Waterloo Magazine

Waterloo Magazine 2025: Game Changers

Explore alumni, researchers and students who are redefining their disciplines — the game changers helping us to create a better future for humanity and our planet

Reinventing tradition

Since 1970, the University of Waterloo has delivered alumni stories that engage, inspire and connect our community – first through the Alumni Courier, and since 1989, the Waterloo Magazine.

Looking ahead, we are making way for exciting new opportunities, which means this will be our last issue of Waterloo Magazine.

We remain committed to sharing stories about Waterloo’s community of more than 260,000 graduates as they improve life in their community and beyond.

Unlocking the mysteries of the universe

Using a global network of telescopes, Dr. Avery Broderick and a team of researchers are bringing black holes into view for the very first time

Revolutionizing baseball training with AI-simulated pitchers

Joshua Pope (BASc ’19) and Rowan Ferrabee (BASc ’19) explain how their unique pitching machine is changing major league baseball

Changing the way people explore Africa

Eyitemi Popo (MDEI ’16) discusses her role as a founder and shares her vision for transformation and collective growth in a women-driven economy

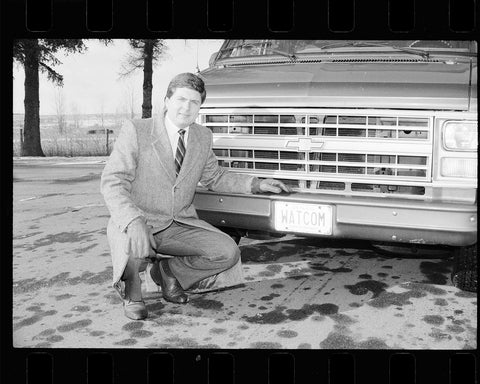

How WATCOM transformed computing

Dr. Don Cowan (MSc ’61, PhD ’65) and Ian McPhee (BMath ’73, MMath ’79, DMath ’11) reflect on the rise of Waterloo’s first software spin-off

Co-op’s coming of age

Since 1958, Waterloo’s co-operative education program has been launching successful careers

The Waterloo Magazine turns its final page

Honouring a rich legacy, and looking ahead to new ways of celebrating the bold spirit of the Waterloo community

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Strategies for success: Building a strong, supportive network →

Jennifer Lee (BA ’00), vice-chair at Deloitte Canada, shares six practical tips to build impactful connections

Champions of change →

Meet six world-class researchers, alumni and students who are applying boundary-breaking approaches to redefine sports, recreation and tourism

Flourishing through adversity →

Dr. Nel Wieman (BSc ’88, MSc ’91) discovers her passion for helping people and becomes Canada’s first female Indigenous psychiatrist

When support comes full circle →

Disney Lam (BMath ’14) honours her father’s legacy by encouraging the next generation of female software engineers

Reshaping bone repair with 3D printing →

Waterloo researchers are developing 3D-printed bone grafts that promise safer, more effective treatments for patients

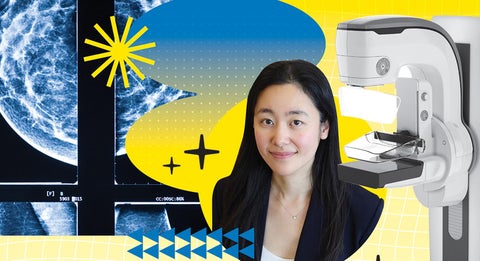

Statistical insights that can save lives →

Shu (Joy) Jiang (PhD ’18) is designing a modelling tool to help patients better understand their breast cancer risk

CLASS NOTES

Dr. Steven Mintz (OD ’73) retired after almost 51 years of practice, including 45 years as partner in RMC Optometric Group in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Vince Woo (BCS ’07) and the team at NASA-JPL launched the Europa Clipper satellite on a five-and-a-half-year journey to Jupiter.

The first satellite location of Green Care Farms, founded by Rebekah Churchyard (BA ’13, BSW ’14), was established: Meaford Green Care Farms. Churchyard also won a Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest Rogers Women of the Year Award.

Isabel Hilgendag (MSc ’22) hiked the 4,265 km Pacific Crest Trail from Mexico to Canada over five months, becoming one of fewer than 10,000 people to complete the entire trek.

In memoriam

Commemorating alumni who have died

Talk of the campus

News and updates from around our campus

ARCHIVES

Fall 2023

PDF Edition

Spring 2023

PDF Edition

Fall 2022

PDF Edition

Update your contact information →

This is our final issue of the Waterloo Magazine. Share your email to get stories, updates and news to your inbox.