Online technologies have changed the way we communicate, receive information and interact with officials during an emergency, such as a flood or wildfire.

We are notified by mobile applications when inclement weather is set to strike, we can find tsunami and flood warnings on Twitter, and Facebook notifies us if our friends or loved ones are "safe" when any disaster unfolds in their vicinity.

Canadian researcher Sara Harrison is interested in identifying opportunities for online collaboration and engagement between governments and citizens. Sara wants to understand how governments interact with their residents before, during and after a disaster. How are different governments across Canada doing this? Is there untapped potential in the way governments interact, educate and obtain information from their citizens? How could governments benefit from online citizen engagement?

To answer these questions, Sara has interviewed dozens of emergency management officials in North America.

Through her research, Sara has found several patterns:

- Governments tend to use online technologies to inform their citizens of imminent threats (e.g., sending tweets to warn residents about a developing flood threat), but do not leverage information created by citizens online for reducing the impacts of future disasters.

- Canadian governments are leveraging online citizen engagement in limited ways in comparison to American governments.

- There are benefits associated with using online technologies by Canadian governments outside of emergency response (e.g., warnings). But, organizational and demographic factors have been identified as factors that discourage the adoption of these technologies by governments.

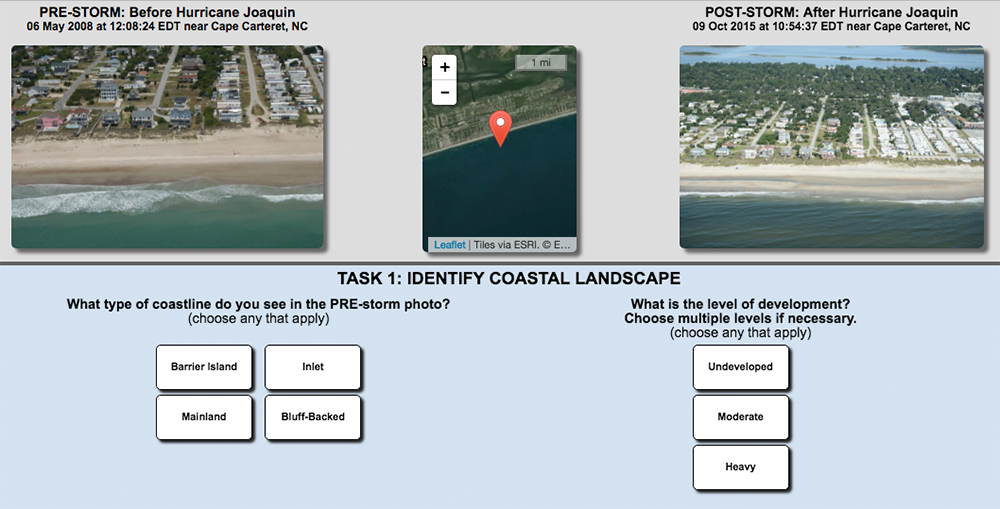

Sara highlighted iCoast as an example of an online tool specifically created by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for supporting efforts before a disaster occurs. The USGS states that iCoast was created with the intent that citizens would use their application and compare aerial photographs taken before and after the hurricane to spot the differences. The USGS sought citizen participation because computer models could not identify how the coastline had changed after the hurricane based on photographs.

Spot the differences before and after Hurricane Joaquin via iCoast

Sara says that this application was beneficial for the USGS because the data contributed by citizens helped inform models that can predict damages caused by hurricanes before they occur and support disaster mitigation efforts. These "citizen analysts" in turn reduce the need for government manpower to do the same comparative analysis.

As an additional benefit, coastal residents reported that through iCoast they were able to learn about hurricane hazards and of the risks they face as coastal residents. As a result, iCoast is a win-win for citizens contributing data and for governments using the citizen-contributed data.

Through her research, Sara found that Canadian governments are often hesitant to develop and use similar applications like iCoast (i.e., an application where users of online technologies contribute data for government use).

During interviews with Sara, some Canadian agencies expressed difficulties with verifying data submitted by the public for accuracy and credibility, and were concerned about their liabilities (e.g. making decisions based on information they receive from unverified sources). Canadian agencies would also require allocating resources including funds and specialized staff to this project, which is not always feasible. Finally, government policies are often non-existent, out of date, or restricting for this kind of citizen engagement technology.

For these reasons, most Canadian agencies continue to rely on call centers, 211 and 311 numbers and email for communication.

Sara suggests the following solutions to overcoming barriers and constraints for the use of online and mobile technologies for disaster risk management in Canada:

- Allow enthusiastic employees to have a chance to make decisions and lead a new approach.

- Build partnerships with neighboring jurisdictions, tech-savvy private sector organizations, or with non-profits working in the field. This will expand resources and know-how.

- Build a set of validation tools. This includes collecting user information, geotagging pictures and videos to identify trends, or use social media management software. Build a list of trusted sources, and issue ‘reporting guidelines’ for the public.

- Engage with citizens online well-before an event to build a strong relationship of trust between government and citizens so that in times of disaster, two-way communication is already integrated into regular operations.

Sara Harrison is continuing her research in this subject matter as a PhD Candidate in New Zealand at Massey University’s Joint Centre for Disaster Research. Read more about her work and for one of her recent peer-reviewed publications.

Sara Harrison conducting research in Angus, Ontario in the aftermath of the 2014 tornado