that make up your catalogue?

Trevor Grove:

From my perspective, the growth of computer science that happened here at Waterloo occurred in parallel to the growth of the entire computer industry. The work that we were doing was fundamentally important. And there are a lot of stories from our early days that aren't well known. I think it's important for us to try and write down what took place. Look at companies like Dalsa, for example, which Savvas Chamberlain, Profesor Emeritus of Electrical and Computer Engineering, started. It very quietly became the world leader in developing photonic, multi-column, CCD cameras. They were making six-megapixel cameras and selling them to NASA to shoot off into outer space at a time when everybody else had less than one megapixel in their cell phones. This is a story that not many people know. Another example is that incubators are very popular right now. Well, the fact is we've had incubators at Waterloo going back to the 60s. The museum can act to bring those stories together. And the artifacts are something on which we can hang the stories.

Scott Campbell:

The museum needs to fulfill teaching and research purposes, in my opinion, because that's what the University does. The museum has to be embedded within the University’s mission or else it’s not sustainable. As a historian of technology, I do research and teach using the artifacts. This includes a course on the history of computing. I bring in artifacts every single week and the students gather around. They want to touch them. They want to pick them up and feel the weight. Outreach is also a big part of the museum. We've had a couple of alumni days where people come in and show their teenage kids, who are about to apply to Waterloo, the computers they grew up working on. The museum’s pitch is always about outreach, teaching, and research.

Q: What has the community response been to the museum and what artifacts are they most interested in seeing?

Scott Campbell:

The community response every time we've done an event has been amazing. We’ve done a couple of pop-up events with the faculty, including Hardware Days. That’s where we try and get a bunch of old computers up and running and we invite the public to come and see what we're doing. We bring along technology experts, too. Usually, people are interested in seeing the first computer they ever used. I remember when we had an alumni day at the end of May last year, I did a couple of tours here. People were saying “Oh, I remember the IBM 360 Model 75 terminal.” They have very distinct memories of sitting in a lab all night.

Lawrence Folland:

The panel from the IBM 360 Model 75 is obviously very popular. People also like sitting in front of an old Commodore and running a program, like Space Invaders, one of my favourites. We have an IBM Selectric typewriter with a type ball, known as the “golf-ball” head. It was also very popular with visitors. And we’re not just attracting people who have had experience with these computers and are feeling nostalgic. There seems to be a growing interest among young people. We're amazed by the amount of young people who come out and are interested in retro computing.

Q: What are your plans for the future?

Lawrence Folland:

In the short term, our top priority is getting the museum’s main room renovated. We're hoping to install glass windows where you can see into the museum from the hallway of DC. We'd like to have something on the back wall of the museum that emulates the Red Room–make a little vignette with the IBM 360 Model 75 panel mounted and red paint. You could take a picture and it looks like you're working away in the Red Room.

Another thing that interests us would be to develop more programming exhibits. For example, we could create a depiction of what it was like to be a computer science student in the 1970s. It would feature the computers and manuals you used and the games you played. It would show the evolution of teaching computer science at Waterloo. That would be a fascinating long-term project. It's Waterloo-centric and it will attract people of various eras.

We were also talking to one of the technicians who runs the Real-Time Trains Lab. They’re about to renovate their lab. They have enough old hardware that we could set up a sample train and people could run the train interactively. You could push a button and the train goes forward; push another button and the track switches. And there would be a display showing all the real-time data. This would be neat because it's such a storied course and so many alumni will have gone through it. We could answer questions through the exhibit like: why do we teach trains? Why is it so important?

Trevor Grove:

There are lots of hidden stories about technology that came from here, like QNX, which was started by a couple of Waterloo CS graduates (Dan Dodge and Gordon Bell) and eventually acquired by Blackberry. They both got their start in real-time software development in the "trains" lab. QNX and its software is now one of the leading systems used in autonomous vehicles.

Scott Campbell:

From my perspective, history and museums have a function in understanding ourselves. When I teach a history of computing course, I don't teach people how things work. I teach them how to interrogate these artifacts and these stories in order to understand our own relationship to technology today. So it is worth sort of developing these analytical and critical thinking tools that anyone can benefit from. This isn't just for people who want to remember Pong or the first Mario game they played. It's so much more than that. It’s an incredibly rich way of thinking about technology.