By: Darlene Coyle

Before reading the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, I had been vaguely aware of the atrocities committed by the Canadian Government against Aboriginal peoples. I understood that immense wrongs had been done in the age of colonization, but I had not been exposed to the effects these had on Aboriginal culture and individual Aboriginal families. Since these topics are largely absent from the public-school curriculum, I can only assume that most people across Canada are just as naive as I was. However, after reading the report, I strongly believe that the findings should be broadly shared and discussed openly in various settings. Whether an academic setting, political discussion, social media post, or table talk, the goal should be to bring these issues to light in an open and honest manner.

It is a long document, with almost 500 pages of in-depth research of Canada’s history, interviews with residential school survivors and 94 Calls to Action. I don’t expect every Canadian to read it all but my hopes after reading this post is that people agree that a wrong has been done and begin to openly discuss how these cultural injustices can be corrected throughout society.

The report describes reconciliation as “an ongoing individual and collective process and will require commitment from all those affected including First Nations, Inuit, Metis, former Indian Residential School students, their families, communities, religious entities, former school employees, government and the people of Canada. Reconciliation may occur between any of the above groups”. Therefore, reconciliation is not just between Aboriginal peoples and the Canadian government, it is a shift throughout Canadian society in which everyone has a part to play. The way forward will be to learn from the past, acknowledge the lasting harm that has been imposed, atone for the actions committed, and change behaviour in an inclusive and respectful manner.

Canada has yet to accomplish reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples. The damaged trust needs to be mended and apologies must to be made in a meaningful manner. This will not be accomplished by such acts as a public speech by the Prime Minister. This is likely to take generations to accomplish. But the momentum has commenced, and it will, like many issues begin, with getting informed about the issues. To demonstrate how far Canada needs to go to reconcile the relationship with Aboriginal peoples I will briefly discuss experts from the report, including statements from residential school survivors about their personal experiences.

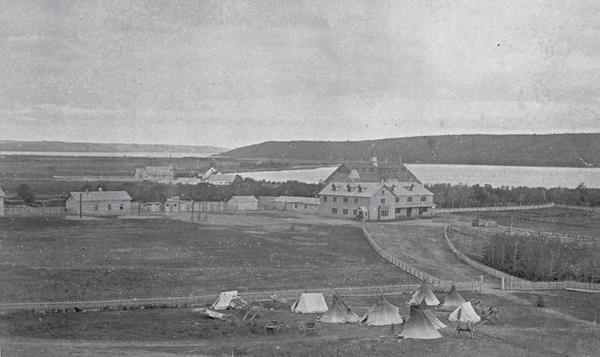

Canadian residential schools are often described as a form of cultural genocide, the destruction of structures and practices that allow a group to continue as a group, since residential schools were formulated based on the effort to eliminate Aboriginal people as distinct peoples and to assimilate them into Canadian, colonial society. This analysis is reinforced by Sir John A. Macdonald’s statement to the House of Commons in 1883 justifying the government’s residential school policy, claiming Aboriginal children needed to be taken away from their parents, who were thought of as “savages”, in order to “acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men”. It was thought that if children were taught while continuing the familiarity of their families and culture, he “is simply a savage who can read and write”.

Now imagine this, you are a small child, maybe five- or six-years old, taken from your parents and put on a truck that takes you to the school where you will be stripped of you belongings, separated from your siblings, and thrust into a world dominated by fear, loneliness, and lack of affection. The school is poorly maintained, discipline is harsh, your native language is forbidden, your entire culture is criticized and supressed by the school run by missionaries, and you remain there until your education is complete. You are probably thinking what Marthe Basile-Coocoo recounted about her first day at Pointe Bleue, Quebec, school; “It was something like a grey day, it was a day without sunshine. It was, it was the impression that I had, that I was only six years old, then, well, the nuns separated us, my brothers, and then my uncles, then I no longer understood. Then that, that was a period there, of suffering, nights of crying, we all gathered in a corner, meaning that we came together, and there we cried. Our nights were like that.”

The report recounts the conditions of these schools in great detail, hearing from more than 6,000 witnesses, most of whom are residential school survivors accounting their experiences. This includes passages from public Sharing Circles such as Simone’s, an Inuk Survivor from Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut who spoke to honour the memory of his relatives who had passed, “I’m here for my parents—‘Did you miss me when I went away?’ ‘Did you cry for me?’—and I’m here for my brother, who was a victim, and my niece at the age of five who suffered a head injury and never came home, and her parents never had closure. To this day, they have not found the grave in Winnipeg. And I’m here for them first, and that’s why I’m making a public statement”.

For those that experienced residential schools, reconciliation is about healing themselves, communities and nations in ways that rejuvenate individuals and their Indigenous culture, languages, spirituality, laws and governance systems. For governments, it will be about fostering a respectful relationship by dismantling a century long prejudice governance system. For churches, a long-term commitment to right the wrong of church-led residential school campaigns that respects Indigenous spirituality. And for everyone else, it will be through open dialogue and support for inclusivity.

After reading about the deliberate intent to eliminate Aboriginal culture and identity, it is no wonder Aboriginal peoples today are so hesitant to accept collaborations and discussions with the government. It is this long history of betrayal and suffering that has driven these feelings of mistrust and it sometimes feels as if the federal government has forgotten the lasting impacts of these events.

Fast forward to present day, and one can still identify areas to which Aboriginal peoples continue to be cast aside in the decision-making process for projects that directly effect their livelihood. Yes, I am talking about the failure to meaningfully consult effected Indigenous groups on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. A project that is argued by some (mainly stakeholders of the oil industry) as crucial to the Canadian crude oil industry. However, even if you agree that this statement is valid, is it so at the expense of environmental and cultural destruction? Even with the potential to contaminate freshwater sources in the face of an Indigenous water crisis? I would not agree.

The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada provided an opportunity for residential school survivors and their families to share their experiences and raise awareness of Canada’s hidden past. The purpose of the document is to educate Canadians on the legacy of colonialism and residential schools, as well as the need for collective healing towards reconciliation.