A full copy of this paper can be obtained from the author, Dr. Andrea Stapleton (andreas@mun.ca).

Summary

All companies have limited resources. Where they choose to invest those resources presents an opportunity cost because an investment in one project or product means not investing in another. Generally, leaders in companies choose to invest in projects that they believe will deliver greater returns than the projects they reject.

Due to any range of factors, projects and new products or services frequently fail to deliver expected returns. This leaves managers with a decision: should they continue to invest in an underperforming project, or should they divert that investment to a more promising venture? These decisions are important; they impact the firm’s profitability and competitiveness.

In many organizations, the decision to reinvest in or withdraw support from an underperforming project is left to the manager who made the original decision to invest. This leaves firms vulnerable to the psychological biases and personalities of those managers. Cognitive dissonance theory (CDT) suggests that when a manager learns that a project he or she initiated is failing, it creates a conflict (dissonance) with their perception of themselves as a competent manager. This triggers the manager’s desire to protect their ego, otherwise known as self-justification theory (SJT). Managers may also want to protect their reputation by not admitting to failure. These biases help explain why managers so often escalate poor investments, where diverting money to a more promising venture would be the wiser choice.

Again, the propensity that many managers have to “throw good money after bad” costs organizations a great deal. Extensive research has been conducted to investigate the causes and offer remedies. Some overcome the problem by assigning the decision to a separate manager, but for a variety of reasons, many firms leave it to the original decision-maker. It is important then to explore ways to help managers overcome their biases so that they can make better decisions.

In this study, the author investigates the use of perspective-taking as one means to overcome the influence of SJT and face-saving biases. Perspective-taking – in which a person “puts themselves in the shoes of another” – has been used successfully to mitigate self-centered and/or insensitive behaviors in many aspects of life and business.

The author also explores the effect of perspective-taking on managers with a narcissistic personality trait. According to a range of studies, the attributes of mild narcissism – an inflated opinion of oneself – is increasing in the population. Normally, high self-esteem among narcissists (even if unwarranted) shields them somewhat from threats to their ego or reputation (i.e., they think so highly of themselves that it takes more to threaten their ego and they are less sensitive to how others perceive them). This being the case, they should be less likely to escalate investments in underperforming projects and, therefore, more likely to make good decisions in this respect.

Assumption/Hypotheses

The author grounds her experiments in three assumptions. Her first assumption is that managers who participate in perspective-taking will be less likely to escalate spending on poor performing projects. Second, that narcissistic managers are less inclined than other managers to escalate their investments in underperforming projects, and third, that when managers participate in a perspective-taking exercise, the effects (to reduce bad decisions) will be more pronounced in non-narcissistic managers.

The Experiments

The researcher conducted an experiment with 228 managers as participants. On average, participants had 17 years of work experience and one-third had faced decisions in the past in which they had to choose whether or not to keep investing in an under-performing initiative or project. The participants were assessed using a series of tests to place them into narcissist or non-narcissist groups. Each was put into the role of a manager who was asked to choose to invest a sum of money into one of two similar projects. Each project was expected to generate returns of 23.5%, a rate of return significantly better than the firm’s general target of at least 15% internal return on investment (IRR).

Next, half of the participants were told that after three years, their investment was underperforming at 14%, the other half were told it was performing as expected at 23.5%. Half of the former group of participants then participated in a perspective-taking exercise. They took on the role of a manager called in to decide whether to reinvest (escalate) in the underperforming project or divert the funds to a project currently earning a 17% IRR.

All participants were asked to rate the likelihood that they would to continue investing in the underperforming project on a 10-point scale, 1 being “definitely terminate the project,” 10 being “definitely continue the project.”

Results

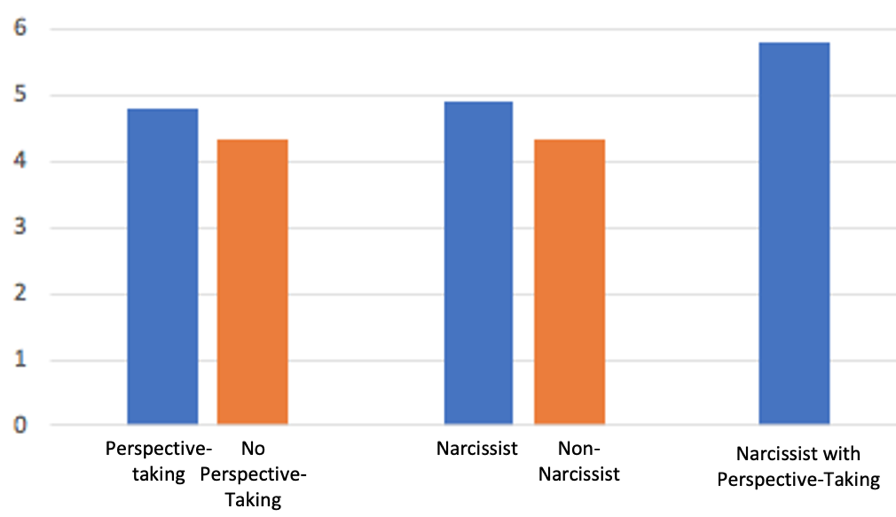

Surprisingly, the author found all three of her assumptions to be false. Narcissistic managers are, on average, slightly more likely than others to reinvest in an underperforming project. Moreover, narcissistic participants who participated in the perspective-taking exercise, grew more likely to reinvest. Even non-narcissistic managers who participated in perspective-taking were only slightly less likely to reinvest than non-narcissistic managers who did not participate in perspective-taking (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Likelihood to Reinvest (Escalate)

Key Takeaways

- First, realize that ego and reputation-protecting biases affect most managers, whether or not they are narcissistic. When it comes to making decisions about whether to continue investing in an underperforming project, invite managers who didn’t participate in the original decision to help determine whether to keep investing.

- Perspective-taking exercises have proven valuable in helping people acknowledge their biases and develop empathy, often leading to better clarity in decision-making and/or improved relationships. This research, however, demonstrates that personality and other factors sometimes cause perspective-taking to fail or even backfire. From the results of this research, it appears likely that perspective-taking actually heightens a narcissistic manager’s need to save face, making them more likely to make bad decisions. Bear this in mind when considering whether or not to use perspective-taking in similar circumstances.

- Keep encouraging employees and leaders to take other peoples’ perspectives but be aware that it is not a magic bullet. The circumstances and/or type of decision in question – and people’s personalities – should be taken into consideration.

Q & A

We asked the author the following question about their research.

-

Given the results of your study, what advice would you give managers about using perspective-taking in similar circumstances or in general?

The theory supporting the use of perspective-taking (PT) as an effective de-escalation strategy is sound. We know it works for groups deciding whether to continue funding a poorly performing investment.

I suspect that in my study the PT prompt backfired because it made managers see themselves from the perspective of an outsider and that triggered their sensitivity that they may be viewed negatively.

Theory suggests PT prompts are useful when individuals do not have to reflect upon themselves and their prior decisions. For instance, they are useful when auditors adopt the perspective of their client.

Humans are complex. Abandoning attempts to improve decision-making simply because the tool or technique does not work for everyone seems rash. Rather than abandon perspective-taking, I would suggest that it has a place in organizations and requires careful thought before being implemented. While it may not universally reduce managers’ escalation of commitment, there may be other decisions for which PT is effective.

That said, I would prefer to see more research examining PT and escalation of commitment before we recommend abandoning PT for this type of decision.

You mention that perhaps the IRR difference was not strong enough; e.g., maybe if the underperforming project were generating IRRs of only 7% rather than 14%, it would have made a difference. To what extent do you think this change to the experiment would have generated different results?

This is an empirical question that requires more experimentation to answer.

Using a metaphor, narcissists are attracted to shiny objects. Perhaps the percentages I used in my study were not ‘shiny’ enough. Perhaps narcissists need a more attractive alternative to overcome their concern about face-saving. It is also possible that making the alternative more attractive motivates everyone to choose it. If so, we would not be able to detect an effect of narcissism on escalation of commitment.

More questions? Please forward any additional questions you may have to the author, Dr. Andrea Stapleton at Memorial University, Newfoundland: andreas@mun.ca.