A full copy of this paper can be obtained from the author, Dr. Theo Stratopoulos at the Center for Performance Management Research and Education (CPMRE): tstratopoulos@uwaterloo.ca

Introduction

Firms considering new technologies face a dilemma: adopt a promising but untested technology early or wait until it’s a proven winner. Those who move early will either gain a competitive advantage or waste resources. Those who wait might avoid a loss but could miss out on significant gains.

Logically, all other factors held constant, an organization that deploys a valuable technology before its competitors stands to gain a competitive advantage. But how does a buyer know whether a new and as yet unproven technology will turn out to be valuable? And if so, how long might their advantage last?

Likewise, for companies that develop and sell new technologies, the path to success can seem mysterious and unpredictable. Having a better sense of when widespread adoption of their technology will occur would help them plan their sales, production, and support services, and guide them in knowing approximately when they should develop and launch new products as their current products “go mainstream.”

This research offers a simple and effective framework for estimating the duration of competitive advantage that earlier-than-average adopters can expect from a technology, and a method for estimating the time to widespread adoption of technology. As such, it benefits both technology producers and buyers.

Background

The research identifies three necessary conditions for estimating the duration of competitive advantage for early adopters of new technology. First, it must be clear when the technology was first made available (i.e. a start date). Second, the technology must be capable of driving lower costs and/or increased revenues in the adopting firm, and third, the technology must present a barrier to adoption (e.g., price, complexity, etc.). The longer it takes for a majority of the competition to adopt the technology, the longer the period of competitive advantage.

In this study, the framework is tested against two technologies that meet the criteria above, and have gone through the technology adoption cycle to become mainstream business applications: Cloud Computing and Enterprise Resource Management (ERP) solutions.

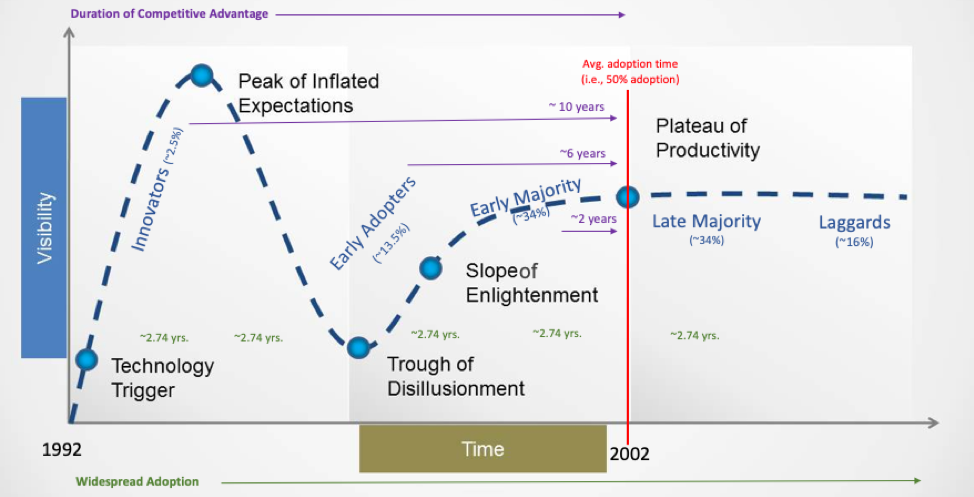

The adoption cycle progresses from the experimental stage, where only the most adventurous firms (aka “innovators”) adopt the technology (about 2.5% of eventual adopters). Next come “early adopters” (~13.5%) who learn from the innovators but still face considerable risk. Depending on the success of early adopters, sales of the technology tend to accelerate or evaporate. Technologies succeed (i.e., go mainstream) when a rush of “early majority” (~34%) adopters enter, followed by the “late majority” (~34%) and finally, “laggards” (~16%).

This adoption cycle roughly maps to Gartner’s Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies in the following way. Innovators join in the experimental, or “Technology Trigger” phase fueling the “Peak of Inflated Expectations” phase (See Figure 1). Early adopters join as the technology is coming out of the Trough of Disillusionment and into the Slope of Enlightenment phase. Early majority adopters get on the bandwagon next as the technology moves toward the Plateau of Productivity. At this point, the technology hits its average adoption point, meaning that 50% of adopters are now onboard. The late majority and laggards follow as the technology goes mainstream (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Example Gartner Hype Cycle With Adoption Cycle Overlay

It follows that the three types of first adopters (innovators, early adopters and early majority) benefit from periods of competitive advantage varying in length, i.e., from the launch of the technology to the point midway between the early majority and the late majority stage where the average adopter joins. Beyond this point – the point of average adoption – firms still benefit from implementing the technology, but no competitive advantage accrues because many if not most of their competitors already have it. The researchers argue that if the adoption cycle follows an approximately bell-shaped distribution, the time from the launch of the technology to the 50% adoption point is equal to three standard deviations (SD) (i.e., equal periods of time).

Methodology

The researchers use publicly-available data from Google Trends (web searches), Lexis-Nexis (magazine articles), WorldCat (book titles) and Gartner Hype Cycle reports to assess the rate of changing interest in a technology. The researchers reason that interest in the technology should map to its growing acceptance and perceived value as it progresses through the cycle from innovator to average adopter.

In this study, ERP and cloud computing – from launch/availability date through the entire adoption cycle – were used as test cases. For example, cloud computing emerged in 2006. Interest in it – as evidenced by a Google Trends search on “cloud computing” and a similar Lexis-Nexis search – began in 2007 and peaked in 2011. This data is consistent with Gartner’s estimation of the Technology Trigger to Peak of Inflated Expectations phases in its reports on cloud technologies between 2004 and 2015. This suggests a 5-year period of competitive advantage between the innovator (launch of product in 2006) and the early adopter stage for this particular technology (1 SD).

To estimate the time between the early adoption stage and that at which a technology is set to go mainstream, it is useful to look at the number of books released about the technology. Publishers time the release of books for maximum potential sales. Therefore, titles on new technologies tend to emerge as the masses begin to adopt it (i.e. the early majority).

The researchers performed a WordCat search on “cloud computing” and found that the number of new books on the topic peaked in 2013. This equates to a 7-year block of time between the innovator (2006) and early majority adopter stage (2013) for cloud computing, therefore two SDs (units of standard deviation) between the innovator, early adopter and early majority phases of 3.5 years each (7/2). This conflicts with the first estimate of a 5-year SD between the stages.

To test the accuracy of the second estimate, the researchers projected that by 2016 (~3.5 years) cloud computing should have reached the next stage in the adoption cycle – the beginnings of the late majority and the point of average adoption (50% of adopters using the technology). A review of the data provided several pieces of corroborative evidence suggesting that indeed, by 2016, cloud computing had reached or slightly exceeded the point of average adoption, including in small and mid-size firms. Thus 1 SD was estimated at 3.5 years.

A similar process was followed to estimate the duration of competitive advantage for early adopters of ERP technology. In this case, the technology arrived in 1992 and followed a typically slow innovator stage lasting several years. However, due to Y2K fears, the dot-com explosion and other factors, adoption rates accelerated sharply in 1996 such that the phase of mainstream adoption occurred by 1999 even though the point of average adoption wasn’t reached until about 2004. Given these accelerating factors, the researchers allowed for two stages (two units of SD) between 1992 and 1999. The SD (the time between the adoption stages) was calculated at about 3 years giving an innovator who successfully implemented ERP in 1992 roughly a 12 year window of competitive advantage where all other factors held constant.

Actionable Take-Aways

- The researchers proposed framework proved successful in both cases (ERP and cloud computing).

- The methodology – using publicly available information to estimate a rate of technology adoption between the stages – is simple and can be used by technology providers to predict when their technologies might go mainstream, allowing them to plan accordingly.

- Where accelerators advance a technology toward widespread adoption, as was the case with ERP just prior to Y2K, you should increase your estimate of stage advancement. For example, two units of SD instead of one.

- The same methodology can be used by technology buyers to estimate the period of competitive advantage they might gain by adopting a new technology in any of the first three stages of its adoption cycle (innovator-early adopter-early majority).

- Finance professionals might use the framework to assess investments in new technologies including net present value.

Cautionary Notes

- Many things impact and influence an organization’s success with a new technology deployment, including the firm’s competency to use and integrate the technology, its business and IT strategy, and its culture. Moreover, firms can’t predict how competitors might react or respond in individual cases.

- Technologies don’t always go through the hype cycle stages one after the other. Obviously, many new technologies fail. But even among those that ultimately succeed, some go though multiple hype cycles before finally breaking through to mainstream adoption.

- Though publicly-available and useful, Google Trends, Lexis-Nexis and WordCat reflect interest from the general population, not decision-makers in organizations. A more precise method might include information from firms themselves, such as in disclosures, annual reports and the like.

Q & A

-

Can you summarize your advice for firms deciding whether to adopt new technologies early?

One of the main messages of my research is that we need to be creative with our data. The study shows that we can use readily available data (e.g., google search, magazine articles, and book titles) as leading indicators of technology adoption. My recommendation to managers of firms that need to make adoption-related decisions is to look carefully at all the data they have and create their own leading indicators. To paraphrase a quote from Gary Klein (McKinsey article) they can gather information/create indicators to confirm what their gut is telling them.

2. Before a technology provider launches a technology, how can they use your framework to estimate when it might go mainstream?

Your question points to one of the limitations of this study. The sooner that you can make predictions is when you have already observed through your leading indicators the completion of one SD. Your prediction will be more accurate when you have observed two SD. So there is this trade-off between early prediction versus accurate prediction. This brings me back to my prior statement about using your leading technology indicators to validate what your experience/gut is telling you.

Additional questions? Please forward any questions you may have about this research to Dr. Theo Stratopoulos at: tstratopoulos@uwaterloo.ca.