Contact

Contact

Kelly Skinner, School of Public Health Sciences

Kelly Skinner, School of Public Health Sciences

Brian Laird, School of Public Health Sciences

Brian Laird, School of Public Health Sciences

Mylène Ratelle, School of Public Health Sciences

Mylène Ratelle, School of Public Health Sciences

Introduction

Water security remains a challenge for many Indigenous communities in Canada, especially for remote and northern communities. A history of unreliable drinking water systems has contributed to the perception of low-quality water in these communities. Historical industrial activity has left many communities with polluted sites, while more recently resource development, long-range contaminant transport and climate change are increasing community concerns. Water insecurity in these remote communities can be associated with indirect adverse health effects, such as obesity, diabetes or gastritis, as well as economic, social, and cultural impacts.

The relationship between water insecurity, unreliable access to safe water and the perceived health issues from water of northern populations creates a complex situation and challenges the ability to promote wellness from water consumption. Through a larger environmental health study in the Northwest Territories and Yukon, Canada, community members expressed concerns regarding water safety and contaminant exposure which resulted in a water security research component being integrated into the larger project. The primary objectives of the component were to: i) characterize the consumption of water and beverages prepared with water, and ii) identify perceptions related to water consumption in Indigenous communities to support public health efforts to make water a drink of choice.

Methodology

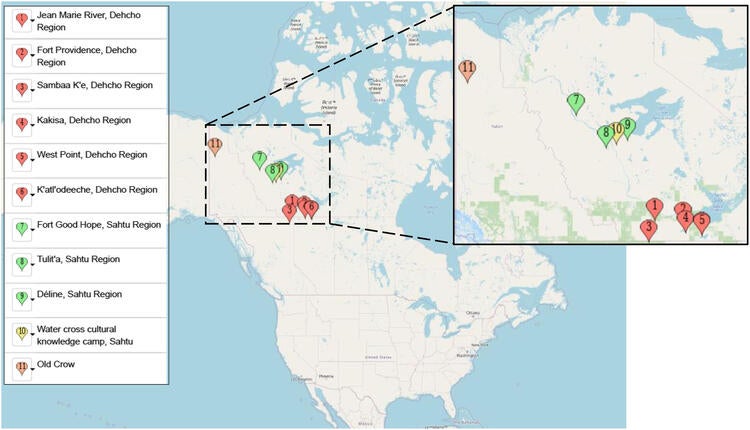

The study data in this paper are from a longer-term, community-led initiative conducted from 2016 to 2019 in the Dehcho region (Jean Marie River First Nation, K’atl’odeeche, West Point First Nation, Deh Gah Gotie First Nation, Ka’a’gee Tu First Nation, Sambaa K’e First Nation) and Sahtú region (Tulít’a Got′ı˛nę, Délı˛nę Got′ı˛nę, K’áhsho Got’ı˛nę) of the Northwest Territories and one community (Old Crow) in the Yukon, Canada (Figure 1).

Indigenous collaborators initiated the project and participated in proposal writing, research design and data collection. Findings were shared with collaborators and leadership from Indigenous organizations before publication.

Figure 1: Participating communities from the Yukon and the Northwest Territories

A mixed methods approach was used to collect data during cold weather months from November to March. Specific methods included food surveys, a health message awareness and perception survey, a contaminant exposure survey, terminology workshops and human biomonitoring samples. Participant recruitment was based on a random selection process for every community with over 100 residents in conjunction with walk-in recruitment. A total of 199 individuals took part in the 24-hour dietary recall, and 150 individuals took part in the Health Messages Survey. A focus group was also conducted with Elders during an on-the-land cross-cultural Water Knowledge Camp in 2019 in the Sahtú region to provide additional context.

Data were compiled and descriptive frequencies (n, %, quantity) were calculated using Microsoft Excel, while analytical statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS. Differences in responses were assessed using the χ2 statistic. Mann–Whitney tests were used to assess associations between risk perception and the quantity of water consumed. Focus group data were analyzed using dialogic/performance narrative analysis which allows for the interpretation of text that has a storied form.

Outcomes

In the Northwest Territories, the consumption of water-based beverages was 0.9 L/day on average in winter, mainly consisting of tea and coffee. Of the 81 per cent of respondents who reported consuming water-based beverages in the previous 24 hours, 33 per cent drank more bottled water than tap water. About two per cent of respondents consumed water from the land. Women tended to drink more bottled water, while men were likely to drink water from the land or water brewed as coffee and tea. Of the respondents, 67 per cent added sugar to their water-based beverages impacting the quality of diets and the importance of promoting plain drinking water (Table 1).

|

Men (n = 80) |

Women (n = 82) |

Both sexes (n = 162) |

|

|

Participants, % |

49.4 |

50.6 |

100 |

|

Drank any water-based beverage, % |

80.0 |

82.9 |

81.5 |

|

Sources of water |

|||

|

Drank at least 1.5 L of water (all sources of water), % |

18.8 |

19.5 |

19.1 |

|

Drank water from the land, % |

3.8 |

1.2 |

2.5 |

|

Drank more bottled water than tap water, % |

23.8 |

42.7 |

33.3 |

|

Drank more tea/coffee than water, % |

45.0 |

34.1 |

39.5 |

|

Quantity of consumed water – mean |

|||

|

Total water sources below, L |

1.145 |

1.189 |

1.168 |

|

Tap water, L |

0.199 |

0.276 |

0.239 |

|

Bottled water, L |

0.238 |

0.417 |

0.330 |

|

Untreated water from the land, L |

0.021 |

0.004 |

0.012 |

|

Tea/coffee, L |

0.707 |

0.496 |

0.598 |

|

Diet |

|||

|

Added sugar to their water-based beverage, % |

59.0 |

75.5 |

66.8 |

|

Average of added sugar in the water-based beverage, g |

94.7 |

105.5 |

99.8 |

|

Average of added sugar in the water-based beverage as a percentage of total added sugar for the day, % |

52.9 |

51.6 |

52.3 |

Table 1. Water consumption and diet information, Northwest Territories

In the Yukon, women reported higher rates of lake/river water as a main source of water than men and fewer women reported drinking bottled water as a main source of water (Table 2). Tap water was the main source of drinking water for both Northwest Territories and Yukon respondents (67% and 87%, respectively) demonstrating the importance of water treatment facilities and associated infrastructure in these communities.

|

Statements |

Men (n = 27) |

Women (n = 36) |

Both sexes (n = 63) |

|

Participants, % |

42.9 |

57.1 |

100 |

|

In the last year, did you drink untreated water from the lake, the river, the snow, or the ice |

|||

|

Rarely or sometimes, % |

48.1 |

47.2 |

47.6 |

|

Often, % |

22.2 |

16.7 |

17.4 |

|

In the last year, was your main source of drinking water |

|||

|

Bottled water, % |

11.1 |

2.8 |

6.3 |

|

Tap water, % |

85.2 |

88.9 |

87.3 |

|

Lake/river, % |

3.7 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

Table 2. Water sources in the Yukon

While existing data in each of the participating communities indicated that the tap water was safe to drink, the study confirmed that communities had concerns related to the safety of their water. Chlorine and metals were identified as contaminants of primary concern and during engagement activities participants frequently shared negative comments related to the taste and odour of tap water (Table 3). It was noted that while historical considerations such as government mistrust and legacy contamination likely influenced perceptions of water safety, the communities had limited knowledge on the extent to which human activities in the region were affecting water quality.

|

Statements |

NWT (n = 87) |

Yukon (n = 63) |

NWT + Yukon (n = 150) |

|

Percentage of respondents |

58.0 |

42.0 |

100 |

|

Percentage of respondents who have concerns about chlorine in water |

62.1 |

61.9 |

62.0 |

|

Percentage of respondents who have concerns about metals or heavy metals (mercury, lead, uranium or other) |

87.4 |

74.6 |

82.0 |

|

Percentage of respondents who indicated that water was a source of other contaminants that may impact their overall burden of contaminant exposure. |

5.7 |

0.0 |

3.3 |

Table 3. Results from the Health Messages Survey

During the focus group, Elders noted that people preferred the taste of water from where they were from, both geographically and source-specific. They reminded the researchers that Indigenous knowledge informs people where it is safe to drink the water from lakes and rivers. Good water, or ‘living water’, is water that flows, moves and is indirectly oxygenated, whereas dead water, which is not safe to drink, is stagnant water where algae can develop more easily.

Similar to survey participants, Elders expressed concerns about chlorine in tap water, in particular its smell and taste, which limited the amount consumed. Traditionally, parents often taught their children not to drink water, but to boil it for use in broth (e.g., fish broth) and tea. Elders noted confusion with current advice given by doctors who recommend drinking more water and recommended that health authorities, in consultation with community members, inform people on where water is safe to drink, how best to clean water tanks, and the environmental challenges of bottled water.

Conclusions

The importance of water security to the wellness of Canada’s remote northern communities is multi-faceted. Water fulfills essential needs such as drinking and cooking, while ice and waterbodies are used for transport and access to traditional country foods. Importantly, water has spiritual and cultural dimensions and is linked with a sense of identity and place.

Frequent water contamination, low trust in crown governments, unreliable water delivery services, taste and odour issues, and insufficient water quantity have contributed to water insecurity in Indigenous communities and resulted in disproportionate water-related challenges in northern Canada. The study showed that chlorine smell and taste was the main limiting factor to the consumption of tap water and that Indigenous knowledge might impact both the perception and consumption of water.

A stronger collaboration with Indigenous partners is required to effectively promote treated tap water as people’s drink of choice. Regardless of access to safe tap water, Indigenous communities will continue to consume water from untreated sources for cultural and spiritual practices that date back to precolonial times. An increased protection of source water can improve drinking water quality, while also supporting reconnection with the land for Indigenous people in Canada. Health risk assessments should consider the importance of untreated water to northern Indigenous communities.

Ratelle, M., Spring, A., Laird, B. D., Andrew, L., Simmons, D., Scully, A., Skinner, K. (2022). Drinking water perception and consumption in Canadian subarctic Indigenous communities and the importance for public health. FACETS. doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0094

For more information about WaterResearch, contact Julie Grant.