Two years ago, Canadian Mennonite magazine published an article entitled “The church has left the building.” Referencing the closure of churches at the start of the pandemic, readers were prompted to consider what it means to be the church together when they are unable to gather. Although it felt unprecedented at the time, this expression of the church as a way of being is not new. The Mennonite church lives beyond the building, extending into the local and global community and expressing faith through relationships. In the summer of 2021, Mennonite Church Eastern Canada (MCEC) partnered with the Kindred Credit Union Centre for Peace Advancement to contract Grebel student and now Interim Coordinator of the Centre, Victoria Lumax (pictured right), to map these relationships to inform MCEC’s strategic planning process.

Over the years, MCEC’s relationships in local and global communities have flourished into an ecosystem of interrelated activities and priorities. While this offers innumerable opportunities, managing the complexities of this system can be a challenge. Systems mapping is a process through which these complex relationships are researched, analyzed, and presented to facilitate improved understanding and increase capacity for action. At the Centre for Peace Advancement, systems mapping is a skill that can be found across all of our programs, including the “Map the System” research competition which encourages students to develop their systems thinking skills.

Over the years, MCEC’s relationships in local and global communities have flourished into an ecosystem of interrelated activities and priorities. While this offers innumerable opportunities, managing the complexities of this system can be a challenge. Systems mapping is a process through which these complex relationships are researched, analyzed, and presented to facilitate improved understanding and increase capacity for action. At the Centre for Peace Advancement, systems mapping is a skill that can be found across all of our programs, including the “Map the System” research competition which encourages students to develop their systems thinking skills.

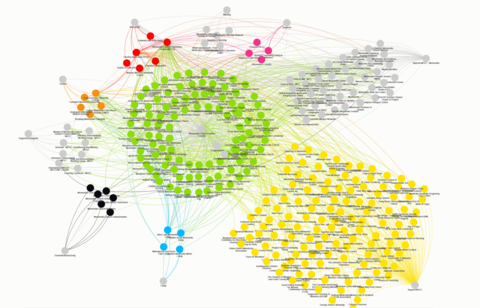

With support and direction from MCEC Executive Minister Leah Reesor-Keller and Centre Director Paul Heidebrecht, Victoria created a stakeholder map to visually present MCEC’s relationships with stakeholders, including member congregations, ministries, and agencies connected to the regional church, and how those relationships overlap and connect to one another.

This work garnered insight into the connectedness of MCEC congregations, the variety of partner agencies and ministries in relationship with MCEC, and the breadth of non-Mennonite connections within the ecosystem. One goal of this project was to determine the areas of mission overlap within the ecosystem. Through the system mapping process, MCEC confirmed that many partners share in their mission despite articulating it in different language. The process helped generate overarching ecosystem themes that could then be used to drive conversations around partnership and collaboration.

In reflecting on the process, Victoria is convinced that “systems mapping is critical to the Canadian church, especially MCEC, as it looks toward maximizing influence and impact in a complex world.” She notes that the value of the systems map is clear: “It lays bare hidden webs of interconnection and reveals incredible opportunities for growth. When an organization can understand their surrounding ecosystem from a bird’s eye view, it can move forward with a heightened sense of awareness and a renewed energy to fulfill its mission.”

In reflecting on the process, Victoria is convinced that “systems mapping is critical to the Canadian church, especially MCEC, as it looks toward maximizing influence and impact in a complex world.” She notes that the value of the systems map is clear: “It lays bare hidden webs of interconnection and reveals incredible opportunities for growth. When an organization can understand their surrounding ecosystem from a bird’s eye view, it can move forward with a heightened sense of awareness and a renewed energy to fulfill its mission.”

Beyond offering these invaluable insights, this system mapping project confirmed that the church has indeed left the building, and it did so long before the pandemic. Nevertheless, through relationships rooted in shared values, the church lives all around us, and one need only to map the system to find it.