Regulating microplastic pollution: What we can learn from the European Union

By Nancy Goucher, Knowledge Mobilization Specialist, Water Institute

Externalized costs of microplastics

According to United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic currently entering the ocean annually will triple by the year 2040. Much of this plastic breaks down into microplastics, less than 5 millimeters in size. These tiny particles are accumulating not only in oceans, but in all the world’s ecosystems, from the highest mountains to the Arctic’s pristine wilderness.

Microplastics have been found in over 1,300 aquatic and terrestrial species, and extensively throughout the human body. The presence of microplastics in the food, air, and water we consume has generated concern over their potential health effects and wide-scale environmental harm. Microplastic pollution also has economic consequences. For example, marine natural capital loss is estimated to be between $3,300 and $33,000 per ton of plastic waste per year.

Given the known externalized costs of microplastics, the case for a whole-system approach to interventions is becoming clear. To be effective, policies must address the entire lifecycle of plastics, from extraction to remediation. Luckily, there are jurisdictions around the world beginning to implement a holistic policy framework.

Canada’s Plastic Policy Landscape

To date, Canada’s approach to regulating plastic pollution has been relatively narrow and focused on banning select sources of microplastic pollution. The primary framework for addressing plastic pollution is the Zero Plastic Waste Agenda(2018),which includes several key initiatives, most notably the Single-Use Plastic Ban. This 2022 ban restricts the sale of commonly littered items, such as plastic straws and bags. However, the policy is currently being challenged in court by major industry players including Dow Chemical, Imperial Oil, and Nova Chemicals, and could be overturned. Canada has also prohibited the sale of cosmetics containing microbeads since 2019.

Since the implementation of these measures, new research has shed light on the scale of microplastic emissions. We now know more about where microplastics are coming from and in what quantities. This new information can help guide the development of further policy actions that will more effectively mitigate the risks of microplastics to both the environment and public health.

Global Policy Dialogue on Microplastics

In March 2022, the UN Environment Assembly adopted a resolution recognizing the severe global impact of plastic pollution on the environment, society, and economy. It tasked UNEP with establishing a legally binding global plastics treaty by the end of 2024.

In the lead up to the final negotiating session for the treaty, several countries have been hosting webinars to deepen conversation and promote international cooperation. One such webinar, The Impact of Microplastic Pollution and the Role of the Plastics Treaty in the Future Policy Landscape, held on October 25, reviewed existing policy responses to microplastic pollution. The European Union’s approach to regulating microplastic pollution, could be particularly useful to other countries, including Canada, as they contemplate a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastics.

The EU’s Regulatory Framework

The EU has committed to reducing microplastic emissions by 30% by 2030 under its Zero Pollution Action Plan. This plan addresses two main categories of microplastic pollution: intentionally added microplastics and unintentionally released microplastics.

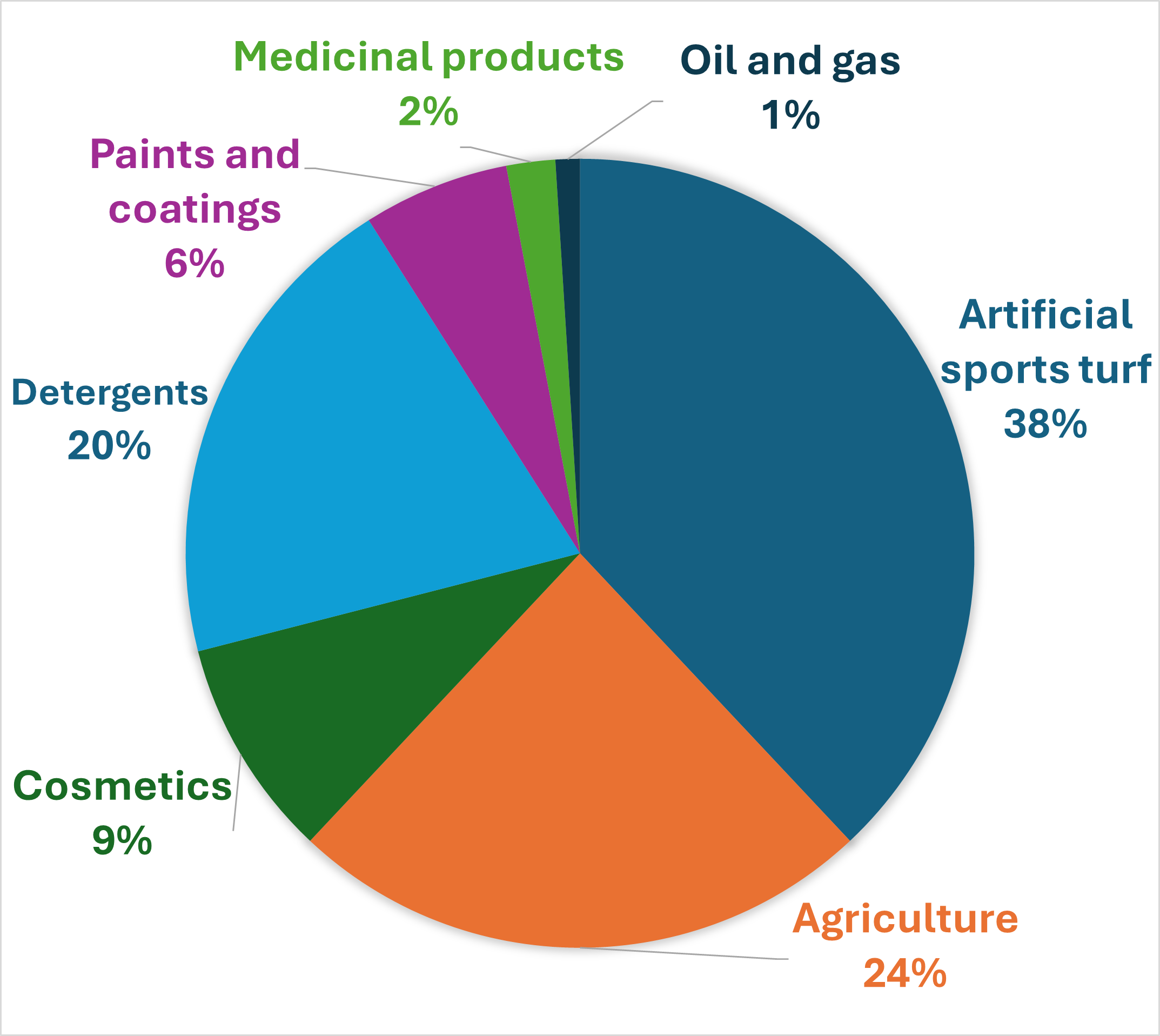

An estimated 42,000 tonnes of microplastics that are intentionally added to products are released into the environment every year in the EU. Current research suggests that the largest sources come from artificial sports turf (38 per cent), followed by agriculture (24 per cent) and detergents (20 per cent) (see Figure 1).

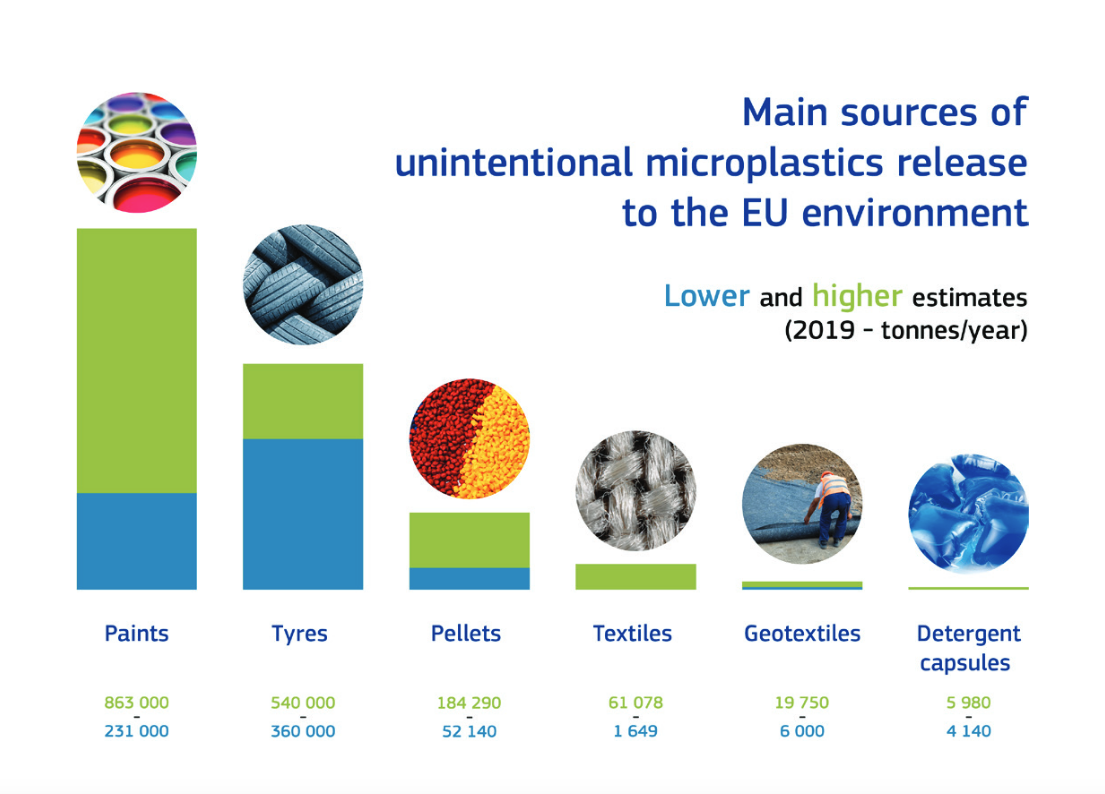

There are also many sources of microplastics that are unintentionally released into the EU environment. While more research is required to confirm estimates, studies conducted to date identify the largest sources to be paints, tires and pellets (see Figure 2).

The release of microplastics intentionally added to products

Figure 1: Annual release of intentionally-added microplastics into the environment by sector. Source: Hungarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, the European Commission, and The Pew Charitable Trusts (25 October, 2024). The Impact of Microplastic Pollution and the Role of the Plastics Treaty in the Future Policy Landscape. [PowerPoint Slides].

Figure 2: Sources of microplastics from unintentional releases in the EU. Source: https://effop.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/EU-Action-Against-Microplastics.pdf

Regulating Intentionally Added Microplastics

The EU has introduced new regulations to reduce the release of microplastics from products where plastic is intentionally added such as fertilizers, detergents, cosmetics, and paints. These regulations include phased bans, starting with microbeads, which were banned as of October 17, 2023. Other products will be phased out over time, with some restrictions coming into force by 2035. The phased approach allows manufacturers time to adjust and comply with new standards.

|

Date |

Ban on Products with Intentionally Added Microplastics |

|

October 17, 2023 |

|

|

October 17, 2027 |

|

|

October 17, 2028 |

|

|

October 17, 2029 |

|

|

October 17, 2031 |

|

|

October 17, 2035 |

|

Unintentional Microplastic Release

The EU has also focused on minimizing the unintentional release of microplastics, especially plastic pellets—the raw material used in plastic manufacturing. In 2019, an estimated 2,100 to 7,300 truckloads of plastic pellets were lost to the environment. To address this, the EU is working on policies to prevent, contain, and clean up these pellet emissions during transport and handling.

Next Steps: Strengthening Policy Frameworks

During the October 2024 webinar, experts suggested several strategies that could be included in the Global Plastic Treaty and/or adopted by individual countries to mitigate microplastic pollution. These include:

- Reduced plastic production – downstream activities such as improved waste management and removal technologies cannot sufficiently curb plastic pollution. Instead, we need to prioritize the reduction of Primary Plastic Polymers production using phase-down schedules and Global Aggregate Targets.

- Target plastic products with the highest pollution risk. Consider eliminating or significantly reducing production of high-risk products, when feasible. When elimination is not feasible, consider control measures that ensure responsible circulation.

- Create a sector-by-sector approach that considers how best to prevent, limit, and capture microplastic emissions from each sector. The approach should consider the entire life cycle of plastics (i.e., from extraction through disposal).

- Consider upstream measures such as those that address the design requirements of products. For example, invest in research to redesign products like textiles and vehicle tires with the goal of reducing shedding of fibers and microplastics.

Tackling microplastic pollution requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both intentional and unintentional sources across the full life cycle of plastics. The European Union’s progressive regulatory framework offers valuable lessons for other countries, including Canada, to refine their policies. By reducing plastic production, targeting high-risk products, and implementing sector-specific strategies, nations can better mitigate the widespread environmental and health impacts of microplastics. As the UN works toward a legally binding global plastics treaty, these insights can help shape more effective, coordinated action to combat microplastic pollution worldwide.

Banner photo: Detergent capsules by Marco Verch.