Siege of Orleans Execution of Joan Fall of Rouen Battle of Castillon

The Siege of Orleans

12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429

(1.2a-c, 1.4a-c, 1.5a, 1.6a, 2.1a-b, 2.2a; The Rise of Joan of Arc)

Melvin Bragg on the Siege of Orleans, BBC Radio 4

Excerpted from Rickard, J (18 January 2011), Siege of Orleans, 4 February-March 1563, http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/siege_orleans_1563.html

The siege of Orleans (4 February-March 1563) was the last major military action of the First War of Religion, and ended after the assassination of Duke François of Guise, the last major Catholic leader in the field.

Guise had become the sole Catholic leader as a result of the battle of Dreux (19 December 1562). Although this had been a Catholic victory two of their leaders had been lost - Anne, duke of Montmorency having been captured and Marshal Saint-André captured and then murdered. On the Huguenot side the Prince of Condé had also been captured, leaving Admiral Coligny as the main Protestant commander.

In the aftermath of the battle Coligny retreated to the main Huguenot stronghold at Orleans, before on 1 February leaving the city with his German cavalry. François d'Andelot was left to command the defence of the city.

The duke of Guise reached Orleans on 4 February, and the siege began on the following day. On 6 February the Catholics had their first major success. The main city of Orleans, on the north bank of the Loire, was connected by a bridge to the suburb of Portereau on the southern bank. The suburb had weaker defences than the main city, but its walls were protected by two bastions, one garrisoned by Gascon infantry and the other by German infantry. Guise sent his main army to make a feint against the bastion held by the Gascons, while a small force captured the other bastion. The suburb was quickly in Catholic hands, and the defenders only just prevented them from crossing the bridge into he main part of the city.

The siege was noteworthy for one of the first uses of brass shells in warfare. The English Ambassador, Sir Thomas Smith, who was observing the siege with the Royal court at Blois, recorded his impressions in a letter to the Privy Council -

'I have learned this day, the fifteenth instant, of the Spaniards, that they of Orleans shoot brass which is hollow, and so devised within that when it falls it opens and breaks into many pieces with a great fire, and hurts and kills all who are around it. Which is a new device and very terrible, for it pierces the house first, and breaks at the last rebound. Every man in Portereau is fain to run away, they cannot tell whither, when they see where the shot falls'.

The nature of the siege, and of the entire war, changed dramatically on 18 February. The Royal siege works had progressed to the point where Guise was planning to launch an attack on the city on 19 February, and on the evening of the 18th he visited the works to inspect them. On his way back from this inspection he was shot and mortally wounded by a man on horseback. The assassin initially made his escape, but was later arrested when he became lost in the dark. The assassin, Jean Poltrot, lord of Mérey in Angoumois, was motivated by a desire to get revenge for Guise's persecution of the Huguenots. He was eventually executed for his crime, but outlived Guise, who died on 24 February 1563.

The death of Guise left Catherine de Medici free to begin peace negotiations. On 8 March the prince of Condé and the duke of Montmorency were both released, and a peace began on the same day. The basis of the Edict of Amboise was agreed on 12 March, and the treaty was signed by Condé on 18 March. The Huguenots won a limited amount of legal toleration, and four years of peace followed before the outbreak of the Second War of Religion.

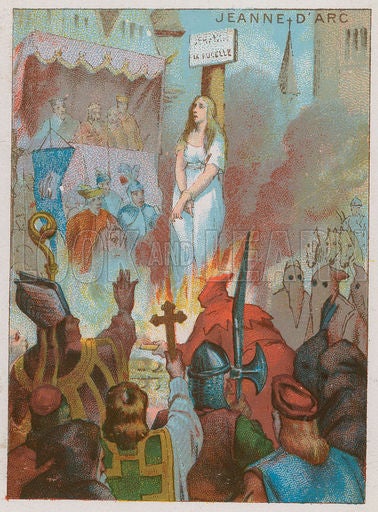

The Execution of Joan la Pucelle

30 May 1431

(5.5a-c, historically in Rouen, but in Anjou in Shakespeare)

Solved at last: the Burning Mystery of Joan of Arc

Excerpted from Joan of Arc - Facts and Summary. http://www.history.com/topics/saint-joan-of-arc

After such a miraculous victory, Joan’s reputation spread far and wide among French forces. She and her followers escorted Charles across enemy territory to Reims, taking towns that resisted by force and enabling his coronation as King Charles VII in July 1429. Joan argued that the French should press their advantage with an attempt to retake Paris, but Charles wavered, even as his favorite at court, Georges de La Trémoille, warned him that Joan was becoming too powerful. The Anglo-Burgundians were able to fortify their positions in Paris, and turned back an attack led by Joan in September.

In the spring of 1430, the king ordered Joan to confront a Burgundian assault on Compiégne. In her effort to defend the town and its inhabitants, she was thrown from her horse, and was left outside the town’s gates as they closed. The Burgundians took her captive, and brought her amid much fanfare to the castle of Bouvreuil, occupied by the English commander at Rouen.

In the trial that followed, Joan was ordered to answer to some 70 charges against her, including witchcraft, heresy and dressing like a man. The Anglo-Burgundians were aiming to get rid of the young leader as well as discredit Charles, who owed his coronation to her. In attempting to distance himself from an accused heretic and witch, the French king made no attempt to negotiate Joan’s release.

In May 1431, after a year in captivity and under threat of death, Joan relented and signed a confession denying that she had ever received divine guidance. Several days later, however, she defied orders by again donning men’s clothes, and authorities pronounced her death sentence. On the morning of May 30, at the age of 19, Joan was taken to the old market place of Rouen and burned at the stake. Her fame only increased after her death, however, and 20 years later a new trial ordered by Charles VII cleared her name. Long before Pope Benedict XV canonized her in 1920, Joan of Arc had attained mythic stature, inspiring numerous works of art and literature over the centuries and becoming the patron saint of France.

The Fall of Rouen

29 October 1449

(3.2a-e, 3.3a; French re-take English territory)

THE FALL OF ROUEN

Excerpted from Nicholle, David. The Fall of English France 1449-53 (Campaign). Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2012.

A well-coordinated assault by Charles VII and François I now reconquered much of Normandy in less than a year, largely because the English were hopelessly unprepared but also because the majority of the Norman population supported the French cause. Although the Duke of Burgundy was preoccupied with a rebellion in Flanders, the French were reportedly strengthened by some Burgundian troops while several French compagnies were redeployed from peacetime locations in the south, including some of Charles VII’s foreign forces. This French campaign was conducted by four separate armies, the first success being achieved by Pierre de Brézé, who seized the vital town of Verneuil on 19 July 1449. The place was supposedly betrayed by a local militiaman whom the English had beaten for sleeping at his post. On 6 August King Charles VII himself crossed the river Loire to take command, eventually joining forces with the army led by Jean de Dunois. On 8 August the French took Pont-Audemer and hardly a week then seemed to pass without another major English-held town or castle falling. On 26 August the inhabitants of Mantes forced the English garrison to surrender by seizing control of a tower and gate. Around the same time, Roche-Guyon was reportedly surrendered by its captain in exchange for an assurance that he could keep the lands of his French wife. In September, the Duke of Brittany formally handed over to King Charles VII’s representative all those places the Breton army had captured in western Normandy. Meanwhile, in southern Normandy the Duke of Alençon seized the major fortified city of Alençon, which had been beyond his control for decades. On 13 October there was a procession of children through Paris to give thanks for these astonishing victories, though the campaign was certainly not over. Three days later Charles VII and Dunois besieged the Norman capital of Rouen, which fell in less than a week. Here the English fought hard but not for long, the inhabitants being divided, some sending a deputation to England begging for support while others insisting that the garrison surrender. Edmund Beaufort was in overall command and agreed to negotiate. Realizing that no help could arrive from England in time, he agreed to surrender. His more belligerent subordinate, Talbot, was one of eight hostages handed over to the French while Beaufort and the garrison were allowed to march to English-held Caen.

The Siege of Bordeaux/The Battle of Castillon

17 July 1453

(4.5a, 4.6a; the Death of Talbot)

THE LOSS OF GUIENNE: The End of the Hundred Years' War

Excerpted from Oman, C. History of England from the Accession of Richard II to the Death of Richard III. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1906. 358-360.

"The

fate

of

Guienne

was

at

this

moment

in

the

balance.

In

1451 Charles

VII had

turned

his

victorious

arms

from

Normandy

to

the

south.

The

Bastard

of

Orleans

had

captured

one

after

another

the

outlying

bulwarks

of

Bordeaux;

Bourg

and

Blaye

had

fallen

in

May,

Fronsac

and

Libourne

early

in

June.

No

succours

arrived

from

England,

where

the

parliamentary

struggle

of

1451

was

then

at

its

height,

and

on

June

30

the

inhabitants

of

Bordeaux,

with

manifest

reluctance,

surrendered

their

city.

On

August

20

Bayonne,

the

last

fortress

where

the

English

banner

flew,

had

opened

its

gates,

and

the

subjection

of

Guienne

seemed

complete.

"But

provincial

independence

was

dear

to

the

Guiennois;

they

were

loyal

in

their

hearts

to Henry

VI,

and

they

chafed

bitterly

against

the

new

taxes

and

the

abrogation

of

old

customs

which

the

French

conquest

brought

about.

Within

six

months

of

the

fall

of

Bayonne

Gascon

nobles

and

burghers

were

visiting

London

in

secret,

to

pledge

their

faith

that

the

whole

province

would

rise

in

arms

the

moment

that

an

English

army

showed

itself

on

the

Gironde.

When

the

appeal

was

made

to

him

not

to

wreck

this

fair

chance

of

resuming

the

struggle

with

France,

York

[Richard,

Duke

of

York],

as

the

advocate

of

a

vigorous

war

policy,

could

hardly

refuse

his

aid.

He

consented,

and

a

great

effort

was

made

to

raise

an

army

for

the

invasion

of

Guienne.

In

July,

1452,

the

veteran Talbot,

who

had

been

created

Earl

of

Shrewsbury

some

years

before,

was

commissioned

to

raise

3,000

men

for

that

enterprise.

"The

struggle

of York and Somerset was

suspended

for

a

year

and

more,

while

both

parties

gave

their

aid

for

this

attempt

to

rescue

the

last

remnant

of

the

English

dominion

in

France.

Talbot

landed

on

October

17

in

the

Médoc;

on

the

21st

the

Bordelais

threw

open

their

gates

to

him.

Within

a

few

weeks

most

of

the

places

around

the

great

city

were

once

more

English.

Then

came

winter,

and

nearly

six

months

of

respite

before

the

slow-moving

Charles

of

France

launched

his

armies

against

Guienne.

By

this

time

Talbot

had

received

reinforcements

from

England

under

his

son

Lord

Lisle;

with

their

aid

he

won

back

Fronsac,

which

all

through

the

reign

of

Henry

VI

had

been

the

frontier

fortress

of

the

English

territory

in

Guienne.

It

was

only

in

July,

1453,

that

the

French

appeared,

in

overwhelming

force,

and

laid

siege

to

Castillon

on

the

Dordogne.

"Talbot

marched

out

to

its

relief,

with

every

man,

Gascon

and

English,

that

he

could

collect.

On

the

17th

he

fell

furiously

upon

the

besiegers,

who

were

stockaded

in

a

great

entrenched

camp.

So

well

were

they

covered

that

the

old

earl

did

not

see

how

he

could

turn

his

archery,

the

real

strength

of

his

army,

to

any

account.

Forming

his

whole

force

into

a

dense

column,

with

the

men-at-arms

at

the

head,

he

marched

straight

at

the

trenches.

Though

torn

to

pieces

by

the

French

artillery,

the

assailants

crossed

the

ditch,

and

strove

time

after

time

to

force

their

way

into

the

lines.

They

were

repelled,

and

presently

outlying

contingents

from

other

parts

of

the

circumvallation

came

up,

and

began

to

take

the

English

in

flank

and

rear.

At

this

moment

Talbot

was

struck

down

by

a

cannon

ball,

which

broke

his

leg.

His

sons

and

his

body-squires

fought

fiercely

in

his

defence,

but

were

slain

one

after

another.

The

French

sallied

out

of

their

trenches,

the

English

column

broke

up,

and

all

was

lost.

Talbot

and

Lisle

were

found

dead

side

by

side,

and

all

the

flower

of

their

host

had

perished.

"Nothing

can

show

better

the

loyalty

of

the

Guiennois

to

the

English

cause

than

the

fact

that

many

of

the

smaller

towns

held

out

for

two

months

after

the

disaster

at

Castillon,

and

that

Bordeaux

itself,

though

hopeless

of

succour,

did

not

surrender

till

October

19,

after

it

had

stood

a

siege

of

eighty

days.

But

this

was

the

end;

the

French

king

took

good

care

that

his

new

subjects

should

not

have

another

chance

to

rebel,

and

England

for

twenty

years

was

in

no

condition

to

think

of

sending

an

army

overseas.

Yet

the

remembrance

of

their

old

connexion

with

the

island

realm

long

remained

deep

in

the

breasts

of

the

men

of

Bordeaux;

not

only

in

the

days

of Edward

IV,

but

so

late

as

those

of Henry

VIII,

secret

messages

were

sent

to

England

from

the

Gironde,

and

a

vigorous

attempt

to

recover

Guienne

might

yet

have

found

aid

from

within.

Fortunately

for

both

parties

the

attempt

was

never

made.