Scientists play a vital role in Global Plastics Treaty negotiations

By Cassandra Sherlock and Nancy Goucher

From April 23 to 29, the world came together in Ottawa for the global plastics treaty negotiations at INC-4 (the 4th session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee). The University of Waterloo, through the Water Institute, participated as an official observer. This involved sending a delegation to witness the negotiations at a pivotal moment in the collective goal of ending plastic pollution. The delegation consisted of members of the Microplastics Fingerprinting project, Stephanie Slowinski, Nancy Goucher, and Cassandra Sherlock, as well as Elizabeth Prince, Assistant Professor from the Department of Chemical Engineering.

INC-4 was a critical gathering, setting the stage for the final negotiations scheduled for November 2024 in Busan, South Korea. Observing the negotiations provided insight into how various issues are being considered, including primary plastic polymer production cuts, problematic plastic products, chemicals of concern, extended producer responsibility, and financial mechanisms to help transitioning countries reduce plastic usage. The negotiating rooms buzzed with the voices of stakeholders, representing diverse perspectives, and underscoring the importance of multilateral collaboration emphasized by INC-4 chair Luis Vayas Valdivieso, "Together we are stronger."

The role of science in exposing the plastic pollution crisis

Since plastic pollution was discovered in the 1960’s, scientific research has not only informed a policy response from numerous countries; it has also helped elevate the plastics agenda to an international level. During one of the side events at INC-4, Margaret Spring, Chief Conservation and Science Officer of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, explained how a several key reports created a sense of urgency around plastics. The growing level of concern compelled the United Nations Environment Assembly to call for the development of a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution in March 2022 through resolution 5/14.

Spring described how plastics science has been evolving quickly, which stimulated a relatively rapid policy response. The influential 2016 report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern, included a chapter outlining the detrimental impacts of macro- and microplastics on the environment globally. Only six years later - due to an explosion of literature on the issue - UNEP released an update, From Pollution to Solution. This report drew attention to the magnitude and severity of the plastic pollution crisis, and particularly the impacts on human health. The connection that scientists made between plastic pollution and human health helped drive the need for global solutions.

In addition to highlighting the potential harm of plastics, scientists have also had a role in identifying sustainable paths forward. At another INC-4 side event hosted by the University of Plymouth, the discussion focused on whether viable alternatives and substitutes to plastics exist and if this could and should be part of the solution. The scientists on the panel generally agreed that transiting to new materials would be an insufficient solution unless the unintended environmental, societal, and economic consequences of the alternatives are accounted for in the appropriate contexts. This would need to be assessed through product testing and life cycle assessments.

The importance of the scientific voice during the treaty negotiations

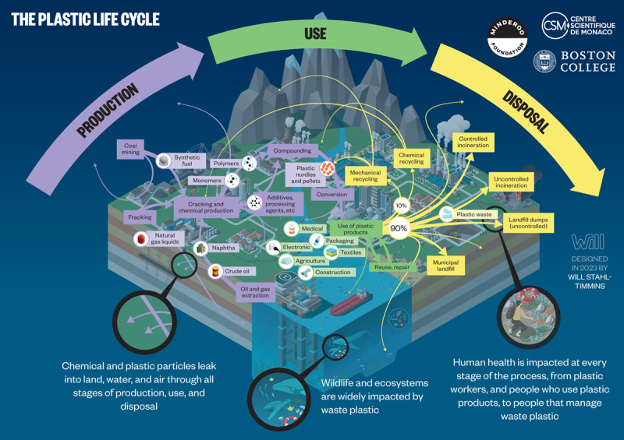

When UNEA passed resolution 5/14, they were clear in their direction that countries should develop an instrument to address the full life cycle of plastic. This has been interpreted to mean considering the full scope of challenges posed by plastics, from extraction to disposal. Spring noted this to be another example where science has informed the scope of the treaty. In particular, the report, Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health emphasized the harms of plastic – on the environment, economy, and social inequities - occur at every stage of the plastic life cycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The plastic life cycle spans three major phases: production, use and disposal. Plastics are utilized in multiple sectors and provide many benefits. However, this comes with a vast array of unintended consequences throughout the lifecycle, such as environmental leakage of chemicals, impacts on wildlife and human health hazards.

Another topic in the treaty being negotiated relates to the chemical composition of plastics, which can affect the toxicity of plastic pollution and impact recycling efforts. Here, scientists alerted the public to the severity of the issue and potential solutions including through the PlastChem report released in March 2024. The lead author, Dr. Martin Wagner identifies more than 16,000 chemicals used in the plastic manufacturing process; 26% of which are considered to be ‘highly hazardous’ to human health and the environment. The report calls for transparency and better management of chemicals of concern in plastic, stating that innovations in plastic are needed to support safety, sustainability, and necessity rather than just functionality. The report calls on the treaty to consider the scientific evidence when considering plastic production moving forward.

To ensure the treaty retains a comprehensive scope focused on the full life cycle approach, a group of independent scientific and technical experts have formed the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty. The coalition is actively contributing to the treaty process by providing concise summaries and expert interpretations of scientific knowledge, including through fact sheets and policy briefs. During the negotiation sessions, we heard delegates reference some of these materials, demonstrating the importance of providing real time scientific advice. The Scientists’ Coalition has also been taking proactive steps to correct any misinformation included in formal statements from participating nations. They have also been pointing out cases where strong scientific evidence exists to support the development a strong and effective treaty.

How we’re engaged through the Microplastics Fingerprinting project

While the research we are doing in the Microplastics Fingerprinting project is not directly informing the plastics treaty negotiations, our team believes these global discussions offer a unique opportunity for us to support efforts focused on reducing or eliminating the harms of plastic pollution.

As our research has progressed, a wide range of stakeholders have been interested in what we’ve been learning about the sources, transport and fate of plastic pollution. For example, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada, Steven Guilbeault, invited the UW delegation to a private roundtable event during INC-4. Here, we had the opportunity to share our scientific insights on the treaty with Minister Guilbeault and his staff. This experience is a great example of how the engagement of scientists in the policy making process can be helpful in supporting evidence-based decision making.

The University of Waterloo’s delegation walked away from INC-4 feeling inspired by the role that science has played in the treaty so far. As the delegates finalize the details of the treaty over the next few months, we encourage them to draw from the large body of scientific evidence around plastic pollution that clearly calls for a change in status quo.

Photo caption: The University of Waterloo delegation at INC-4: Professor Elisabeth Prince, Nancy Goucher, Stephanie Slowinski, and Cassandra Sherlock.