Truth and reconciliation actions that emerged while exploring co-reclamation of oil sand-degraded homelands

Truth and reconciliation actions that emerged while exploring co-reclamation of the oil sands-degraded Fort McKay First Nation homelands

The sustainability of a landscape and its host community post-mining depends on careful and effective mine closure and reclamation planning and monitoring. Such activities have the potential to support the renewal of cultural landscapes and to re-establish traditional land use1 capability on reclaimed lands for affected Indigenous communities to exercise Indigenous and Treaty Rights within their traditional territories.

Traditional land use refers to established practices by Indigenous Peoples through generations of custom, belief, knowledge, and experience that are handed down to posterity through oral and experiential means.1

What is co-reclamation?

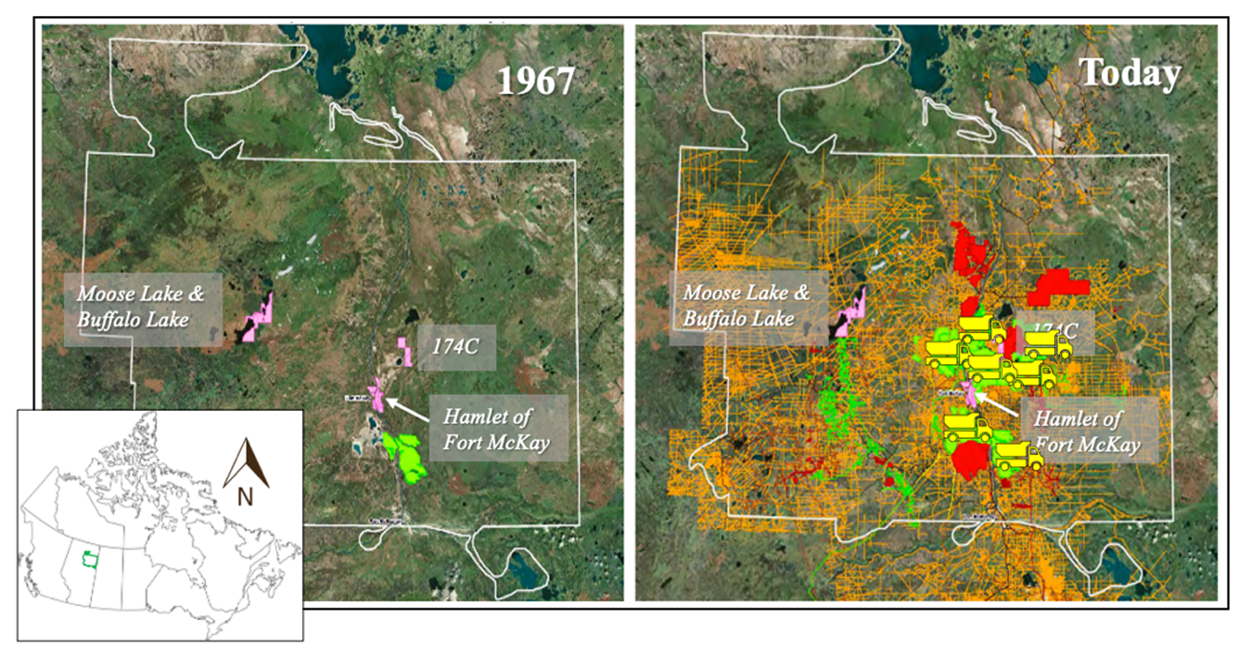

Beginning in March 2018, a collaborative approach to mine closure and reclamation, termed “co-reclamation”, was conceived and evaluated by academic and Fort McKay First Nation (Fort McKay) co-researchers, composed by community member and supporting staff. Since late 1960’s Fort McKay has been hosting oil sands projects on their traditional territory in Treaty 8, Alberta, Canada (Figure 1 and 2). This blog is based on the graduate research2,3 with Fort McKay co-researchers as part of the Co-Reclamation Project. The aim was to explore co-reclamation or a participatory and inclusive approach to mine closure and reclamation of lands disturbed by oil sands activities in the Fort McKay Traditional Territory to support the renewal of cultural landscapes capable of supporting Fort McKay’s traditional uses.

Figure 1

The project applied a “Two-Roads Approach”, which is an ethnoecological framework where both Indigenous and Western knowledge remain distinct or on their own road and there are opportunities for collaboration, or bridges, that bring together both roads to advance reclamation outcomes.

Photo Credit: Fort McKay First Nation

Figure 2

(Left) A birds-eye view of the oil sands industrial footprint within the Fort McKay Traditional Territory (white line) in 1967, the year oil sands activities started, and (right) present day.

Pink are Fort McKay First Nation reserve lands, green are active oil sands projects, red are proposed or approved but not yet operating projects and orange is primarily oil and gas exploration footprint. Truck symbols are oil sands mines where traditional land use planning in mine closure and reclamation was evaluated.

Map Credit: Fort McKay First Nation

The relationship between Fort McKay First Nation and reclaiming homelands

The people of Fort McKay have been living off the land for many generations. The sustainability of their culture is rooted in their traditional lands and waters which supply food and other resources for subsistence activities and a connection to their community, history, traditions, knowledge, and spirituality. For ~ 60 years, the oil sands industry has operated within the Fort McKay Traditional Territory and accumulated more than 162, 331 ha of mine footprint (Figure 2). Reclamation is the primary mitigation to land disturbance and related impacts to TLUs4.

Key project takeaways

While truth telling can reveal uncomfortable knowledge, it can also be the starting point for mitigating social inequalities, such as Treaty, Aboriginal, and Indigenous rights and the long-term impacts of ineffective mine closure and reclamation planning for the sustainability of homelands and Indigenous cultures. Below are truths and complementary reconciliation actions that emerged from the project.

Truths

- Mine closure plans lacked acknowledgement - of Fort McKay’s altered traditional territories, family memories, and impacted traditions2.

- Fort McKay is not represented in plans – While mines are targeting the return of traditional use, mine closure plans lacked evidence that local Indigenous communities’ questions, concerns, and knowledges led to Indigenous-informed closure decisions or accommodations2.

- Paternalistic and exclusionary decision-making - The Alberta government and mine companies make the decisions about mine closure and reclamation goals, target land uses, and reclamation design and timelines, while excluding Fort McKay’s unique worldviews, rights, and relevant local Indigenous Knowledge2,3.

- Systemic drivers of oppression – Mine closure and reclamation decision-making is driven by regulatory policy, directives, approval requirements, and western science-focused guidance documents and methods that do not include complementary and inclusive Indigenous ways of knowing, learning, and working as a good practice2.

Reconciliation actions

- Acknowledge the original peoples and lands – Reclaiming homelands starts with acknowledging the original peoples and what they’ve lost and exercising openness and creativity so that reclaimed cultural landscapes are “as similar as possible”5.

- Inclusive monitoring through Indigenous guardian programs – Include Fort McKay in all phases of reclamation planning, including monitoring. Indigenous Guardian Programs offer a modern model of an Indigenous stewardship ethic that has existed since time immemorial and is a component of the modern expression of inherent rights and cultural revitalization2.

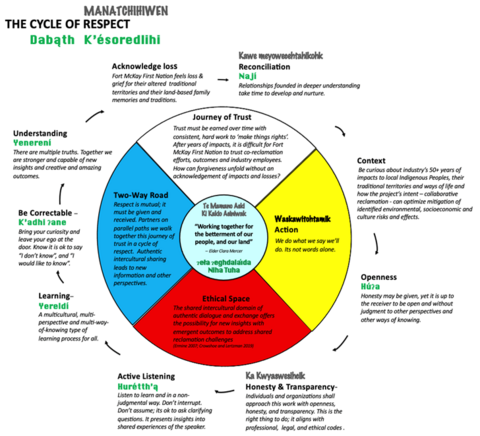

- Te Mamano Aski Ki Kakio Asiniwak (Cree) / ɂeła ɂeghdalaı́da Niha Tuha (Dene) / Working together for the betterment of our people and land – Realization of this Fort McKay-industry aspirational story can be supported by application of the Cycle of Respect, which guides oil sands operators and Government agencies in conducting ethical intercultural dialogue and meaningful engagement on mine closure and reclamation (Figure 3).

- Align human rights policies with project operations approval regulations and directives - The Government of Alberta must translate international6, national7,8, and provincial9 human rights policies into project operating approval regulations and directives since oil sands companies use them to develop their mine closure and reclamation plans.

Figure 3

The Cycle of Respect is an indigenized code of conduct with a set of principles to guide ethical intercultural dialogue and meaningful engagement on mine closure and reclamation.

Development of this intercultural tool was led by Elder Clara Mercer and land user Jean L’Hommecourt2.

References

1 Oil Sands Mining End Land-Use Committee. 1998. Oil Sands End Land Use Committee: Report and recommendations.

2 Daly CA. 2023. Exploring co-reclamation: gesturing towards intercultural collaboration and the renewal of Indigenous cultural landscapes after oil sands extraction in the Fort McKay First Nation Traditional Territory, Treaty 8, Alberta, Canada (doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

3 Davies Post A. (Forthcoming). Indigenous Guardian Programs as a model for evaluating traditional land use in post-reclaimed sites. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

4 GOA. 2022. Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act: Conservation and Reclamation Regulation. Edmonton (AB): Alberta Regulation 115/1993, as amended.

5 Daly C, L’Hommecourt J, Arrobo B, Davies-Post A, McCarthy D, Donald G, Gerlach SC, Lertzman DA. 2022. Gesturing toward co-visioning: a new approach for intercultural mine reclamation and closure planning. Int J Architecton Spat Environ Des. 16(1):11-32. https://doi.org/Doi:10.18848/2325-1662/CGP/v16i01/11-32

6 United Nations General Assembly. 2007.United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples.Resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly

7 Government of Canada. 2021. Government of Canada advances implementation of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

8 TRCC. 2015. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

9 Government of Alberta. 2013. The Government of Alberta’s policy on consultation with First Nations on land and natural resource management.