Introduction

The land and sea are inherently connected via multiple, complex social-ecological interactions that are important components of local ecologies and major factors influencing people’s livelihoods and wellbeing. These land-sea connections have been grouped into three categories in previous research:

- Land-sea processes: natural material and physical flows occurring within land-sea ecological processes (e.g. freshwater rivers carrying sediments and nutrients to coastal areas).

- Cross-system threats: a biophysical or environmental change (human-induced or otherwise) in one sub-system (i.e. the land or the sea) that has implications for another (e.g. agrichemicals, if used improperly or irresponsibly, can make their way into coastal areas).

- Management and policy decisions: having an overarching influence on both land-sea processes and cross-system threats, these decisions can have significant effects on human influences and vice versa (e.g. designation of conservation areas or enacting land-use restrictions).

It is the latter category – the influence of policy and management decisions and the social processes and values that drive those decisions – which brings us into the realm of governance. We define governance as the processes and institutions (e.g. cultural norms, rules) through which societies make decisions that affect the environment (in this case, the land-sea interface).

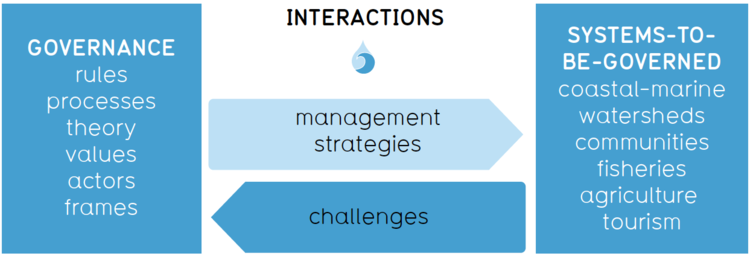

The relationship between governance, systems-to-be-governed, and interactions between the two can be shown as a framework (Figure 1). Within this framework, governance represents the structures (e.g. rules, networks), decision-making processes, actors, and ideas that shape what management strategies, if any, are chosen and implemented. Additionally, land-sea systems pose significant social and biophysical challenges for governance.

Figure 1. Relationship between governance and land-sea systems.

Methodology

Governance across the land-sea interface is an emerging challenge. The propensity for, and intensity of, social-ecological interactions across this interface (e.g. eutrophication, sedimentation) are being exacerbated by cross-system threats (e.g. climate change). To address a gap in the literature, we conducted a comprehensive literature review that focuses on the governance of the land-sea interface. We systematically identified peer-reviewed, contemporary scientific literature related to governance and land-sea connections. We then screened the available literature using specific criteria, and identified 151 papers to include in a three-phase quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Outcomes

The current body of literature consists mainly of review papers, with articles appearing primarily in interdisciplinary journals. Most articles do not define governance, although concepts of governance appear in the literature. These include governance as context (the framework of rules and regulations that enable and constrain management; 37% of all papers), praxis (contains the framework of rules, but also considers the process and people involved in governing; 52% of all papers), and theory (a set of propositions, ideas and hypotheses to be tested, explored and updated; 4% of all papers). The remainder of the papers (11%) did not use either of these concepts of governance, or did not provide enough information to make an adequate judgement.

Three types of management approaches are predominant in the literature:

- Ecosystem-based management (52% of all papers): emerged from the natural sciences – usually requires integration across jurisdictions, sectors and system components; however, it additionally implies a focus on sustainability, exercising precaution, and adaptive improvement to increase effectiveness.

- Integrated management (35% of all papers): emerged from planning and other social science disciplines – deliberately considers various elements in the approach, including jurisdictional fragmentation and competing interests.

- Land-sea conservation planning (5% of all papers): related to but distinct from the other two approaches – considers additional elements including complementarity between selected areas, least-cost solutions to achieving objectives, and transparent and repeatable methods for designing configurations of conservation areas.

The remainder of the papers (8%; n=12) either did not provide enough information to make a clear classification or they referred to multiple management approaches.

Boundaries for management and governance of land-sea interactions are difficult to establish and therefore one of the predominant challenges identified. The appropriate spatial scale that encompasses the relevant social and ecological systems do not always align with pre-existing boundaries (e.g. regulatory jurisdictions). Climate change adds urgency to the need to determine appropriate boundaries, but also an extra dimension to this key challenge. As climate change modifies important land-sea social-ecological processes, the potential need for transboundary or transnational initiatives becomes greater. For example, the oxygen-deprived "dead zones" in the Gulf of Mexico are caused, in part, by agricultural intensification and subsequent nutrient runoff occurring far inland. These areas, in addition to being separated by space, are separated by pre-existing boundaries including jurisdictional, sectoral and livelihood, and possibly social.

Another key challenge is considering spatial, temporal, and functional dimensions to determine appropriate social and ecological scales for action. Interactions between the land and sea operate at many different scales, and governance must be able to match these scales. For example, governing the land-sea interface must consider the balance between scaling up to address system-level problems (e.g. ocean patterns and biological connections), while simultaneously scaling down to empower social actors (e.g. fishing or farming organizations).

A third and final key challenge is to develop suitable processes for accessing and engaging with diverse sources and types of knowledge, since a holistic understanding of the behaviour of the system is important for successful integrated management. For example, some governance systems focus entirely on certain forms of knowledge (e.g. scientific knowledge) of only parts of the system (e.g. ecosystems). We need governance that can draw in knowledge from diverse sources and apply it to the most pressing challenges.

Insights into the predominant factors contributing to governance effectiveness include:

- Science-Policy Integration: use of scientific knowledge when making policy is an important element in effective governance. A key ingredient of successful science-policy integration appears to be the focus on interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary science, which facilitates access to diverse forms of knowledge through a two-way dialogue between researchers, policy-makers, and other stakeholders.

- Functional Fit: accounting for the characteristics, processes and dynamics of the ecosystem was a commonly cited element of effective governance in the literature. Functional fit usually involves governing at land-sea ecosystem scales or drawing management boundaries to encompass relevant ecological processes.

Conclusions

The results of the literature review demonstrate the need to develop a richer conceptual framework of governance across the land-sea interface. In the context of rapid social and environmental change, this framework is crucial to promoting sustainability.

Governance in the context of land-sea interactions must account for the direct social and ecological linkages and feedbacks, including consideration of different livelihood activities and environmental settings. There are important gaps in the current literature. Ongoing conceptual development in the areas of collaboration, networks, fit and social-ecological systems are considered relevant sources of innovation to foster meaningful and beneficial governance across the land-sea interface.

Pittman, J.and D. Armitage (2016). Governance across the land-sea interface: A systematic review. Environmental Science & Policy 64, 9-17.

Contact: Jeremy Pittman, School of Planning; Derek Armitage, School of Environment Resources and Sustainability; Prateep Nayak, School of Environment, Enterprise and Sustainability

For more information about the Water Institute, contact Amy Geddes.