I am a PhD student with the ECGG carrying out my doctoral research in Bali, Indonesia amidst the rich coral reefs and volcanic-formed beaches. Fieldwork has been a rewarding experience – often involving interviews in local fishing huts or beachside offices, and usually accompanied by strong Bali coffee and delicious local snacks of dried durian or sweet rice. My research examines how bridging organizations can be central actors in navigating the multi-sectoral, multi-scale setting of Bali’s coastal-marine systems, and in ways that can help to overcome the barriers and challenges of coastal-marine conservation.

The Indonesian province of Bali is located in the westernmost end of the Lesser Sunda Islands, located between Java to the west and Lombok to the east. Bali is also situated in the southwest corner of the Coral Triangle – a region home to the highest marine biodiversity on Earth. Bali is well known for its distinct Hindu culture and as a top tourism destination. Local peoples in the region are intimately linked to the sea as a source of livelihoods, food security and culture. Yet, options to conserve coastal-marine systems and sustain local livelihoods in Bali are constrained. As elsewhere, there is a critical need for coordination of numerous and diverse sets of actors to help advance conservation in a way that is more balanced in supporting regional level priorities while resonating with community values/concerns.

My research is situated within these complex settings and explores how the emergence of bridging organizations – i.e. independent entities that span the gaps between organizations (cf. Brown 1991) – can contribute to more effective multilevel governance of Bali’s coastal-marine systems. This research asks: how can regional and local-scale conservation actions be better connected? And how can the different systems of conservation practices (formal, informal), knowledge and beliefs be better integrated? It contributes to a growing body of scholarship on bridging organizations and environmental governance (e.g., Olsson et al. 2007; Berkes 2009; Rathwell and Peterson 2012; Alexander and Armitage 2014), and offers much desired empirical cases.

With the support of partners from Bogor Agricultural University, I have spent the last six months carrying out fieldwork in sites across Bali. To better understand bridging organizations and their constituent networks, I have focused on three cases: 1) the Nusa Penida Marine Protected Area (MPA), an island chain southeast off the Balinese coast where major livelihood activities are based on fisheries, seaweed production, and marine tourism; 2) the East Buleleng Conservation Zone in northern Bali, home to a series of long-standing local marine management areas and practices, and 3) the Bali MPA Network, a province-wide initiative to link organizations associated with freshwater and marine conservation. In each case I employ a mix of semi-structured interviews (n=108 to date) and social network analysis (SNA) to examine bridging organizations and the network of relationships that link them across space and time in the context of marine conservation.

What are some of my observations so far? First, bridging organizations have to deal with social diversity on two fronts – stemming from differences in the functions or interests of associations (e.g., tourism, marine enforcement, fisheries, funding and donors), and from the differences across scales and levels (local to national). Second, as its name typifies, a bridging organization ‘bridges’ or links different associations; however, the type of bridging tie (collaborative, communicative, financial) and the processes of bridging (via e.g., facilitating horizontal/vertical linkages, serving as conduits of ideas and brokers of resources) are variable between and within bridging organizations. Lastly, bridging organizations can catalyze shared visions and coordinate joint action; however, they also embody their own agendas and priorities. Critical reflection of how such agendas and priorities are promulgated via social networks is an important aspect of my ongoing analysis.

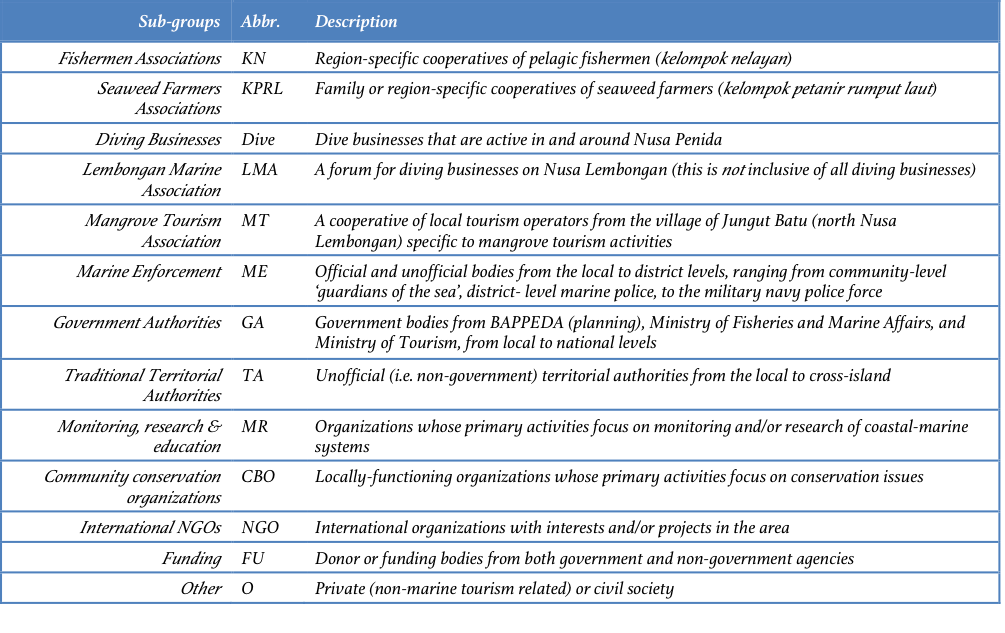

The Nusa Penida MPA illustrates some of these initial observations. Comprised of three major islands, the MPA covers 200km2 of coastal waters and contains a variety of critical marine ecosystems (including coral reefs, mangroves and sea grass beds) (Welly et al. 2011). It is home to some 47,000 residents who depend on fisheries, seaweed farming, and marine tourism for livelihoods. The MPA is the focus of a diversity of organizations (e.g., community groups, diving businesses, governments, fishermen and seaweed associations, etc.), which include subgroups with common functions or interests – see Table 1. Intensive utilization of coastal waters in the area by different (and competing) interests means the reality of coastal-marine conservation is remarkably complex and the potential for conflict is high.

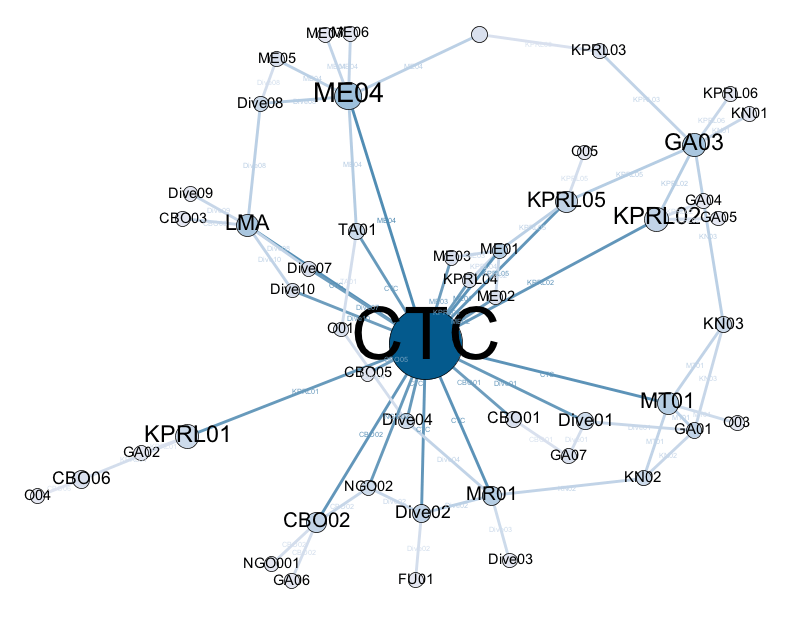

Working closely with the Nusa Penida MPA since 2008 is the Coral Triangle Center (CTC) – a locally based NGO that aims “…to inspire and train generations to care for coastal and marine ecosystems” by serving as a hub for the development and exchange of knowledge (CTC 2014). The CTC has emerged as a bridging organization to promote marine conservation and sustainable local livelihoods by overcoming the gaps between diverse organizations. The CTC is positioned to ‘bridge’ sets of actors with diverse economic, political and cultural interests that would otherwise not be connected. It does so by building different types of ‘ties’ or links between organizations, including: communication ties (where ties represent the sharing of knowledge or information exchange), collaboration ties (where ties represent joint projects, fieldwork, campaigns, monitoring, etc.), and, to a lesser extent, financial ties (where ties represent flow of resources – financial, in-kind or otherwise).

What does this mean for the Nusa Penida MPA? For starters, it gives a clear(er) understanding of: 1) the different sets of actors therein; 2) the structure/configuration of their interactions (or lack thereof); 3) the nature of such interactions; and 4) the role of a bridging organization in facilitating (or constraining) such interactions. Collectively, this information provides key insights on the governance of MPAs and MPA networks (see Alexander and Armitage 2014), which can inform future policy and practice. These are promising examples of the significance of bridging organizations in navigating the multi-sectoral, multi-scale setting of Bali’s coastal-marine systems. Yet, questions still remain. The remainder of my fieldwork will focus on clarifying and solidifying existing insights and patterns as they relate to bridging organizations, as well as gathering additional personal views and experiences of different constituent/stakeholder groups as appropriate.

The material and discussion presented here are not intended for reproduction or citation. Publications forthcoming. Questions or comments can be sent directly to Samantha at smberdej@uwaterloo.ca or on Twitter @sberdej.

This research is being carried out with the aid of a Doctoral Research Award from the International Development Research Centre (Ottawa, Canada), a Doctoral Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), and a SSHRC grant (to D. Armitage) on Coastal-Marine Transformations and Adaptive Governance. Supplementary support has been provided through the Community Conservation Research Network.

References:

Alexander, S.M. and D. Armitage. (2014). A social relational network perspective for MPA science. Conservation Letters doi: 10.1111/conl.12090

Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management 90:1692–1702.

Brown, L. D. (1991). Bridging organizations and sustainable development. Human Relations 44:807-831.

CTC – Coral Triangle Center (2014). Vision and mission. http://coraltrianglecenter.org/about-us/vision-and-mission/ Accessed: 01 April 2014.

Olsson, P., Folke, C., Galaz, V., Hahn, T. and L. Schulz. (2007). Enhancing the fit through adaptive co-management: creating and maintaining bridging functions for matching scales in the Kristianstads Vattenrike Biosphere Reserve, Sweden. Ecology and Society 12(1): 28.

Rathwell, K.J. and G.D. Peterson. (2012). Connecting social networks with ecosystem services for watershed governance: a social-ecological network perspective highlights the critical role of bridging organizations. Ecology and Society 17(2): 24.

Welly, M., W. Sanjaya, D. Trimudya and W.G. Yanto. (2011). Profil Perikanan Nusa Penida, Kabupaten Klungkung, Propinsi Bali. Pp. 28.