Background

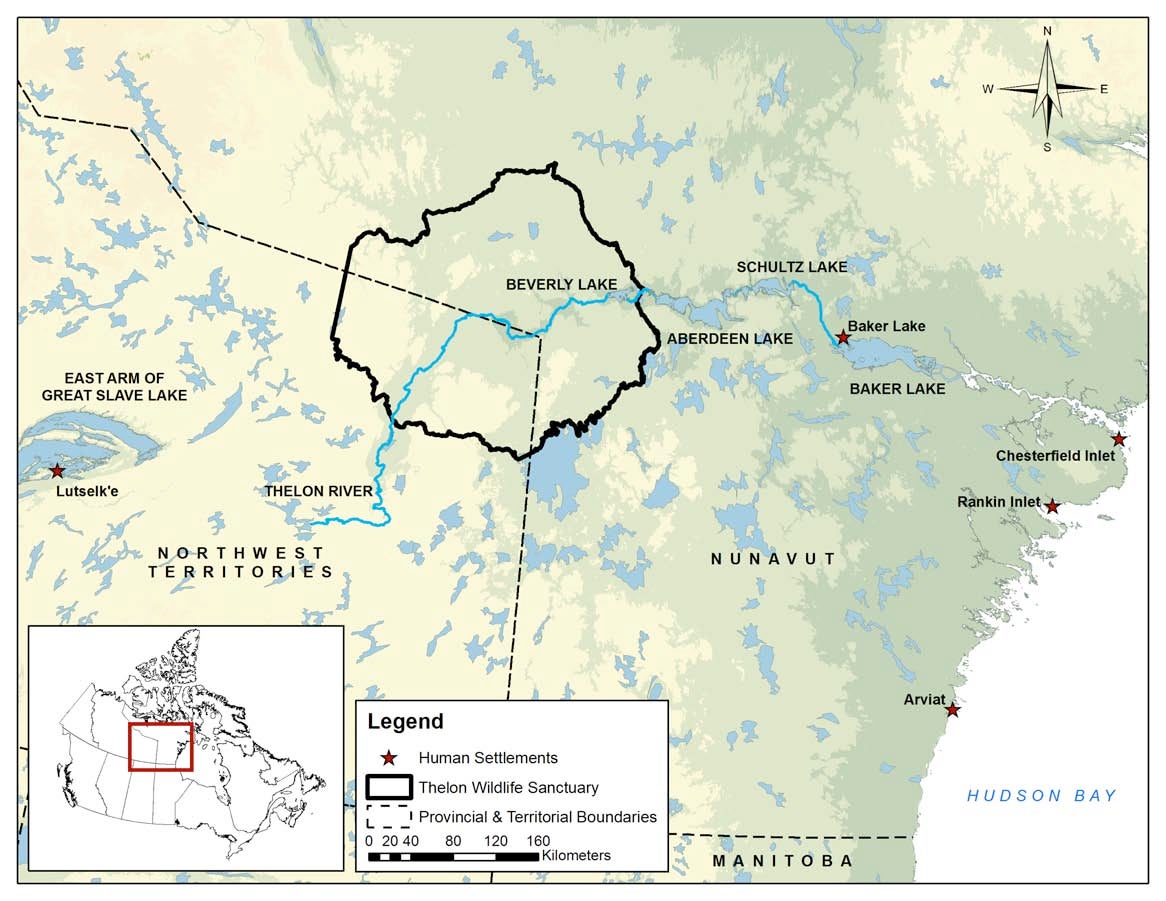

With headwaters in Canada’s Northwest Territories, just east of the height land that separates the Hudson Bay and Mackenzie River watersheds, the Thelon River flows out of the boreal forest and east across the tundra and into Nunavut (Figure 1). The river stretches approximately 900 kilometres across habitat that is ideal for migratory herds of caribou and other large mammals like muskoxen, grizzly bear, wolf, and moose.

Figure 1. The Thelon River (Source: Will Van Hemessen)

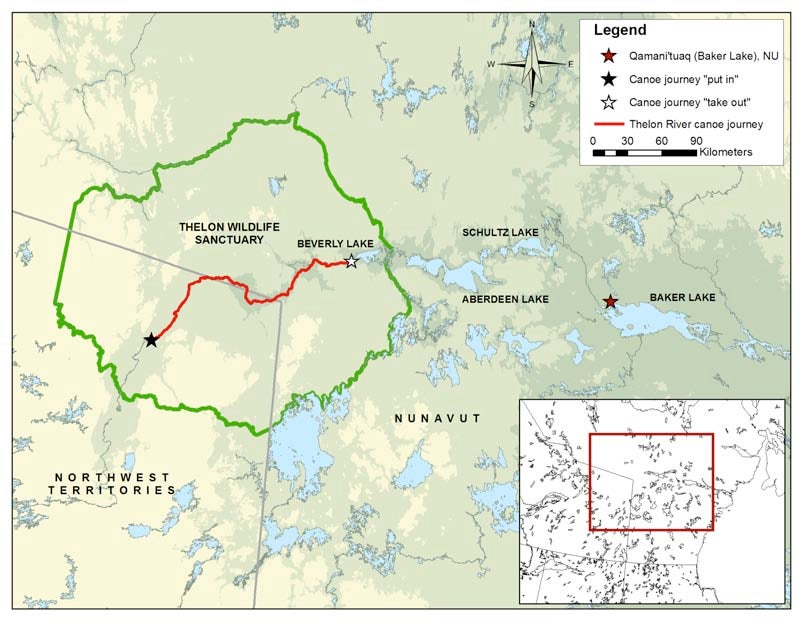

This territory is the homeland of various Aboriginal societies. Archaeological records show that, for close to 8000 years, human occupation of the area has been linked to caribou as the main source food, clothing, shelter, and tools. Current inhabitants include descendants of the Caribou Inuit, who moved inland from the Hudson Bay coast after the Chipewyan Dene left the area in the late eighteenth century. While Dene and Inuit traditions and use of the Thelon are different, the river has remained an important place for both peoples for many generations. At caribou water crossings, for example, hunters and families would drive or wait for caribou to cluster and become vulnerable while swimming. Stone tent rings, chipping sites, inuksuit, caches, and kayak stands are currently located at these places. Both the Dene First Nations in Lutsel K’e, NWT, located on the east arm of Grea Slave Lake, and the Inuit of Baker Lake, Nunavut, located at the eastern terminus of the Thelon, have indicated that their knowledge, subsistence practices, and cultural memory are firmly connected to the Thelon River. In addition, there is an increasing awareness of the Thelon’s historical and contemporary significance to Métis Peoples. Among nature-based tourists, including recreational canoe travellers, the remoteness and naturalness of the Thelon River mark it as an ideal wilderness destination. The first modern recreational canoe trip down the Thelon River occurred in 1962. Since then, hundreds of independent and commercially guided canoeists have travelled portions of the river on multiple-day expeditions. Many of these canoeists are motivated to visit beautiful landscapes, encounter wildlife, and experience first hand similar journeys as the early Euro-North American explorers. Recreational canoeing along the Thelon has also been encouraged by various conservation initiatives. For example, the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary, which was established in 1927 by the Canadian government to protect muskoxen and caribou, represents one of the nation’s largest and earliest established protected areas. Canoeists want to experience at least a small portion of this 56,000 km2 nature preserve. More recently, a section of the Thelon was designated under the Canadian Heritage River System to celebrate the watershed’s natural, cultural, and recreational values. One intention of this initiative was to persuade more nature-based tourists to visit the Thelon region.

Study purpose

Baker Lake Elders shared knowledge during this project (photo by B. Grimwood)

The Thelon River is a special place that means different things to different people and is used and experienced in multiple ways. The purpose of the study was to work with river tourists (wilderness canoeists) and river inhabitants (residents of Qamani’tuaq/Baker Lake, Nunavut) to document knowledge about the Thelon, and to share this knowledge within and between participant groups. By documenting and sharing different knowledge, it was expected that the research would a) celebrate the different uses and meanings of the Thelon River; b) raise cross-cultural awareness and understanding; and c) cultivate a sense of shared responsibility to and for the Thelon River among its visitors and inhabitants. These outcomes are important in order for people to work together and respond to the many social and ecological changes occurring in northern regions.

Research approach

The study employed community-based and participatory research approaches. This style of research entails working with communities (in this case Inuit and canoeists) and involving them as much as possible in all aspects of the project. For Picturing the Thelon, participants helped to clarify project objectives, determine and collect data, and analyze and interpret data. A number of community members supported the project by working as research assistants, community liaisons, or interpreters.

Research methods

Three methods were used in the research: photographic interviews, experiential river trips, and community workshops. A summary of these methods is presented in Table 1. It is important to note that these are all qualitative research methods, which focus on trying to understand human behaviour and experiences in depth, rather than identifying facts.

| Module | Group/Type | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Photographic Interviews | People of Baker Lake | Ten participants, 147 photographs |

| Canoe tourists | Twenty eight individual participants, one family, 345 photographs | |

| River Trips | Snow Machine |

a) Baker Lake to Halfway Hills, 1 day, 73 kms b) Baker Lake to Kangirjuaq, 1/2 day, 20 kms |

| All-terrain-vehicle |

a) Baker Lake to Prince River, 1/2 day, 33 kms b) Baker Lake to Kangirjuaq, 1/2 day, 24kms |

|

| Foot | Baker Lake to Blueberry Hill, 1/2 day, 7kms | |

| Motorboat | Baker Lake to Kazan River, 1 day, 182 kms | |

| Canoe | Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary, 10 days, 240 kms | |

| Workshops | Baker Lake Arctic College |

a) Nine participants, 1.5 hours workshop b) Seven participants, 1.5 hour workshop |

| Baker Lake Elders | Ten participants, 2.5 hour workshop | |

| Baker Lake Residents | Two participants, 2 hour workshop | |

| Baker Lake Residents | Two participants, 2 hour workshop |

Photographic interviews

This aspect of the project involved 38 individual participants (ten Baker Lake residents and 28 canoe travelers). Each of these participants was asked to share up to 12 Thelon River images that they had taken and which represented to them their Thelon experiences and their idea of responsibility. A total of 492 photographs were contributed. Individual participants also discussed their photographs in a face-to-face conversational interview or an email questionnaire. Many stories filled with vast knowledge, meaning, and experience related to the Thelon River were communicated.

Experiential river trips

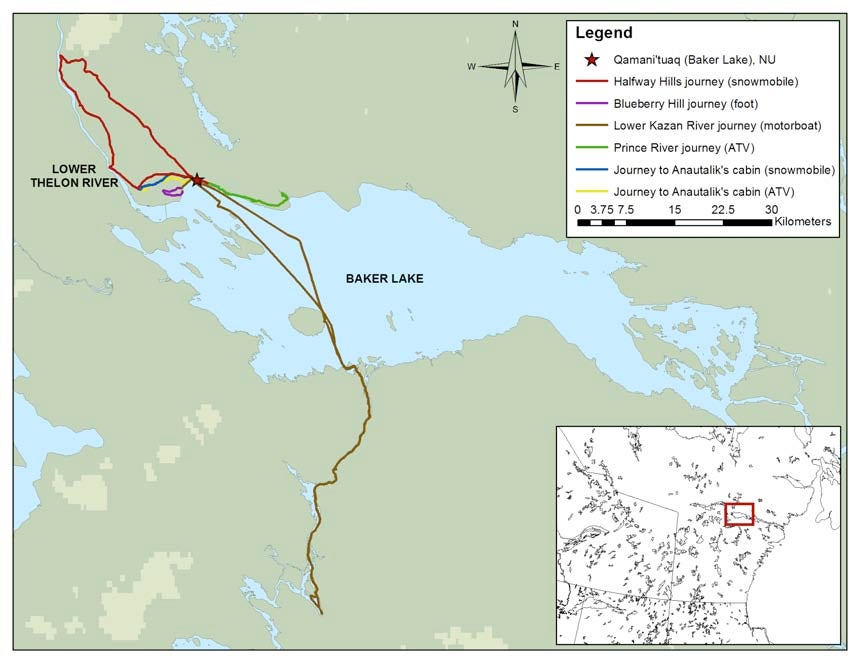

This component of the project involved Bryan’s participation in river journeys with Inuit and canoeists. A total of seven journeys using various types of transportation over a range of distances were documented using photography, field notes, and GPS tracking. Six of these trips started in Baker Lake and ranged from half a day to a full day in length. The routes of these journeys are displayed in Figure 2. One trip with canoeists was 11 days long. This journey was guided by Alex Hall of Canoe Arctic Inc. and involved travelling through the heart of the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary (Figure 3).

Community workshops

A series of community workshops were implemented so that information from the photographic interviews could be shared with broader Baker Lake and canoeing communities. At these workshops, participants examined photographs and used these to analyze and interpret the experiences and meanings associated with the Thelon River (i.e., their own and those of others). Unfortunately, due to time constraints, only one workshop occurred with a group of canoeists.

Outcomes

The purpose of this research was to work with canoeists and Inuit residents of Baker Lake, Nunavut to document knowledge about the Thelon River, and to share this knowledge within and between these groups. The research was intended to describe different perspectives, foster understanding, and cultivate responsibility in relation to the Thelon River. Because these objectives are broad, the research materials collected could have been interpreted, synthesized, and reported in many ways. In writing his PhD dissertation, Bryan focused attention on three thematic outcomes.

1. Engaged acclimatization: An approach to responsible research in Nunavut

Figure 2. River trips departing from Baker Lake (Source: Will Van Hemessen)

One of the challenges of the project was the fact that Bryan is not a resident of Baker Lake. When people are ‘outsiders’ to a community, they can often be unknowingly disrespectful. Bryan wanted to ensure that his interactions with participants and other residents of Baker Lake were positive, courteous, and fair. The approach that evolved as Bryan developed responsible research relationships with Inuit was called engaged acclimatization. The process involves direct experience in new settings and values exploration, reflection, care, creativity, and uncertainty as fundamental to research. Four aspects characterize engaged acclimatization.

- Building relationships: the intention of engaged acclimatization is for a researcher to continuously seek out and be open to new ideas, other cultures, and different places.

- Learning: the approach of engaged acclimatization contrasts research driven by expertise, certainty, and efficiency. Instead, a researcher adopts the perspective of a learner whereby humility, ambiguity, and the willingness to adapt to change characterize the research process.

- Immersion: to practice engaged acclimatization, a research must engage with place-specific experiences and ways of knowing. This requires that researchers immerse themselves in the communities with which they seek to learn and work.

- Activism: engaged acclimatization facilitates change by orienting researchers to the capacities within a community. When doing research is about relationships, learning, and immersion, the focus shifts from discovering true facts to working with others towards positive futures.

2. Nature-culture values: Commonality across different cultural practices

Figure 3. The Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary River Trip (Source: Will Van Hemessen)

Values are often separated into “natural” and “cultural” categories. For example, the Canadian Heritage River System distinguishes natural and cultural values in their designation of nationally celebrated rivers. A limitation of this approach is that one value type often gains preference over the other. We see this in tourism related materials that promote the Arctic as an exotic natural place that is pristine, vulnerable, and in need of protection. These nature-based values can overshadow the cultural practices of Inuit and other northerners who continue to rely on their environment for subsistence (e.g., hunting and fishing). This leads to potential conflicts between ecotourists and hunting peoples like Inuit, thus deterring cooperation between groups.

The documentation of experiential river journeys was used to compare the Thelon River travel practices of canoeists and inhabitants. The intention was to analyze these different cultural practices as expressions of underlying and potentially shared values. The result of this analysis was the identification of three valuebased metaphors that show how nature and culture are not distinct, but rather deeply interrelated. As research outcomes, these metaphors provide ways for thinking about the commonalities that exist between different uses and perceptions of the Thelon River.

- Emplacement: the value of being and becoming connected to the Thelon River as a special place. Emplacement is expressed in many ways, for example:

- When people anticipate Thelon River travel by organizing clothing and equipment, preparing food, reading literature, or practicing skills. The Inuktitut word for this “getting ready” activity is pagnatiit.

- By physically sensing the environment through touch, sight, sound, smell, and taste. These sensations also allow relationships to be made with the heritage of the Thelon. A canoeist, for example, tried making stone arrowheads. Smelling trees near Beverly Lake brought back fond memories for an Inuk Elder of her life as a young girl.

- Through the accumulation of place-based ecological knowledge and skills.

- By conveying meaning and ecological understanding through interpretation, stories, and place names.

- When people document travel activities using photography, journaling, story telling, and by collecting mementos.

- Wayfaring: the value of “knowing as you go”, or perceiving and engaging the Thelon River with multiple senses as an integral part of travel. Wayfaring is expressed in paddling, motor vehicle, and walking practices. For example:

- Using paddles as extensions of their arms, canoeists work their bodies in tandem to position their canoe relative to current or wind for a desired effect. When winds pick up or river obstacles are encountered, canoeists position themselves for more calculated and concentrated strokes.

- Oriented by river corridor or eskers, and unfettered by extended hours of Arctic summer daylight, canoeists walk, individually or in small groups, to explore campsite surroundings, follow animal tracks along the beach, or examine glacial deposits upon a hill.

- While safe motorboat routes up rapids are inscribed into local Inuit knowledge systems, everyday navigation demands an ability to read the river for deepwater channels, obstacles, and slower moving micro-currents, and to manoeuvre the motorboat in response to river features encountered. The driver of a motorboat tends to stand to scout the river, scan the shoreline for guidance in the form of inuksuits, or watch the happenings of other vessels. It is a subtle but well-rehearsed skill of manipulating the steering wheel and/ or applying the appropriate amount of throttle that enables effective and safe navigation.

- Gathering: the value of bringing together or building up social bonds. The Thelon River is a place that inspires people to have shared experiences and develop a sense of community. Gathering is expressed through invitations, creating camps, and sharing food. For example:

- An Inuk Elder’s invitations to join her at her cabin led to several episodes of inter-generational and inter-cultural knowledge sharing.

- Canoeists often seek out others to join them on evening walks along eskers or on the tundra.

- On the days with little wind, canoeists assembled a mesh tent so that they could enjoy meals in relative bug-free comfort. The bug tent had the effect of enclosing the group within a bounded space, the comfort of which was reflected in the ease that informal conversation transpired.

- While on the land, canoeists and Inuit congregate and converse around hot tea, fresh and/or dried caribou meat, bannock, and store-bought snacks.

3. Tracks and traces: Natures, responsibility, and identity

The 492 photographs contributed to the project by canoeists and Inuit were analyzed by coding and counting the different elements presented in the images (i.e., the photograph contents). “Tracks and traces” emerged as a thematic category in these photographs. These images depict various signs of human and/or wildlife presence within the Thelon River watershed. They include things like snowmobile tracks, trapper cabins, stone arrowheads, shed antlers, paw prints along an esker, and even the wake behind a canoe. The tracks and traces theme was made up of various components. “Structures that signal,” for example, consisted of human created markings that highlight a particular river feature, activity, or moment. Examples include inuksuit, cairns, graves, or tent rings of former Inuit encampments. These contrast images coded as “human settlement,” which include buildings fixed in location for long-term shelter (e.g., hunting cabins or houses). Photographs coded as “tracks” include foot prints or paths created on land or water by humans (and our machines), grizzly bear, wolf, caribou, or geese. “Remains” refers to antlers, eagle feathers, or skulls that linger upon the land. It is interesting to note that tracks and traces allow us to read something about events or activities that have occurred along the Thelon. They tell stories of landscape history or memory. The tracks and traces theme directed a second level of analysis whereby the physical contents of the photographs and other research materials were interpreted for underlying meaning or symbolism related to responsibility. This analysis revealed that both canoeists and inhabitants intentionally make certain traces present upon the landscape, while intentionally trying to make other traces absent. For example, the canoe guide involved in the study would reveal to canoeists wolf dens or ancient stone arrowheads that likely would have otherwise gone unobserved. Inuit Elders explained that signs from a caribou harvest would be removed from the landscape so that caribou migration patterns would not be altered. Each of these activities contributes to making the Thelon River appear a certain way.

The analysis also showed that certain activities of making traces present or making traces absent expressed responsibility to and for others. In other words, the activities of canoeists and inhabitants that shape what Thelon looks like are sometimes performed in a spirit of care, concern, and respect for other river travellers. An inuksuit, for example, is a trace left by an Inuk hunter to identify to other Inuit the direction from which caribou travel. Alternatively, canoeists may avoid leaving fire pits, or other visible scars, so that subsequent groups of canoeists can discover the Thelon River as a pristine waterway. Importantly, these expressions of responsibility are often related to how inhabitants and canoeists see themselves as stewards of the river. Responsibility to and for others can be an expression of personal and social-cultural identity.

Conclusions

First, the research drew attention to the multiple uses, perspectives, and relationships associated with the Thelon River. Second, the research contributed interdisciplinary insights and real-world descriptions that are novel to the study of tourism ethics, nature-based tourism, and Arctic tourism. It demonstrated, for example, ways in which touristic and inhabitant practices are indeed different, but also how they have much in common. Third, and most importantly, these understandings were achieved in partnership with tourist and Inuit research participants. This models a learning-centred, knowledge sharing, and inclusive approach to research that is highly relevant in light of contemporary contexts of Arctic change. Specifically, it is an approach that can help create safe spaces for cross-cultural and inter-regional dialogue, a prerequisite for cooperation, partnership, and responding effectively, and responsibly, to change.

Of course, Picturing the Thelon is not without limitations. To date, the project has not engaged with Dene and Métis communities that, like Inuit, have long histories of knowing the Thelon as a homeland. Nor has the project integrated the perspectives of relevant land, water, and conservation institutions and government departments. Ongoing and future research initiatives will attempt to involve partnerships with these diverse stakeholders.

Picturing the Thelon - Natures, Ethics, and Travel within an Arctic Riverscape - Acknowledgements