“My grandfather had a little yellow piece of paper with a list of names and birthdates. The names were written in an unintelligible gothic script, but my grandfather was familiar enough with it to interpret them.... I recognized that there was a great deal of information hidden in that little list.”

Somewhere, teenager Lorraine Roth had heard about family trees, so she drew one up and took it to a family reunion. Later she learned that her grandfather had been wrong about one of the names—his grandmother was actually Irish! This was a surprise to Lorraine’s Amish Mennonite family.

It is easy to understand the lure of the family tree; trees are symbols of growth and knowledge. Yet trees are a relatively new way of describing family relationships. Well-heeled Roman families placed illustrious ancestors at the top of illustrations, from which their descendants flowed downwards connected by vines or garlands. By the 16th-century, however, noble families and even the emerging middle class were placing ancestors at the bottoms of charts, from which their descendants flowed upwards in tree form representing growth and progress.

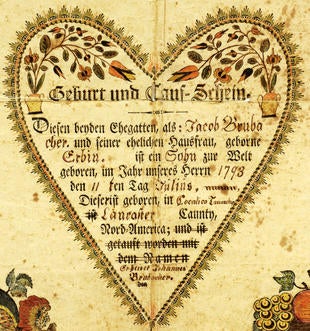

John Brubacher’s fraktur birth certificate. Brubacher probably purchased this form himself about the time he moved from Pennsylvania to Canada, about 1815. Since Mennonites did not practice infant baptism, he replaced the preprinted phrase “was baptized with the name” with “he was called Johannes Brubacher.”

In our current exhibit, Growing Family: Design & Desire in Mennonite Genealogy, the Mennonite Archives of Ontario celebrates the various ways Mennonites have chosen to visually represent family. Designing a family tree may seem like a simple act, but each tree requires the compiler, scribe, or artist to make choices: Who is in and out? What do we do when genealogy fails to represent our particular understanding of family? How do we account for loss? Behind each design are deeper desires for legitimacy, identity, and connection: Who are we? Where have we come from? Where are we going? How are we related, to the living and the dead? How will we remember, and be remembered?

Community Quilt

Grebel staff, faculty, students, and visitors created this beautiful and bright “3 Dudes” pattern quilt over the fall and winter terms.