A presentation at the 2024 Eye Data and AI Summit

By Professor Anindya Sen

Cybersecurity & Privacy Institute

Professor in the Department of Economics, University of Waterloo

An Economic Test to Determine the Benefits and Privacy Costs of Sharing Health Data: Lessons for Public Policy

Helen Chen1 *, PhD; Maura R. Grossman2, J.D., PhD; Anindya Sen3, Ph

D; Shu-Feng Tsao1, PhD

1School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo

2Cheriton School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo

3Department of Economics, University of Waterloo

Key topics

- Research being done by Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute (CPI) faculty members

- An example of interdisciplinary work: using economics to determine data sharing

- When can sharing data benefit society?

- Some reflection

The CPI at the University of Waterloo – Path Breaking Research

- Professor Florian Kerschbaum is an expert on AI and cybersecurity and broadly speaking, his research looks at security and privacy in the entire data science lifecycle. Recent work focuses on the use of generative AI models on cybersecurity attacks.

- Professor Mei Nagappan’s research interests are in 'Big Data' Empirical Software Engineering. His work focuses on the protection of sensitive data, preventing security breaches, and ensuring the reliability and trustworthiness of software products, through secure coding with artificial intelligence (AI).

- Professor Diogo Barradas’ research is centred on protecting the metadata of communications established over the Internet through the development of privacy-enhancing technologies.

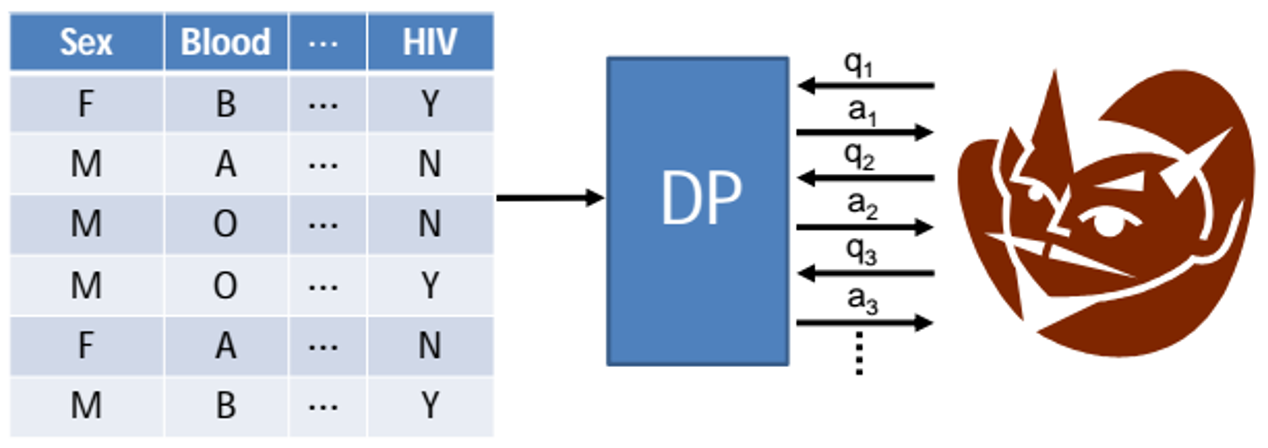

The CPI at the University of Waterloo – Differential Privacy

- Professors Xi He, Gautam Kamath – the field of differential privacy. Differential privacy is a rigorous mathematical definition of privacy. In the simplest setting, consider an algorithm that analyzes a dataset and computes statistics about it (such as the data's mean, variance, median, mode, etc.). (https://privacytools.seas.harvard.edu/differential-privacy)

- Such an algorithm is said to be differentially private if by looking at the output, one cannot tell whether any individual's data was included in the original dataset or not.

- In other words, the guarantee of a differentially private algorithm is that its behavior hardly changes when a single individual joins or leaves the dataset.

The CPI at the University of Waterloo – Synthetic Data

- Synthetic data is information that's been generated on a computer to augment or replace real data to improve AI models, protect sensitive data, and mitigate bias. (https://research.ibm.com/blog/what-is-synthetic-data).

- Helen Chen is one of our leading researchers.

- Synthetic data implies a cheap source of huge amounts of data at zero marginal cost.

- To keep information safe, companies follow strict internal procedures for handling the data. As a result, it can take a long time for employees to gain access to the anonymized data. Errors can also get introduced through anonymization that severely compromise the quality of the final product or prediction.

- Synthetic datasets can’t be traced to individuals but preserves the statistical properties of the original data, which is very important for individual privacy

But we are Interdisciplinary…..

- Research on strong cybersecurity stems from a desire to preserve and protect individual privacy.

- Adam Molnar is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and is exploring employee monitoring apps, which have become increasingly affordable and accessible, and provide a powerful degree of surveillance about workers: keystroke logging, location monitoring, browser monitoring, and even webcam usage.

- Leah Zhang Kennedy is an Assistant Professor in interaction design and user experience (UX) research at the Stratford School of Interaction Design and Business. Her research reflects interdisciplinary work between three focal areas: 1) building multimedia interactive tools to improve mental models for digital privacy and security; 2) understanding end-user and practitioner privacy perceptions and practices; and 3) defining the privacy and security user experience.

Policy Challenges

- Policymakers face the challenge of enabling data access while protecting individual privacy. The handling of health data has been subjected to stringent regulations by various laws, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States (US), the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in Canada, and the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) in the European Union (EU) (Shapiro, 2022).

- In their quest to test theories, models, algorithms, or prototypes, researchers and developers frequently rely on de-identified or anonymous, aggregated health data.

- However, it takes substantial time and resources to retrieve, aggregate, and de-identify data before it becomes accessible (Kokosi et al., 2022; Kokosi & Harron, 2022).

- One potential solution to this challenge is the creation of realistic, high-quality synthetic health datasets that mimic the complexities of the original data but do not contain any real patient information (Kokosi et al., 2022).

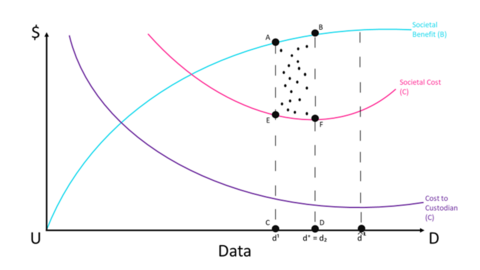

The Cost Benefit Approach

- An important contribution is the establishment of a cost-benefit framework that can be used to determine the net social benefits of the sharing of synthetic health data, or for that matter, any data. This is the focus of our discussion.

- Our approach is motivated by merger analysis in antitrust approach, which balances economic costs that might occur to consumers who might pay higher prices are a result of a lessening of market competition, which are then weighed against gains to merging parties in the form of cost savings. The methodology is known as ‘Total Surplus’.

- The Treasury Board of Canada (2022) also recommends a similar approach in weighing quantifiable benefits to different stakeholders against corresponding costs, to determine the desirability of competing public sector projects. If the marginal or incremental benefits of such projects exceeds incremental costs, then the project should be undertaken.

The Model

- Assume the existence of data (d), which is of interest to academic researchers who are interested in creating knowledge that will result in some benefit (B) to society.

- Further, there is a data custodian who has authority with respect to granting researchers third parties access to data. The data custodian experiences costs (C) in establishing infrastructure that stores data and enables access by researchers.

- The data custodian must use a societal framework model to evaluate whether allowing data access leads to net gains for society. Releasing the data allows third parties to conduct research and extract insights which leads to a societal benefit.

- To simplify our model, we will assume that the data may only be used by academics for publishable research. The mandate of the data custodian is to ensure that societal benefits from knowledge creation are maximized while minimizing the probability of individual privacy being compromised.

-

This is because the trade-off to knowledge creation from allowing access to data, is the probability that individual specific information contained in the database may be revealed, despite the use of privacy preserving technology by the data custodian.

-

If an individual’s privacy is compromised, then we assume that they will experience some harm (H), which can be monetary or non-monetary. The variable H captures both the probability of being harmed as well as the actual monetary and non-monetary amount of harm.

-

We assume that sharing more data leads to a higher probability of data being accessed by unauthorized third parties, and therefore, an increase in harm (H) to individuals.

-

In terms of other costs, the data custodian experiences economies of scale in maintaining data infrastructure and the employment of data protection technologies.

-

Specifically, while there are significant upfront costs in creating the infrastructure, average and marginal costs are equal and decline with each unit of data held by the custodian.

-

Hence, societal costs (SC) are the sum of the operations costs of the data custodian and possible harm to individuals.

An Example

- Suppose the data custodian is responsible for individual patient records at a hospital. The custodian decides to release data in response to a request from an accredited researcher interested in developing new insights on patient treatment

- Releasing the data always carries the risk of individual identification. Recent research has demonstrated that re-identifying individuals is possible even when released data are a partial sample of the entire dataset and with a limited number of variables.

- We shall assume that the individual experiences a loss of $20,000. This could occur if successful re-identification leads to information that enables a third party to launch a successful phishing or ransomware attack.

- What must also be considered is the probability of a successful attack, which is different from the probability of re-identification. For example, even if an individual’s information becomes available to a third party, the third party may not be able to execute a successful attack, if the individual is sufficiently educated on not to respond to phishing attacks or has suitable antivirus/anti-malware software installed on their computers.

-

For simplicity, we assume that individual harm (H) from a cyberattack facilitated by the release of patient-level information for research purposes, is captured by the below function;

H = H(pi, pa, M) = pi *pa * M

Where pi = probability of being re-identified from released data, pa = probability of a successful cybersecurity attack, and M = monetary damage from the cybersecurity attack. Essentially, this functional form captures expected harm from data release.

-

Assume that a group of university researchers have submitted a research proposal to access confidential individual patient-level data and the data custodian must evaluate the net benefits to society. The objective of the proposed study is to improve decision-making processes that have the potential to improve survival rates for cervical cancer patients.

-

Suppose that improved post-operative treatment recommended by machine learning algorithms from outcomes facilitated by access confidential data results, on average, in an increase in survival by 10 years for all cervical cancer patients treated in a hospital.

-

If the hospital treats 20 patients on annual basis and a conservative life-year value of $150,000. A back of the envelope calculation implies that aggregate societal benefits generated for patients treated at the hospital are $ 30 million.

-

However, assume that the sharing these data has compromised the privacy of 1,000 individuals in the dataset. Further, 80% of individuals have been subjected to successful cyberattacks and the average corresponding financial loss is $30,000.

Hence, pi = 1, pa = 0.8, M= $30,000. Therefore, harm to each individual = H = H(pi, pa, M) = pi *pa * M = 1 * 0.8 * 30,000 = $24,000.

Consequently, aggregate societal harm = 1,000 * $24,000 = $24 million.

-

If a dollar is valued equally by all stakeholders in this analysis, then sharing the data has made society better off, even though the number of people impacted by the data breach far exceed the number of patients experienced improved survival longevity.

Societal Net Benefit = Societal Marginal Benefit – Societal Social Cost = $30 m. - $24 m. = $6 million.

Conclusion & Limitations

- This paper also presents a cost-benefit framework that could be used to determine efficient levels of data sharing, aimed at balancing societal innovation against possible harm to individuals from compromises in their privacy.

- This framework is adapted from widely used cost benefit analysis principles in policy design and implementation.

- However, much work remains. This specific example has been adapted to health innovation, where reductions in morbidity and mortality have high values. What are the ramifications where innovation benefits cannot be so easily quantified?

- What are the individual costs to being identified?