Waters of Knowing

QES Ghana Field School Blog by Jordan Wilton, June 2025

My name is Jordan Wilton, and I am an undergraduate student in the Environment, Resources, and Sustainability program. I am currently in Cape Coast, Ghana, where I am spending two months studying environmental issues through the Queen Elizabeth Scholars program. We have just completed our third week of the Field School, which has focused on the complex drivers and impacts of water insecurity.

Defined as “the inability to benefit from adequate, reliable, and safe water for health and wellbeing” (Jepson, 2017), water insecurity is more than scarcity and infrastructure; it is interconnected with gender, education, health, climate resilience, and livelihoods. This week, our academic sessions explored these intersections through the lens of WaSH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) and gendered health inequities. In a guest lecture, health geographer Dr. Abraham Nunbogu framed these perspectives in the context of “place” and Krieger 2005’s concept of “embodiment”, where “our bodies tell the stories of our living conditions, reminding us that people are connected, and so is our health” (Nunbogu, 2025).

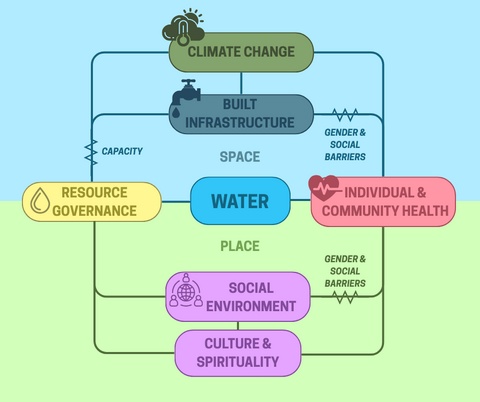

Systems Mapping Activity in ENVS 476C/SCI 300 by Jordan Wilton

Through lectures, site visits, and everyday conversations, I was challenged to think of water beyond just a material resource. Taking a more holistic approach helped me see that environmental issues are shaped by power, place, and inequities in resources and health. Conservation and resource management can take many forms, drawing on diverse ways of knowing that are rooted in real lives and lived experiences, like those we engaged with during our field visits this week.

WaSH and Gender-based Violence (GBV)

In a presentation by my peers Emily and Sophia, we examined water insecurity through the lens of pregnant and postpartum women in Kenya, who face disproportionate burdens due to gendered expectations around water acquisition (Collins et al., 2019). We also explored how limited access can expose women to gender-based violence (GBV), where women’s movement through space to access water often exposes them to risk and is shaped by rooted power dynamics and cultural expectations (Nunbogu & Elliott, 2022).

As a student passionate about menstrual health and education, I have learned how WaSH infrastructure shapes girls’ ability to manage menstruation safely and attend and participate at school (Nunbogu & Elliot, 2022). In Cape Coast, I spoke with a woman who described the lived realities of these challenges within Central Region, where many young girls lack the basic resources, education, and social support needed to navigate menstruation with dignity. This made our “privilege walk” learning activity especially meaningful. I was assigned the role of a menstruating girl in a rural area, where I stepped through a series of questions on access to WaSH. This activity allowed me to reflect on how social, gender, and spatial inequalities shape who has access to safe water and sanitation.

Sekyere Hemang Headwaters Treatment Plant

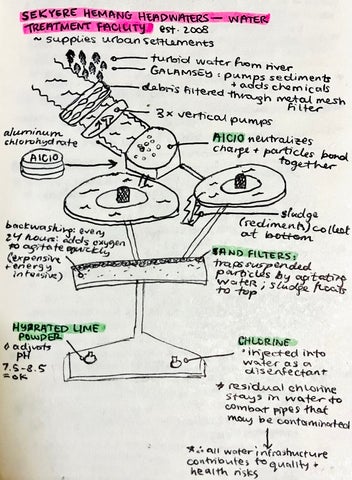

During our visit to the Sekyere Hemang Headwaters Water Treatment Facility, we gained a technical understanding of how river water is processed. This plant is challenged with highly turbid water, often affected by galamsey (illegal mining) activities, and filters it through a multistep system. To meet water quality and safety requirements, water undergoes chemical separation, sediment filtration, pH adjustment, and chlorination. Despite this detailed infrastructure, we learned that water systems are energy-intensive and vulnerable to contamination, particularly through the pipe system in which water travels to communities. This is only one part of the broader picture: many communities remain under ‘boil water advisories' and rely directly on untreated surface water sources, highlighting the uneven realities of water access and safety.

Sekyere Hemang Headwaters Treatment Plant Diagram by Jordan Wilton

Water and Climate Change: Anlo Beach Community

Each Wednesday at the University of Cape Coast, we spend the day volunteering with local environmental NGOs as part of our community placements. I have been working with PHE Link, an emerging environmental health organization led by Madame Violet Ahenkorah. This past Wednesday, I created educational video content that discusses the layered challenges faced by a coastal community along Anlo Beach. Along the coast, residents are experiencing compounding impacts of sea-level rise and plastic pollution which are threatening local water sources, increasing exposure to water-borne diseases, and disrupting livelihoods. For Anlo Beach, saline intrusion into groundwater has affected their water security by making it more difficult to acquire safe drinking water. Addressing these interconnected issues requires balancing and bridging our academic knowledge with community knowledge. Working with PHE Link has emphasized the importance of meeting people where they are; reminding us that meaningful solutions must be rooted in context and shaped by lived experience.

Traditional Knowledge: Nsofa Forest, Eshirow Community

Our class had the rare privilege of being welcomed into the Eshirow Community, where we spoke with the Chief, walked through the sacred Nsofa Forest, and learned how traditional knowledge informs environmental stewardship. The forest is protected not only for its ecological value, but woven into the community’s social, physical, and spiritual wellbeing. As described by Esia-Donkoh (2011), groves like Nsofa are preserved for “totem (of clans and families) or sacred (for rituals and medicine)” purposes. Through collaborative governance between the Chief (traditional leader) and municipal authorities, the forest has gained formal protection against illegal cutting, while also preserving ancestral knowledge.

We learned about the healing properties of endemic plants used to treat toxin exposure, digestive issues, and waist pain, and how this medicinal knowledge is passed down through generations—shared orally, practiced during ceremonies, and when asked by younger community members. It reminded me that as climate change disrupts ecosystems, it also disrupts cultural memory.

Professor Kobina Esia-Donkoh, who accompanied us on this field experience, brought a unique perspective through his experience with the Eshirow Community and his framing of trilogic knowledge—an approach that bridges material, social, and spiritual science to foster holistic understanding (Esia-Donkoh, 2011). In Nsofa Forest, Professor Kobina shared how traditional ecological knowledge is rooted in an ecocentric worldview, where “every resource has life” and inherent value. This visit reminded me that environmental stewardship is not only about protecting ecosystems, but also protecting the relationships, stories, and knowledges that live within them. In the context of water governance, this experience has shown me how conservation management can look differently across contexts, guided by how stakeholders view and value water.

Going Forward: Invisible Geographies

This week has shown me that water is not just a resource, but a relational thread connecting systems of health, infrastructure, gender, governance, and culture. The diagram I developed below visualizes this complexity by mapping how water is positioned at the intersection of space, the physical systems of built infrastructure, climate vulnerability, and institutional capacity, and place, where social environments, cultural beliefs, and lived realities shape everyday experiences of access.

Diagram of water across space and place

As we moved between lectures, field visits, and community engagement, I came to understand what Krieger 2005 meant by “our bodies tell the stories of our living conditions.” Invisible geographies emerged in our conversations with community members, in understanding gendered inequities in WaSH, and in the traditional knowledge shared in sacred groves. These stories reflect where people live, what they can access, and how WaSH is a fundamental human right as it is interconnected with health, wealth, and dignity (Mariwah, 2025).

Going forward, I am thinking about how we can better include interdisciplinary perspectives to go beyond the visible parts of a story. The geography of water is not just physical; it is also emotional, spiritual, political, and it lives in the spaces between.

References

Collins, S. M., Mbullo Owuor, P., Miller, J. D., Boateng, G. O., Wekesa, P., Onono, M., & Young, S. L. (2019). “I know how stressful it is to lack water!” Exploring the lived experiences of household water insecurity among pregnant and postpartum women in western Kenya. Global Public Health, 14(5), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2018.1521861

Esia-Donkoh, K. (2011). Beyond science: Traditional concept of preservation and biodiversity in Ghana: Focus on two traditional areas in Central Region. Oguaa Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 141–169. Retrieved from https://journal.ucc.edu.gh/index.php/ojoss/article/view/594

Jepson, W. E., Wutich, A., Colllins, S. M., Boateng, G. O., & Young, S. L. (2017). Progress in household water insecurity metrics: a cross‐disciplinary approach. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Water, 4(3), e1214-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1214

Krieger, N. (2005). Embodiment: a conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979), 59(5), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.024562

Mariwah, Simon. (2025, June 24). Wash Prioritization for Sustainable Development in Ghana. University of Cape Coast. [PowerPoint Presentation].

Nunbogu, A.M. (2025, June 24). Invisible Geographies of WaSH Vulnerability: Gendered Health Inequalities across Place and Scale. United Nations University. [PowerPoint Presentation].

Nunbogu, A. M., & Elliott, S. J. (2022). Characterizing gender-based violence in the context of water, sanitation, and hygiene: A scoping review of evidence in low- and middle-income countries. Water Security, 15, Article 100113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2022.100113