The resilience of communities to environmental change is increasingly a priority as cumulative impacts of changes in climate are becoming increasingly visible. The use of monitoring programs that inform policy and decision-making and increase capacity to implement relevant strategies is key such that decision makers, managers, and local communities better understand what changes are likely to occur, the implications of these changes, and the effectiveness of management measures.

The Muskoka River Watershed (MRW) consists of over 2000 lakes connected by the Muskoka River, and covers about 4660 km2 in Ontario, Canada. Although most watersheds in Ontario are managed by Conservation Authorities, the Muskoka River Watershed is not. Instead, the watershed has the non-regulatory Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC), a volunteer group of government representatives, scientists, and citizens, tasked with understanding the health of the watershed and reporting this information to residents, managers and decision-makers. Monitoring in the MRW varied from year to year. Information from the monitoring program was published in plain language Watershed Report Cards which were accessible on-line approximately every four years.

Using the MRW as a case study, the research identified opportunities for strengthening watershed-scale monitoring approaches and improving communication with stakeholders, for example through “state of the watershed” reporting, to enhance the climate-resilience of communities and ecosystems.

Methodology

A three-step study design was used:

- Establish a knowledge baseline of what has been done and what is currently being done to address climate change and to consider cumulative effects in Canadian monitoring and management programs;

- Discuss and confirm the baseline to ensure perspectives that emerged were inclusive of multiple stakeholders;

- Hold an exploratory workshop to disseminate recommendations to key stakeholders and engage in discussion regarding implementation of a watershed monitoring system, including indicator selection.

Outcomes

A review of literature concluded that a cumulative effects assessment and monitoring (CEAM) program is well-suited to the goal of strengthening MWC’s current monitoring efforts. CEAM seeks to not only react to existing concerns, but to prevent future ones, a key tenet of climate resilience. Despite rapidly growing interest to consider cumulative effects (CE) in watershed and water monitoring, CE is not yet broadly considered because of three main challenges: i) concepts have developed slowly and are jargon rich, ii) there is a lack of standardization in implementation, and iii) legislative mandates and guidelines lag behind and need improvement.

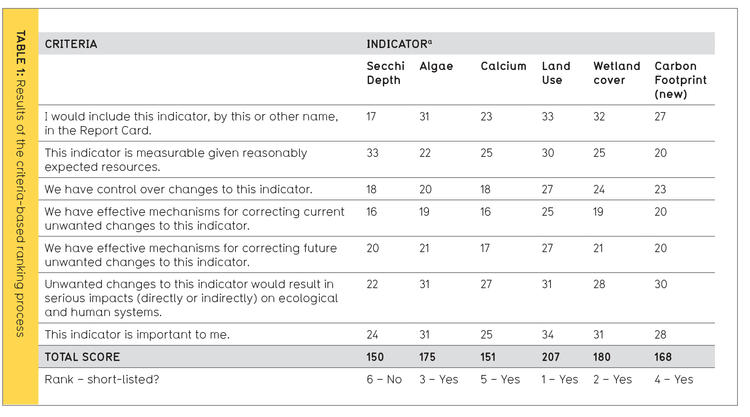

A new criteria-based ranking process for indicator prioritization was tested. The process addresses potential bias in situations where indicators are chosen without the participation of representative watershed stakeholders. Using broad ecological, socio-political and economic criteria agreed-upon by a diverse group of stakeholders was thought to be more likely to result in a list of indicators that responds to multiple needs and addresses multiple issues and stressors than continuing without assessment criteria. Table 1 shows results of the ranking process test. The process produced a different set of indicators than had been used before and, most importantly, a process of consultation and prioritization that is both replicable and well documented for future reference should conditions change.

Table 1: Results of the criteria-based ranking process.

NOTES: Scores are the sum of individual participants’ scores for each criterion.

Adopting a CEAM program in MRW would require improvements in the way data are prioritized, collected, and stored. The review revealed monitoring inconsistencies in what was measured from year to year, affecting the usability of data in analyses. Data challenges, including limited capacity to address all issues across the watershed at all times, unstandardized data collection methods, uncertain access to individually held data, and the high turnover of MWC personnel, were identified.

A central meta-database will improve accessibility and transparency of the available data sets. In addition, a meta-database can be used as a tool to enhance continuity between successive staff members so as not to reinvent or diverge from the current monitoring program every time staff composition changes. MWC is the most logical host of a meta-database. However, taking on this initiative would require administrative capacity and funding, as well as buy-in from regional monitoring bodies and regulatory bodies responsible for local watershed management.

The 2018 Watershed Report Card, MWC’s first Report Card since this study was completed, demonstrates several changes that refl ect the review and recommendations presented in this paper. Fewer indicators are reported upon, and cumulative impacts are discussed with the community, although not necessarily measured through monitoring. The 2018 Report Card also includes more accessible formats, such as infographics and story maps.

Conclusions

Influencing behavioural change using data from watershed monitoring requires a coherent storyline with consistent communication of what was measured. In the case study, easily understood units that are consistent, and fewer indicators being communicated in both the Report Cards and the background reports, would make the shared information much more effective. Plain language communication of specialized knowledge is also crucial. A common understanding of the story being told, and a clear vision regarding how the data will be used, are important precursors to the design of successful watershed monitoring and reporting programs. Understanding the end-users is critical to ensuring they are reached. As a result of this study, MWC made significant progress in its Watershed Report Cards program, even though the impacts of these changes are still being measured. In addition, MWC continues to review its monitoring program and whether/how to incorporate cumulative effects.

The study guided future monitoring and reporting in the MRW. Two main recommendations were presented to strengthen watershed monitoring: i) a CEAM program should be developed and implemented, and ii) an easy-to-use metadatabase should be created. In terms of reporting watershed health, it was stressed that developing and implementing an ongoing communications strategy must ensure consistency and continuity between Watershed Report Cards so community members can infer trends and implications, and decision-makers will be better equipped to address potential risks from climate change and other stressors, increasing the resilience of watershed communities.

Ho, E., Eger, S., Courtenay, S.C. (2018). Assessing current monitoring indicators and reporting for cumulative effects integration: A case study in Muskoka, Ontario, Canada. Ecological Indicators. 95, 862-876.

Contact: Elaine Ho, School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability

For more information about WaterResearch, contact Julie Grant.