A full copy of this paper can be obtained from the author, Dr. Greg Richins at the University of New South Wales, Sydney (g.richins@unsw.edu.au)

Introduction

Increasingly today, organizations strive to become “learning-centric.” Leaders encourage the formation of a culture of learning because continuous learning drives a host of benefits, including creativity, innovation, a defense against disruption and general performance improvements. Traditionally, firms have taken a direct approach to earning greater profits by focusing on productivity and performance goals, but this raises the concern that short-term gains may be had at the expense of longer-term benefits that come from creating a true culture of learning.

Within this context, the research summarized below investigates the effectiveness of learning goals, performance goals, and the combination of the two. Experimentation with the combination of learning and performance goals in conditions similar to those most workers encounter today make this paper unique.

Previous research demonstrates that the mere presence of performance goals distracts from and impairs learning. Thus, where learning is crucial, these studies would recommend separate learning goals should be assigned in the expectation that the resulting knowledge and skills gains will lead to better performance.

By contrast, this research finds that while learning goals (without performance goals) do improve learning and performance, performance goals (without learning goals) also improve performance, and equally well. When combined, however, learning and performance goals produce as much learning and better performance than either of the two in isolation. In combination with learning goals then, performance goals do not crowd out learning effort. Organizations can get the best of both worlds – improved learning, greater learning effort, and improved performance – by combining the goals.

Methodology

Past research demonstrates that goals should be made challenging. They should stretch an employee but not beyond their present capabilities. Past research also states that goals must be clear and specific (objective and easily measured) and relevant to the task at hand. For example, if a person needs new skills or knowledge to perform effectively in a task, then the manager should assign a learning goal. Past research also suggests that performance goals do not work well unless a person already has the skills and knowledge needed for the task. Again, this suggests that learning goals should be used first to encourage learning. Past research has not, however, observed what happens when you assign both goals simultaneously, or in sequence.

Prior to conducting his experiments, the researcher devised counting-related tasks and challenging, yet attainable goals related to the tasks. High performance could only be achieved by learning shortcuts to performing the work. In the short-term, participants could gain an advantage by focusing on performance alone. In the long term, however, time spent learning the shortcuts meant completing the tasks much faster. Complex tasks requiring learning and problem-solving were used because they represent the types of challenges workers regularly face in their jobs.

In all, 136 college students participated in two phases of the author’s experiments. They were paid a flat fee regardless of their performance. The author randomly assigned participants to four different experimental conditions in which they were given a learning or a performance goal; a learning and performance goal at the same time, or a learning goal followed by a performance goal. The author tested five hypotheses:

- Those given just a learning goal will learn more than participants assigned just a performance goal.

- Those assigned just a learning goal will perform as well but not better than participants given just a performance goal.

- Those given both learning and performance goals at the same time will learn less than participants only given a learning goal.

- Those given both learning and performance goals at the same time will perform no better in the long-term than participants given only a learning goal.

- Those given a learning goal first, then later on, a performance goal, will – in the long term – outperform participants given only a learning goal.

Results

- Those given just a learning goal spent more time looking for shortcuts than participants assigned just a performance goal. They also found slightly more shortcuts. In other words, consistent with the researchers first hypothesis, participants assigned learning goals learn more than those given performance goals. However, the difference in shortcuts found, while statistically significant, was marginal.

- Those assigned just a learning goal performed almost as well as participants given just a performance goal, but the difference was not statistically significant. The author reasons that participants who were given the performance goal tried harder – hard enough to offset any advantage learners acquired by discovering slightly more shortcuts.

- Among those given both learning and performance goals at the same time, the number of shortcuts found was virtually identical to the group given only a learning goal, even though the learning only group spent marginally more time looking for shortcuts (learning). The author’s hypothesis that dual goals would result in participants finding fewer shortcuts was not supported. Presence of the performance goal did not interfere with learning, if anything, it made the learning more efficient.

- Those given both learning and performance goals at the same time significantly outperformed those given only a learning goal. Combining learning and performance goals appears to drive better performance than learning goals alone. The author’s hypothesis that there would be no difference in performance between the two groups is not supported.

- Those given a learning goal first and later on, a performance goal, also significantly outperformed participants assigned only a learning goal. This supports the author’s 5th hypothesis.

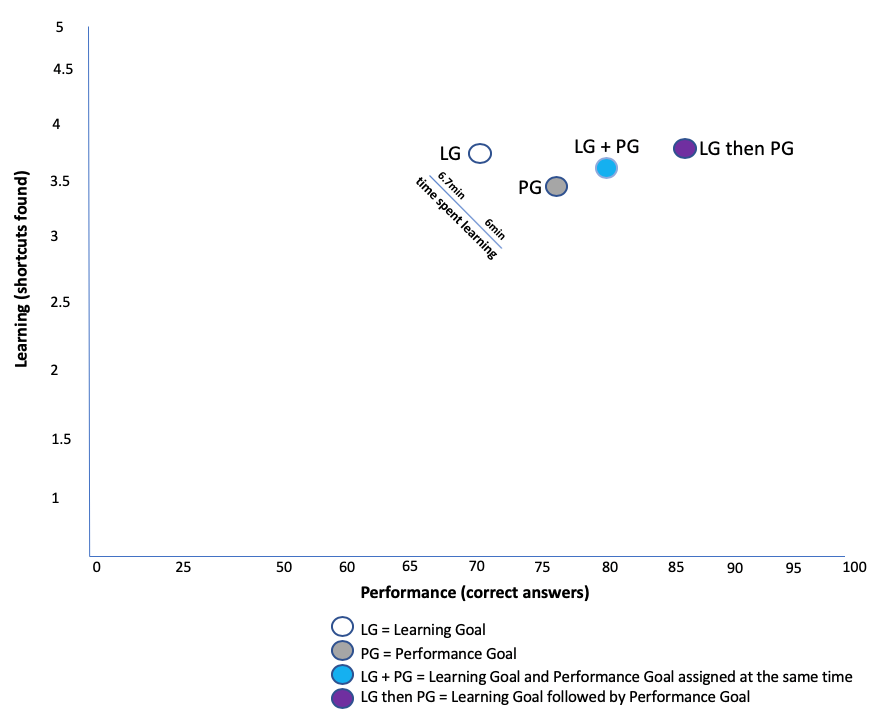

Figure 1: Combined goals exceed the benefits of solo learning or performance goals.

Takeaways

- Neither learning nor performance goals in isolation appear to generate substantially better performance. One can reasonably be used as a substitute for the other. Learners may learn more when challenged with learning goals but employees given performance goals will devote time to learning as well, and then apparently, work harder.

- Consider combining learning and performance goals either by assigning them at the same time or in sequence. Performance goals do not appear to interfere with learning when the two are combined, but the improvement in performance (over either of the two used separately) is significant (Figure 1).

- The author did not introduce rewards in this study. Beyond receiving a flat fee, participants could not earn extra by learning more or performing better. Future research will reveal what, if anything, changes after adding incentives.

Q & A

We asked the authors the following questions about their research.

-

Though the research might not have revealed this, under what circumstances do you think sequential, rather than simultaneous learning and performance goals, might work better, or vice versa?

I was a bit surprised to find that performance goals did not interfere with learning in the simultaneous condition. Given that, it's possible that sequential goals are not really needed. The one caveat to that is that although learning was about the same on average between my learning goal condition and my two combined goals conditions, I did find some evidence that there may be less variance in learning outcomes when you have just a learning goal. That being the case it may still make sense to not introduce performance goals until later for settings where the downside to someone not learning everything they're supposed to is really severe; e.g., training physicians.

2. Relative to what you’ve found about combining goals, how important is goal-crafting itself?

There are lots of different ways to set goals (manager assigned, self-set, jointly set, etc.) all of which can be viable in different circumstances. However, if you don't get it right in this stage, I don't think it will matter how goals are combined because if the underlying goals are bad, no method of combining them is going to fix that.

3. What would you hypothesize would change, if anything, if learning and/or performance contingent bonuses were added?

There are lots of different ways to set goals (manager assigned, self-set, jointly set, etc.) all of which can be viable in different circumstances. However, if you don't get it right in this stage, I don't think it will matter how goals are combined because if the underlying goals are bad, no method of combining them is going to fix that.

More questions? Please send any additional questions to the researchers: Dr. Greg Richins at: g.richins@unsw.edu.au.