About | Daramturgy Hub |

‘All the Pretty Little Horses’ - A Lament to the Abandoned Babe

by Emily Radcliffe

The lyrics to the ominous lullaby sung during this production of Portia’s Julius Caesar, “All the Pretty Little Horses” holds a story with a mysterious and heart-wrenching past. The lyrics as we know them from this production are as follows:

Hush-a-bye

Don’t you cry

Go to sleep my little baby

When you wake

You shall have

All the pretty little horses

(repeat)

Dapples and Greys

Pintos and Bays

All the pretty little horses

(repeat)

Way down yonder

In the meadow

Poor little baby crying ‘Mama!’

Bees and the Butterflies

Pecking out his eyes

Poor little baby crying “Mama!”

Upon researching the origins of this song, it became evident to me that this song was known to be sung by African-American “Mammies” in southern plantations in the United States. Dorothy Scarborough retells a nearly identical song sung by Black “Mammies” and enslaved people on plantations from generations before 1925, when this book was written:

Hushaby

And don’t you cry,

My sweet, pretty little baby.

When you wake, you and shall have cake,

And oh, the pretty little horses.

Four little ponies you shall have,

All the pretty little ponies,

White and gray, black and bay,

Oh, the pretty little horses. (Scarborough 146)

And similarly…

Go to sleepy, little baby,

Go to sleepy, little baby.

Mammy and daddy have both gone away

And left nobody for to mind you.

So rockaby,

And don’t you cry.

And go to sleepy, little baby.

And when you wake

You can ride

All the pretty little ponies.

Paint and bay,

Sorrel and a gray,

And all the pretty little ponies.

So go to sleepy, little baby.

Rockaby

And don’t you cry

And go to sleep, my baby. (146)

And added from another variant…

’Way down yonder

In de meadow

There’s a po’ little lambie.

The bees and the butterflies

Peckin’ out its eyes.

Po’ li’l thing cried, Mammy! (148)

In their recount of these songs, this author comments on how “rather melancholy and depressing” these lullabies are – attributing it to the Black caretakers’ lack of knowledge in infantile complexes of sleep and nightmares (148). However, unconsidered by the writer was the daily traumatic reality of these enslaved women who were not only forced to take care of their white masters’ children, as they would their own, but many were also forced to leave their own children behind and in the care of others, or these children were sold and shipped off elsewhere (Scarborough 144-5). Although, Scarborough does share the insight to clarify that not every song sung by Black “Mammies” were intended for the white children they cared for – but that songs like these were distinctly expressive of a mother’s heart aching love for her own child (153).

Upon reflection of this history, I was able to connect the sentiment of this lullaby to part of my own heritage – specifically part of my maternal grandmother’s history. In January of 1981, my grandmother Margaret, and at the time, mother to 5 children, migrated alone from the island of Barbados to wintery Ontario, Canada. The objective of her mission was in search of a better life for her kids. In order to make enough money to bring her children to Canada with her, she had to work as a full-time, live-in nanny for a few different White-Jewish families in Hamilton and Toronto. Taking care of the children of these families and raising them as she would her own, came with many challenges. But one of the most constant challenges faced was thinking of her children back home in Barbados. She explained to me that she would often cry at the very thought of them. I can only imagine the heartache of sensing the cries of your children, longing for your presence and comfort, while you must take care of other children in a distant land.

These lullabies manage to capture the constant and anxious awareness of that faraway child, who, in the mind of their mother, is constantly and helplessly crying out for them in their absence. What these songs are able to capture is the singer’s attempt to telepathically sooth the innate concerns of their child and but also sooth their own heart, with the promise of reuniting and giving them “all the pretty little horses.”

References

Cowling, Camillia, et al. “Mothering Slaves: Comparative Perspectives on Motherhood, Childlessness, and the Care of Children in Atlantic Slave Societies.” Slavery & Abolition, vol. 38, no. 2, 2017, pp. 223–231., https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039x.2017.1316959.

Scarborough, Dorothy. “On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs.” Internet Archive, Cambridge, [Mass.] : Harvard University Press, 1925, 19 Jan. 2012, https://archive.org/details/ontrailofnegrofo00scar/page/148/mode/2up.

Breastfeeding – A Divine Power or Uncivilized Burden?

by Emily Radcliffe

Expectations of a

Roman Noblewoman

In the patriarchal ancient Rome, the role of a Noblewomen was viewed as significant just as it was insignificant. The Noblewoman did not have much formal decision-making power when it came to public order. However, her role toward the success of her household was where most of her influence lay. After marriage and bearing legitimate child(ren) to her husband, she was to preserve the honour of their house. She should educate her child(ren), watch over the family affairs, and lead her life in a way that upholds the dignity and respect she shares with her husband (Smith 744; Challet 376; Lefkowitz and Fant 41). As absolute as this sounds, the Noble wife and mother still held a small measure of choice regarding one major element of nurturing a child in its infancy – breastfeeding. Although, the surrounding conditions of this “choice” made it seem like breastfeeding one’s own child should not be much of a choice at all. Despite the private and intimate nature of this action between a mother and child – it was a rather taboo yet scarcely depicted ordeal, that was still somehow heavily influenced by public belief systems, male commentary, and external surveillance.

The Uncivilized Burden

Part of the perspective of breastfeeding being viewed with a doubtful gaze, can be attributed to ancient Romans viewing this practice as animalistic and barbaric (Koloski-Ostrow 185). Those who breastfed were those who could not afford to pay or enslave someone else to do it for them. But why would someone delegate this task, you ask? To ancient Roman women, there was a myriad of reasons. One being the physical tax – not just lack of sleep – but to avoid the perceived premature-aging or “uglifying” process that affects the appearance of the Noblewomen’s breast (Challet 375; Lefkowitz and Fant 41). Greek physician Soranus mentioned how among the class of women where appearance mattered, women opted not to threaten their beauty by opening themselves to the wear and tear of breastfeeding (Challet 375). With this emphasis on body image, the use of a wet nurse also acted as a symbol of wealth and status – a way to advertise the high position of their household (376).

Another reason was the desire to return to their esteemed social life and “wifely duties” as soon as possible (Koloski-Ostrow 194; Challet 376). In addition to the duties previously mentioned, a Noblewoman’s sexual loyalty to her husband was another determining factor. The belief was – that sexual intercourse both tainted and diminished the supply of breastmilk for the young child, and so in order to resume top-quality sexual activity with their spouse, after the birth of child, they should delegate this duty to a wetnurse (who was not permitted to engage in sexual activity for this reason). Additionally, in this patriarchal society, where a husband was often away and occupied with matters of politics and war, when he was home, avoiding more time apart helped to minimize considerable loneliness (376; Lefkowitz and Fant 12). On a more sombre note, another incentive to evading breastfeeding, as Keith R. Bradley theorizes, was to create affective distance between the parents and child, to avoid the emotional damage if the child dies. Although morbid to fathom, 1 of 4 infants did not live past their first birthday in ancient Rome, and of those, only half made it past their tenth birthday (374).

The divine power

On the other side of this debate is the idea of breastfeeding being an embrace of power and personal autonomy in a patriarchal society that, to this day, tries to limit it. On a natural level, the act of breastfeeding carries great physical and emotional benefit for both the participating mother and child - recording a shared sense of “closeness, security, and intense satisfaction” between them (Challet 373). On a supernatural level, a mother’s demonstration of such self-autonomy and exclusive, specific, and direct knowledge has been viewed as a demonstration of her demiurgic power – an autonomy responsible for the creation of the universe (Challet 378).

In Greek and Roman religious depictions, a nursing goddess’ breastmilk was believed to hold magical capabilities – wielding a power that can transfer divinity or protection, at her will (Koloski-Ostrow 187). Her image, bare-breasted and partially naked, represented the power to either cause destruction or grant protection in the face of evil and danger (187). This same state of nakedness for mortal women, however, was not held in equal light – as with the mortal woman, nudity was purely a sign of vulnerability.

But not all Romans believed this sense of life-giving power and personal strength was reserved for the gods and goddesses alike. Favorinus, a Roman philosopher from the 2nd century A.D. describes why breastfeeding should be performed by the mother of a newborn child – especially Noblewomen. Although articulated a couple centuries after Portia’s time, I am sure she would find great reassurance in his remarks:

‘I pray you, woman, let her be completely the mother of her own child. What sort of half-baked, unnatural kind of mother bears a child and then sends it away? To have nourished in her womb with her own blood something she could not see, and now that she can see it to feed it with her own milk, now that it’s alive and human, crying for its mother’s attentions? Or do you think’, he said, ‘that women have nipples for decoration and not for feeding their babies?’ […] ‘Why in heaven’s name corrupt that nobility of body and mind of the newborn human being, which was off to a fine start, with the alien and degraded food of the milk of a stranger?’ (Lefkowitz and Fant 189; Beerden and Naerebout 764-5).

References

Beerden, Kim, And Frederick G. Naerebout. “Roman Breastfeeding? Some Thoughts on a Funerary Altar in Florence.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 2, 2011, pp. 761–766., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0009838811000218.

Challet, Claude-Emmanuelle Centlivres. “Roman Breastfeeding: Control and Affect.” Arethusa, vol. 50, no. 3, 2017, pp. 369–384., https://doi.org/10.1353/are.2017.0013.

Koloski-Ostrow, Ann Olga, et al. “Nursing Mothers In Classical Art.” Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology, Routledge, 1998, pp. 174–196. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/10.4324/9780203037713

Lefkowitz, Mary R., and Maureen B. Fant. Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

Murray, John. “Matrimonium.” LacusCurtius • Roman Marriage - Matrimonium (Smith's Dictionary, 1875), https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Matrimonium.html#customs.

“She Owns a House? Is She Allowed to do That?”… Property Law in the Roman Republic

by Anna Whitehead

There are two scenes in Portia’s Julius Caesar that take place at Servilia’s house. The general assumption might be that women were not allowed to own property in the Roman Republic and yet there is a location referred to as “Servilia’s House” in this play. Does this refer to a house she legally owned or did she simply live there? All her close male relatives were dead, is it possible that the legal owner of the house is Servilia?

Patria Potestas (Paternal Power)

In the Roman Republic, all children (male and female) were under the power of their fathers, during their father’s lifetime. This meant that any money or property that children inherited or acquired belonged to their father (Shelton). Upon the death of their father, children became free and under their own power. A father could also choose to use a legal act to free a child (Treggiari, “Servilia”). Early in the Roman Republic, when a woman married, she transferred to being under the power of her husband rather than her father, but by the time of the late Republic, this practice seems to have died out (Treggiari, “Servilia”). Once their father was dead, children became sui iuris (independent) and could own land, have their own money, and sons could have power over their children (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

Servilia’s father was dead by the time she was nine years old, meaning she was sui iuris from the time of his death until her own death (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

Dowries

Dowries in the Roman Republic were money or property that a woman brought to a marriage that was meant to support her for the remainder of the marriage. During the wedding ceremony, a dotal contract might be agreed upon to decide what would happen to the bride’s dowry at the end of the marriage (Treggiari, “Marriage”). This would include both divorce and death scenarios and would be legally binding if either of these events came to pass. If a woman died and she was still under the ownership of her father, her dowry would revert to him. If her father had died it might go to her mother or brother. If the marriage ended by divorce, the woman or her father had the right to sue for the return of her dowry. If the woman was found morally wanting in the case of a divorce, her husband could keep one-sixth of her dowry for each of their children to inherit, this included female children. If the man was found morally wanting in the case of divorce, he had to return her dowry immediately. This means that women could acquire property through their own divorces, or the divorce or death of their daughters (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

Servilia’s status as sui iuris meant she would have maintained ownership of her lands and wealth during both of her marriages. Only her dowry would have been given to her husband (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

Female Ownership of Property

Married women were perfectly within their rights to own land, separate from that of their husbands. During her affair with Julius Caesar, the historical Servilia was given the opportunity to buy several pieces of land at a significantly discounted price (Treggiari, “Servilia”). The expectation was that a woman would leave her land and other property to her children after her death, but it was in her control, and she could bequeath it to whomever she chose. Daughters had equal claim to their parents’ estate, and could inherit land as a son would. However, a daughter might receive less inheritance than her brother, as her dowry might be considered part of her inheritance. A son might also inherit less from the family estate if his parents helped to fund his political career or similar. The Voconian Law of 169 A.D. prevented testators from making a woman their heir but they could leave her a substantial amount of money or land; through a loophole in this law, property could also be left in trust to women. (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

Servilia would have been a very wealthy woman. She quite possibly received large inheritances from her father, her mother, her brother, both husbands, and other extended family members. It is not certain exactly what land she owned but there is evidence to suggest that she owned farms, coastal villas, several houses, and even some parks or gardens (Treggiari, “Servilia”).

References

Shelton, Jo-Ann, and Pauline Ripat. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Treggiari, Susan. Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian / Susan Treggiari. Clarendon Press, 1993.

Treggiari, Susan. Servilia and Her Family. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Significant Meanings of Fire in Ancient Rome

by Paula Bornacelli

In North America, putting your index and middle finger up is given the name ‘peace sign,’ an adopted symbol from anti-war activists to signify peace (Anderson). Did you know that the same sign in North America, if done with the palm facing inward, in countries such as England and Ireland is a sign of disrespect, “like flipping someone off” (Forbes). There are many gestures or objects around the world that are used to symbolize different ideas, and this was no different in Ancient Rome. Currently, in contemporary North America, there are many different ideas of what fire symbolizes; for example, it can signify wisdom, transformation, or freedom, but in ancient Rome, fire had different meanings.

In Portia’s Julius Caesar fire becomes significant by the end of the play, as it creates a backdrop for momentous changes in the lives of the play’s central characters. Understanding what fire meant to the Romans in 44 B.C. can offer insight into the central question of the play, and further our understanding of why the playwright, Kaitlyn Riordan, chose to use fire in her approach to adapting the story of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

In ancient Rome, fire was seen as a destructive force, but it also contained a quality of purification. Fire was used as an element for magical purification rites; it was associated with a masculine approach to life, and it was characterized as being both helpful and destructive by its respective Roman Gods, Vesta and Vulcan.

Vesta is described as the God of hearth, home and domestic life and is rarely depicted as a woman but rather as fire (Geller). This fire was contained within a temple of worship that was tended to by priestesses named the Vestal Virgins, whose two main jobs, on top of praising their Goddess Vesta, was to keep the fire ignited and protect their virginity (“Vestal Virgins”).

The symbolism of fire in the history of Vesta and her priestesses is interesting to consider in the context of Portia’s Julius Caesar because in the play, fire is used to destroy Portia’s home and domestic life, and by the end of the play, Portia, her baby, and any hope of the future of her family with Brutus is razed by fire.

Vulcan, on the other hand, is described as a vengeful, ugly god of blacksmithing who is synonymous with wild, destructive fires (“Vulcan”). Romans would participate in a ceremony for this god called Vulcanalia in which they would sacrifice animals, mainly fish, as an offer to prevent wildfires from occurring (Wigington).

Given the prominence of these two gods in ancient Roman culture, the violent, transformative force of fire takes on additional meaning in Portia’s Julius Caesar. The citizens’ response to Caesar’s death can be seen as an expression of Vulcan’s vengeful use of fire, including all of this fire’s ugly and destructive associations, specifically the destruction of Portia’s home and the murder of Portia’s baby. Moreover, by the end of the play, Portia lacks the domestic life or peacefulness that Vesta’s fire represents, rather she endures the same fate of a Vestal Virgin who has committed the worst crime: losing her virginity (“The Roman Empire”).

References

Anderson, David, et al. “5 Everyday Hand Gestures That Can Get You in Serious Trouble Outside the US.” Business Insider, 5 Feb. 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/hand-gestures-offensive-different-countries-2018-6#the-v-sign-represents-peace--1.

Forbes, Sophie. “18 Gestures That Can Cause Offense around the World.” ShermansTravel, 4 Feb. 2020, https://www.shermanstravel.com/advice/18-gestures-that-can-cause-offense-around-the-world.

Geller, et al. “Vesta - Roman Virgin Goddess of Home and Family.” Mythology.net, 3 Nov. 2016, https://mythology.net/roman/roman-gods/vesta/.

“The Roman Empire: In the First Century. The Roman Empire. Worship.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/worship.html.

“Vestal Virgins.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 23 Jan. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Vestal-Virgins.

“Vulcan: The God of Fire and the Forge.” Timeless Myths, 21 Mar. 2022, https://www.timelessmyths.com/gods/roman/vulcan/.

Wigington, Patti. “Celebrating the Roman Vulcanalia Festival.” Learn Religions, 18 Mar. 2019, https://www.learnreligions.com/the-roman-vulcanalia-festival-2561471.

The Falling Sickness –

How the Romans Fell to Illness

by Connor McKechnie

“’Tis of the like, He hath the falling sickness” (Riordan). You may be thinking, “Okay…, but what is the falling sickness? And how did people feel about such a sickness in ancient Rome? And what did people of this time know about sickness, falling or otherwise?” Well, quest no further, you have found the answers.

Health

Within the Roman Republic, there was a clear appreciation for the need to maintain good health. Other than the basic human desire for the feeling of well-being, there were constant wars being waged against other nations meaning there was a requirement that a majority of men were keeping themselves in good, fit-for-fighting shape in order to play their role in maintaining a dominant military force. On top of this, the Roman Republic placed a high value on sport, including the celebration of their athletes and sporting festivals, and this brought about a popular devotion to the upkeep of physical fitness (Cushing). Taken together, these factors contributed to a Roman mindset that reinforced various regimes of resistance to illness and disease, as Roman men were encouraged to keep in good shape.

Public Outlook

With such healthy people dominating society, the common folk often looked to illness as a portent from the gods, and this encouraged them to scorn the sick, and take measures to segregate the sick from society, as they must have done something to anger the gods (Smith). This outlook continued for centuries in Europe, even to 1599, when Shakespeare was writing Julius Caesar. There is no evidence of Caesar ever experiencing a bout of “the falling sickness” at the Lupercalia, but by implementing this illness (more commonly today known as epilepsy) at this point in the story, it seems as though we are being directed towards the falling sickness as one of the many portentous things that foreshadow Caesar’s downfall in the play. Indeed, Casca illustrates this popular Roman outlook on illness in the way she registers her disgust with the unhealthy atmosphere of the Lupercalia, when she says, “durst not laugh for fear of opening my lips and receiving the bad air” (Riordan).

Medicine

Leading up to this time, the concept of what we think of today as ‘medicine’ had been a bit shaky. Alexandria, in Greece, had become a sort of capital of medical knowledge by 300 BCE, and over time, citizens of Greece realized they could leave for Rome and claim medical knowledge for sale. Of course, there were true physicians trying to help the world, but these practitioners were greatly outnumbered by charlatans and drug-dealers (Scott). There were also priest-physicians who took up residence at local shrines or temples to gods of healing or sanitation (e.g.: Aesculapius), as well as true Greek physicians who began to utilize the scientific method in their practice, utilizing experimentation and data to determine facts, rather than just making assumptions. As time went on these physicians became more organized, and more respected within society; so much so, that Julius Caesar saw their value and granted them Roman citizenry, and despite expelling all foreigners from Rome, he made an exception for teachers and doctors, as he saw the value they could bring to his army. Caesar’s protection further organized physicians within Rome, and gave them the opportunity to spend the next few hundred years establishing an official presence, including specialized schools of medicine by 225-235 A.D. (Scott).

In conclusion, to return to the diagnosis of “falling sickness,” in the time of Julius Caesar, this would mean that your life was going to be harder, and this prognosis would likely come with a prescription for wine and sitting down. While this might sound nice, such a prescription is obviously not going to solve any real problems, but it is far better than being under the care of someone who was trying to steal from you, and such was the state of most medicine in 44 BCE (Scott).

References

Smith, C. A. "The Dramatic Import of the Falling Sickness in Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar"."Poet Lore, vol. 6, 1894, pp. 469. ProQuest, http://search.proquest.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/magazines/dramatic-import-falling-sickness-shakespeares/docview/1296829128/se-2.

Cushing, Angela. “Illness and Health in the Ancient World.”Collegian, vol. 5, no. 3, Jan. 1998, pp. 44–44, doi:10.1016/S1322-7696(08)60304-2. Scholars Portal Journals

Scott, William A. “The Practice of Medicine in Ancient Rome.”Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal, vol. 2, no. 3, 1955, pp. 281–90, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03016172.

Riordan, Kaitlyn, et al.Portia's Julius Caesar. Playwrights Guild of Canada, 2018.

Roman Political Structure: Republic vs Empire

by Jaime Borromeo

What was the Political Structure of Ancient Rome?

Rome was a republican state that emerged from the overthrow of King Lucius Tarquinus Superbus (aka. Tarquin the Proud) in 509 BCE and lasted until a civil war brought about the Roman Empire in 27 BCE. Before his rule, Julius Caesar was a part of “The First Triumvirate”, which was an alliance between three prominent politicians during the Roman Republic. This alliance consisted of Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus, and their goal was to control the senate, which was rapidly declining in power as people started to have more faith in generals rather than the senators to govern the Republic. However, in 53 BCE, Crassus died in battle, which ended the alliance and started the friction between Pompey and Caesar. This led to the Roman civil war from 49 BCE to 45 BCE. In 49 BCE, Caesar left Rome for Hispania in the spring of 49 BCE “to secure the province and defeat Pompey's seven legions that were under the command of Marcus Petreius, Lucius Afranius and Marcus Varro” (“Caesar in Spain”). This was the Campaign of Ilerda and Caesar’s first act of war.

Following the campaign, Caesar was then appointed as dictator back in Rome, since Marcus Lepidus nominated Caesar and the Senate swiftly agreed. In 48 BCE, the Battle of Pharsalus took place. This was the deciding battle for the Roman civil war, where Pompey and Caesar would go head-to-head, and Caesar would come out victorious. After his loss, Pompey fled to Egypt where he was killed. Caesar was once again appointed as dictator “for an indefinite period of time” (Julius Caesar as dictator and Ides of March 44 BC). Once the war was over, he was then given the title of lifetime dictator. He had a Senate that consisted of 600-900 senators, but in decisions made by the Senate, Caesar always had the final word.

All in all, Caesar was an incredibly accomplished man. He had three goals regarding the reshaping of Rome’s “constitutional framework” which were “suppress the resistance occurring in the provinces, unite the Republic into a single unit, and establish a strong central government” (What were some of Caesar’s reforms?). He was passionate about these goals but was assassinated before they could be realized. Although he was not able to achieve those goals himself, he was still able to achieve many great feats. For example, he was one of the greatest military commanders ever. He was awarded the Civic Crown, which is the “2nd highest military decoration for a citizen” within the Roman Republic, and he “invaded Britain twice and installed a king there who was friendly to Rome (Anirudh). Another great accomplishment he achieved was reforming the calendar. He replaced the old inaccurate Roman calendar with one based on the Egyptian calendar, which was regulated by the sun. He set “the length of the year to 365.25 days by adding an intercalary day at the end of February every fourth year” (Anirudh). And those are only a couple of his many accomplishments.

To find out more about Caesar’s rule, his accomplishments, and the political structure of Rome, here are some links below:

https://www.ushistory.org/civ/6b.asp

https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome/The-dictatorship-and-assassination-of-Caesar

https://learnodo-newtonic.com/julius-caesar-accomplishments

Roman Republic

Before Julius Caesar was in absolute control of Rome, the Republic was ruled by two consuls that were elected by the people. This was the Roman Republic. Consuls were representatives who were elected by the people to serve for one year at a time. When Consuls were in charge of Rome, they had authority to govern Rome and had to agree with each other on every single decision that was made. After their time of service, they were immediately replaced and had to wait ten years to be elected again.

In addition to the Senate, the governing structure of the Roman Republic also included Magistrates and Tribunes. Magistrates were voted for by the citizens and were responsible for keeping law and order in Rome and for financial affairs. Once they retired, they became part of the Senate. The Tribunes, just like the Consuls and Magistrates, were elected by the people. They simply had to be sure that the people of Rome were treated well and with fairness. The Senate was where issues of governance were discussed, and problems solved. Senators were also responsible for giving advice to the Consuls, since they knew so much about the governance of Rome. In the early years of the Republic, they were strictly advisors for the consuls. However, as many years passed, the Senate acquired more effective control through the observance of certain unwritten rules regulating the relation between Senate and magistrates, to whom it formally gave advice. The Senate became the chief governing body in Rome and tendered advice on home and foreign policy, on legislation, and on financial and religious questions. It acquired the right to assign duties to the magistrates, to determine the two provinces to be entrusted to the consuls, to prolong a magistrate’s period of office, and to appoint senatorial commissions to help magistrates to organize conquered territory” (Senate). When Rome became an Empire, the Senators were still responsible for giving advice to the emperor.

The populace of the Roman Republic was split into different classes: patricians (the wealthy men), plebeians (working male citizens) women, and slaves (who had no money, rights or freedom).

If you want to learn more about the Roman Republic, below are some links with more information:

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/roman-republic

https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Republic

Roman Empire

There was a major period filled with unrest and civil war which marked the transition and change of Rome from a Republic to an Empire. Julius Caesar took full advantage of it, by becoming one of Rome’s Dictators. Dictatorship did exist in the Roman Republic. There was a limited time for this job, which was strictly six months. And when Caesar came to power, he demanded to be “Dictator for life”. This completely contradicted the fundamentals of the Roman Republic and was too similar to the status of a king. This caused the eventual assassination of Caesar. This event was essentially the birth of the Empire that was to exist for years after Caesar’s death. The Roman Empire was established around 27 BCE, right after the downfall of the Roman Republic, and lasted until 476 AD.

Following Caesar’s death “the triumvirate of Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian (Caesar’s nephew and heir) ruled. It was not long before Octavian went to war against Antony in northern Africa” (Roman Empire). Shortly after, Octavian was named the first Emperor of Rome, also known as Augustus Caesar. Who was the first, and longest reigning Emperor of Rome with a total of 41 years in this role. Historical accounts state that he was one of, if not the best, emperors of Rome, and this is likely because of the longevity of his reign, and that he was Emperor in an “era of relative peace that was known as Pax Romana or the Roman Peace” (Adhikari). Moreover, Augustus Caesar’s “autocratic regime is known as the principate because he was the princeps; that is, the first citizen, at the head of an array of outwardly revived republican institutions that alone made his autocracy palatable” (Grant). With “unlimited patience, skill, and efficiency, Augustus Caesar overhauled every aspect of Roman life and brought durable peace and prosperity to the Greco-Roman world” (Grant). He was “a man of the people, drawing on some Republican ideals, within the political structure of an empire wherein the citizens loved him, since it seemed he was restoring the republic” (Grant).

When it comes to the differences between the Roman Empire and the Roman Republic, the main ones are that “the former was a democratic society and the latter was run by only one man. Also, the Roman Republic was in an almost constant state of war, whereas the Roman Empire's first 200 years were relatively peaceful” (Grant). The Republic did not give the citizens an adequate voice in the early years of Rome, but as time passed the commoners, or plebeians, got upset and created their own corporation known as the Plebeian Council. This upset the Senate, but after a Plebeian dictator was elected, Quintus Hortensius, “He instituted a law (Lex Hortensia) making plebiscita (measures passed in the plebeian assembly) binding not only on plebeians but also on the rest of the community” (Plebeian). This gave the citizens of Rome a voice, but once the Empire rose to power, they were just referred to as commoners again.

As stated previously, the Roman Empire was not a democracy, there was only one man in power who had all the control. However, there was peace for a long time, as opposed to the war-ridden republican era of Rome. But within the Empire, the Senate still existed and functioned; the emperor however, had control of the government. Some emperors were glorified, such as Augustus, who was mentioned above. But some were not so great like the first successor, Tiberius. According to some sources he was an able leader; however, his short reign was “filled with reckless spending, callous murders, and humiliation of the Senate.” (Roman Empire).

For information about the Ancient Roman Empire, here are some links:

https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Empire/Height-and-decline-of-imperial-Rome

https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/julius_caesar.html

https://www.historyonthenet.com/romans-the-rise-and-fall-of-roman-empire

References

Anirudh, et al. “Anirudh.” Learnodo Newtonic, 20 Feb. 2023, https://learnodo-newtonic.com/julius-caesar-accomplishments.

“Roman Empire.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Empire.

“Roman Republic.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.,

https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Republic.

“Height and Decline of Imperial Rome.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica,

Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Empire/Height-and-decline-of-imperial-Rome.

“The Roman Empire: In the First Century. The Roman Empire. Emperors. Julius Caeser.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/julius_caesar.html.

“History.” Enotes.com, Enotes.com, https://www.enotes.com/homework-help/what-some-caesars-reforms-779736#.

“Senate.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/Senate-Roman-history.

“The Dictatorship and Assassination of Caesar.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome/The-dictatorship-and-assassination-of-Caesar.

“The Romans - Roman Government.” History, 12 Dec. 2022, https://www.historyonthenet.com/the-romans-roman-government.

“The Romans: The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire.” History, 12 Dec. 2022, https://www.historyonthenet.com/romans-the-rise-and-fall-of-roman-empire.

Findley, Kate. “Unpacking the Titles of Augustus: Wordplay and Double Meanings.” Wondrium Daily, 6 Jan. 2020, https://www.wondriumdaily.com/unpacking-the-titles-of-augustus-wordplay-and-double-meanings/.

S, Alen, et al. “Julius Caesar as Dictator and Ides of March 44 BC.” Short History Website, 18 Sept. 2016, https://www.shorthistory.org/ancient-civilizations/ancient-rome/julius-caesar-as-dictator-and-the-ides-of-march-44-bc/.

The Do’s and the Don’ts of Married Life

by Connor McKechnie

It is said that Portia and Brutus’s marriage was unique, a modern bond to which Romans might aspire, and as such an abnormality of the time. If that is true, then what was the norm of this time? What was expected of a husband, or a wife? And what were the lines of morality that were drawn around them by the societal norms of the Roman Republic?

The Public Ideal of a Roman Family

The Roman family was of the utmost importance and was ruled, according to law, by the Paterfamilias, or the senior-most male member of the family. The influence of the Paterfamilias extended so far that when a child was born, he could choose to accept or reject the child, and if rejected, this newborn would essentially be abandoned in the street, where they were likely to be adopted by slaves (PBS). While the Paterfamilias and men held the power publicly, the Materfamilias and the women, were expected to be the ones running the household, and often did what they could to exert their influence in private (PBS). Marriage was significant in creating a family in Ancient Rome, as a man’s child could only be recognized as legitimate if conceived by his spouse (Treggiari). Marriage was an important step in securing one’s legacy.

Within the Roman, male-dominated culture, it was understood that legally a man could order his wife to do things, but the reality may not have been so stark. A joke, attributed to Cato, suggests a more complicated relationship between a husband and wife: “All men rule their wives, we rule all men, our wives rule us” (Treggiari). This possible lack of control, combined with the need of a wife, drove many men to loathe their marriage, and think of their wives as a curse, or a burden, and seek out many wives throughout their lifetime (Treggiari). And while monogamy was an ideal for women, they were still encouraged to remarry when widowed or divorced, unless perhaps, they were beyond childbearing age (Treggiari). All this is not to suggest that love was not present in Roman marriages; indeed, it was an explicit expectation of the contract, and consent was a requirement for the marriage to take place, but this did not prevent politically-motivated, loveless, marriages. Moreover, the presence of divorce meant that a good many Roman marriages did not last (Treggiari).

The children of Roman families were raised primarily by wet-nurses and the mother, but the father was expected to oversee the moral education of male children from ages 15-25/30, while male children without fathers would often end up being taught by uncles, step-fathers, and friends of the family (Rawson). This didn’t stop many fathers from developing close bonds with their daughters, while mothers often formed very close bonds with their sons. The bond between mother and son could usually be an expected point of contention for new wives, and they would have to work hard to prove to their mother-in-law that they could provide for their son’s needs (Treggiari).

Sexual Relations

Adultery, as we know it in a legal sense, did not come about until the Silver Age (about 50-100 years after the life of the Julius Caesar focused on in Portia’s Julius Caesar) and could even become grounds for capital punishment (Treggiari). The definition of what adultery was, and who was considered an adulterer, is something that came about before any laws were put into place, and Traggiari’s observations about the word are quite interesting:

Papinian points out that the Julian Law on adultery used the words stuprum (illicit intercourse) and adulterium indifferently, but he says that strictly adulterium is committed with a married woman, and that the word comes from the fact that she conceives a child by a man other than her husband. Stuprum is committed with a virgin, widow, or divorcee. It is interesting that he stresses the production of an illegitimate child, not the sexual infidelity of the wife (Treggiari).

This is followed up by their conclusion that “[n]ormal usage does not define an adulter as a married man who has paelex (mistress)” (Treggiari). Therefore, in the Roman Republic of Portia’s Julius Caesar, adultery was frowned upon if the adulterer was a wife, but there was not such a negative connotation given to husbands, so long as the woman they were with, was not married. This is illustrated further in the fact that adultery was just cause for divorce, while a man could not in fact be defined as an adulterer.

References

Treggiari, Susan. Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian. Clarendon Press, 1993.

McGinn, T. A. J. Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome. Rawson, Beryl, Ed.: New York: Oxford University Press, 252 Pp., Publication Date: August 1991.History (Washington), vol. 21, no. 3, 1993, pp. 133–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/03612759.1993.9948701.

“The Roman Empire: In the First Century. The Roman Empire. Life in Roman Times. Family Life.”PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/family.html.

Rome’s Fragmented History: The Legend of Romulus and Remus

by Kat Sill

Rome has a long and fragmented history linked to numerous stories, archeological findings, myths, and legends. For that reason, the year of Rome’s founding is the subject of debate; while April 21st is the day most agree to be Rome’s birthday, and as such, the ancient Roman festival, Parilia, was celebrated on this day (Britannica, 2019). Marcus Terentius Varro, a polymath considered to be one of Rome’s greatest scholars, is credited with setting the date of Rome’s founding on April 21st,753 BCE (HISTORY.com Editors). However, in the fourth century BCE, the legend of Romulus and Remus originated and became a popular part of Rome’s tradition (Britannica, 2022).

According to legend, Romulus and his twin brother Remus were the sons of Rhea Silvia, the daughter of Numitor, a king of Alba Longa. She was forced to become a Vestal Virgin before the birth of her sons when her Uncle Amulius, usurped her father’s crown, became king, and killed Rhea’s brothers removing all heirs. The father of Romulus and Remus is debated to be either Mars, the God of War, Hercules, a demi-god, or an unknown man, who raped Rhea Silvia (Garcia). As Vestal Virgins took oaths of celibacy, the consequence for breaking such oaths was death. However, King Amulius did not want to be directly involved in killing Rhea Silvia and the children potentially connected to a god, and so he imprisoned Rhea Silvia and ordered the death of the twins by the earth’s elements: buried alive, exposure, or drowning in the Tiber River. The servant ordered to exercise this sentence took pity on the twins and instead of throwing them into the Tiber River, placed them in a trough and sent them down the river to safety.

"Tiberinus, the God of the Tiber River, ensured the boys safety by controlling the current so that their basket snagged on the roots of a fig tree, located at the bottom of Palatine Hill” (Garcia). It is from here that a she-wolf suckled them and a woodpecker fed them until the shepherd, Faustulus, found them and decided to raise them with his wife, Acca Larentia (Garcia). Years later, when the twins were shepherding, they came across shepherds who served King Amulius. These shepherds discovered the identity of the twins, and in the altercation that followed, Remus was captured. However, when put before King Amulius, who believed the boys to be dead, neither he nor Romulus was recognized, which allowed for the group that Romulus had rallied together, to free his brother and kill King Amulius.

While the citizens of Alba Longa offered the twins the crown, they reinstated Numitor as King and left the city in search of a new home. While Romulus believed the best location was Palatine Hill, Remus preferred Aventine Hill, and thus, to settle the debate between the two, they turned to augury: the examination of birds deemed prophecy of a god’s favour (Garcia). Both brothers believed they saw different favourable premonitions, and they remained at odds until Romulus began to dig trenches around Palatine Hill and build walls on the edge of these trenches, which became a constant source of mockery from Remus. While it is debated whether Remus in jest jumped over the wall and unintentionally killed himself, as described by Livy, or died due to one of Romulus’ supporter’s throwing a spade at his head as alleged by St. Jerome, or the more popular retelling that Romulus killed his brother in anger, Remus died, and Rome, named after Romulus himself, was founded on April 21st, 753 BCE (Garcia).

References

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Parilia".Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Nov. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parilia.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Romulus and Remus".Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Dec. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Romulus-and-Remus.

Garcia, Brittany. "Romulus and Remus."World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 18 April 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/Romulus_and_Remus/

HISTORY.com Editors. “Rome founded.” HISTORY. A&E Television Networks, 19 April 2022. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/rome-founded

Hooper, John. “Archaeologists’ findings may prove Rome a century older than thought.” The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited, 13 April 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/13/archaelogists-find-rome-century-older-than-thought

National Geographic Society. “The gods and Goddesses of Ancient Rome.” National Geographic Society. 12 October 2022. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/gods-and-goddesses-ancient-rome

Roux, Marie. “Livy, History of Rome, Preface 6-9.” 24 July 2017. Judaism and Rome. https://www.judaism-and-rome.org/livy-history-rome-preface%C2%A06-9

Roman Society and Slavery in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and Kaitlyn Riordan’s Portia’s Julius Caesar

by Miranda Chen

Slavery is one of the distinguishing traits of ancient Roman civilization, which is portrayed in Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar as a complicated and hierarchical institution. Through the play's characters and actions, the topic of slavery and Roman society's social structure are portrayed. The drama offers a distinctive look into the social, political, and economic realities of ancient Rome and how these realities affected the lives of its residents, especially slaves. Also, it captures the realities of a highly stratified society in which slaves were at the bottom of the social strata and treated more like property than people. It is implied that the slaves are at the mercy of their masters and frequently endure terrible and degrading treatment. In this article, I hope to illuminate the role of slavery in ancient Roman society as it is depicted in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and how this socio-political context has informed Kaitlyn Riordan’s adaption of Shakespeare’s play, in Portia’s Julius Caesar.

In Julius Caesar, the institution of slavery is depicted as a common and accepted practice in Roman society. In the play, the characters of Flavius and Marullus, who are tribunes of the people, express their disgust at the commoners (i.e.: the slaves) for rejoicing at Caesar's triumphal procession, instead of mourning the loss of their freedom. This highlights the fact that even in a society where slavery was prevalent, there were some who recognized its negative effects and spoke out against it. The character of Pindarus, a slave, serves as a symbol of the complete control and power that owners had over their slaves. He is ordered to kill his master Cassius by Cassius himself, illustrating the ruthless nature of Roman society toward slaves. This also reflects the idea that slaves were considered property, at the mercy of their master’s command, rather than individuals with rights and freedoms.

The play also reflects the complex social and political dynamics of ancient Rome. The ruling class, represented by the senators, is depicted as being divided and self-interested, with the commoners having little say in the political affairs of the state. There is a huge difference between commoners and slaves. Commoners, or free citizens, were individuals who were born or granted citizenship in the Roman Republic. They enjoyed certain rights and privileges such as the right to own property, participate in government, and engage in commerce. Although social and economic status varied greatly among commoners, they generally had greater freedom and autonomy than slaves. On the other hand, slaves were individuals who were considered property and had no legal rights. They were owned by their masters, who had complete control over their lives, including the power to buy, sell, or even kill them. Slaves were often forced to work long hours in harsh conditions without pay, and they could be punished severely for disobedience or attempting to escape. Although there were some legal protections for slaves, such as prohibitions against certain forms of physical abuse, they were still considered property and did not have the same rights and freedoms as free citizens.

The conflict between Caesar, who is depicted as a powerful and ambitious leader, and the senators, who fear his increasing power, highlights the tension between the ruling class and the rest of society, including the slaves. This conflict also reflects the struggle for power and control that was prevalent in ancient Rome, with different groups vying for influence and control over the state. In Portia’s Julius Caesar, this central conflict is essentially the same; however, Riordan reflects this conflict more from the perspective of female characters, such as Servilia, Calpurnia, and Portia.

In addition to political tensions, Julius Caesar and Portia’s Julius Caesar also reflect the cultural and moral values of Roman society. For example, the character of Brutus, a senator, is depicted as being torn between his loyalty to Caesar and his love for his country. In both plays, he ultimately chooses to betray Caesar and join the conspirators in their plot to kill him, claiming that he is doing so for the good of the state. This highlights the importance of patriotism and loyalty in Roman society and the moral dilemmas that individuals faced in their quest for power and control.

Furthermore, both plays reflect the idea of the "noble Roman," which was a cultural ideal that emphasized virtue, or moral strength, and bravery. This ideal is embodied in the character of Brutus, who is depicted as being an honorable and virtuous man, despite his involvement in Caesar's assassination. This portrayal reflects the complex and conflicting values that existed in ancient Rome, where individuals were expected to balance their loyalty to their leaders and their love for their country with their own personal interests and desires.

In conclusion, both Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and Kaitlyn Riordan’s Portia’s Julius Caesar reflect the complex and hierarchical nature of ancient Roman society, including the institution of slavery and the power dynamics between different social classes. Both plays provide a vivid picture of the political, social, and cultural realities of Rome, circa 44 B.C., and as such serve as valuable resources for our understanding of the complexities of ancient Roman society. Through characters and events, both plays shed light on the moral, ethical, and political issues that the people of ancient Rome faced, providing insights into the human condition that are still relevant today. The difference is found in how Riordan develops the female characters in Shakespeare’s story, and in so doing offers a unique perspective on how the themes of power, ambition, and loyalty – which are central to both plays – are enacted; such an adaptation ensures that this story of ancient Roman society will continue to resonate with audiences today, and provide a thought-provoking commentary on the nature of power and politics.

References

“Ancient Rome.” Ducksters, https://www.ducksters.com/history/ancient_rome/slaves.php.

Cartwright, Mark. “Slavery in the Roman World.” World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org#Organization, 3 Feb. 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/629/slavery-in-the-roman-world/.

Harper, Kyle, and Walter Scheidel. “Roman Slavery and the Idea of ‘Slave Society’ (Chapter 3) - What Is a Slave Society?” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/what-is-a-slave-society/roman-slavery-and-the-idea-of-slave-society/D48723F99A7A213625E03954CAAB7D47.

HistoryExtra. “Slavery in Ancient Rome: How Important Were Enslaved People to Roman Society?” HistoryExtra, HistoryExtra, 30 Aug. 2022, https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/slavery-ancient-rome-life-society-jobs-freedom/.

Joshel, contributed by: Sandra. “Roman Slavery and the Question of Race, 15 Oct. 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/perspectives-global-african-history/roman-slavery-and-question-race/.

“The Roman Empire: In the First Century. The Roman Empire. Social Order. Slaves & Freemen.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/slaves_freemen.html.

“Slavery in Ancient Rome.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/exhibitions/nero-man-behind-myth/slavery-ancient-rome#:~:text=Under%20Roman%20law%2C%20enslaved%20people,from%20texts%20written%20by%20masters.

Cleopatra’s Julius Caesar

by Wanda Kidd

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (Cleopatra: “Famous in Her Father”; Thea Philopator:

“the Father-Loving Goddess”)

The Ptolemy dynasty lasted from 323 BCE, founded by Alexander the Great’s general, and ended in 30 BCE when Egypt was annexed by Rome. The Ptolemy line had very little, if any, Egyptian blood; they maintained their Macedonian ancestral line by marrying close relatives. Cleopatra herself was likely married to her brother, Ptolemy XIII. After their father passed away, when Cleopatra was eighteen, and Ptolemy XIII was ten, they assumed joint rule, but civil war soon broke out as each struggled for control. Cleopatra left Egypt and raised an army in Syria.

At the same time, Pompey had sought refuge from Ptolemy XIII, but instead of granting him protection, Ptolemy’s court had Pompey assassinated, perhaps to garner favour from Caesar who was closely pursuing him. When Caesar arrived, he attempted to facilitate peace between the siblings, but Ptolemy’s forces prevented Cleopatra’s return to Alexandria. In a theatrical and now immortally famous story, Cleopatra had herself smuggled into the palace at Alexandria in a carpet delivered to Caesar. She needed Caesar’s aid to regain her throne, and Caesar needed Egypt to repay the debts from her father’s own civil war, and so their alliance began with a winter besieged in Alexandria.

Roman forces eventually arrived and ended the seige; Ptolemy XIII drowned in the Nile, and Cleopatra ascended to the throne, now married to Ptolemy XIV, also her brother. In June 47 BCE Cleopatra gave birth to Ptolemy Caesar, giving Caesar additional reasons to support Cleopatra’s fight for the throne. After the Pompeian opposition was fully stamped out two years later, Caesar returned to Rome and celebrated his triumph in 46 BCE. Cleopatra visited Rome with her brother-husband and son, hosted by Caesar in his own private villa, and was in Rome when Caesar was murdered in 44 BCE. Her brother-husband died soon after; Cleopatra herself may have had him killed, as a competitor for the throne, now that her ally Caesar was dead, and her sister Arsinoe died soon thereafter, likely for the same reason.

Enter Marcus Antonius

After Marcus Antonius had defeated Caesar’s murderers, he became the clear choice to succeed Caesar in power. Octavian, Caesar’s blood heir, was a boy and quite unhealthy. Antonius sent for Cleopatra, who arrived on a boat loaded with gifts and in the robes of the new Isis, of whom she claimed to be the living embodiment. Antonius styled himself as the new Dionysus, and Cleopatra’s theatrical entrance captivated him, although he was already married. He returned to Alexandria with Cleopatria, and in 40 BCE she gave birth to twins. Antonius had married Octavian’s sister, his previous wife having died, in an attempt to settle his struggle with Octavian for power over the Roman Republic. Eventually he was convinced they would never settle their conflict, and abandoned his wife for Cleopatra. She could give him the funds necessary for his campaign, and Cleopatra in exchange wanted large portions of Egypt’s empire returned to her including Syria, Lebanon, and Jericho.

Antonius failed in his war campaign, but upon returning to Alexandria proclaimed Ptolemy Caesar to be Caesar’s only son. Octavian responded by stealing Antonius’ will (or claiming to) and revealing to the citizens of Rome that he had left much to Cleopatra, a foreign woman, and that he intended to be buried with her.

Octavian convinced the Senate to declare war on Egypt in 32 BCE, to finally end the contests against his right to rule. In battle against Octavian’s forces, Antonius mistakenly believed Cleopatra had already committed suicide and fell on his sword. Cleopatra died by suicide a few days later. Caesarion was murdered, but the twins were spared.

With all competitors for the throne dead, and with them the Roman Republic, Octavian rose to power and assumed the name Augustus. Thus began Imperial Rome.

References

Holland, Barbara. "Cleopatra: What Kind of a Woman was She, Anyway?" Smithsonian, vol. 27, no. 11, 02, 1997, pp. 56-64. ProQuest, http://search.proquest.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/magazines/cleopatra-what-kind-woman-was-she-anyway/docview/236894537/se-2.

Tyldesley, Joyce. "Cleopatra". Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Nov. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cleopatra-queen-of-Egypt. Accessed 2 March 2023.

TO LIVE AND SERVE IN ANCIENT ROME - HOW IS IT DECIDED?

by Colleen Macaulay

A common theme we see throughout Portia’s Julius Caesar is the reality of a world with a strict division of power; from Servilia’s control over the bodies of her slaves to Caesar’s desire to be king, despite opposition from others. But how does this system really work? What deems a person higher or lower in class? Freeborn Romans were separated by categories based on ancestry, gender and citizenship. Those born to parents in power were called patricians, these families made up most of the senate, and they owned the best or most of the land. Those born to the ‘common people’ or lower class were deemed plebeians (Peachin). This system of hierarchical order also allowed for a patronage society; that is, those with more power would enlist the materials and labour from those with less power in exchange for money or land. With this, there is another category of distinction that divides Romans, and that is gender. Men were the head of the household in ancient Rome, and their wives, sisters, and mothers could not vote or hold political office because they were under the control of their fathers or husbands. In fact, “Roman women's history inevitably gets told as a series of stories about famous individuals who emerge onto the stage of history, at least in part, because they are related to socially or politicallyprominent men” (Milnor). This is similar to Portia’s Julius Caesar, wherein both Calpurnia and Portia are only captured in history thanks to the man to whom they are married. In Calpurnia's case, her history only begins to be recorded after she marries Julius Caesar, and most of the facts on her life pre-marriage is about her father and his identity.

Women in Rome, circa 44 B.C., were seen as the representation of the home and domestic life, taking care of the home and bearing and caring for children (Milnor). The last category that citizens in Rome would have fallen into was based on their citizenship. Many people did not qualify to be a citizen at the time of Portia’s Julius Caesar; prostitutes, like the character of Casca, were not considered to be Roman citizens. Despite providing a great deal to the economy, this means that prostitutes could not vote, nor work, in certain jobs. With Rome, circa 44 B.C., being a slave-keeping society, slaves made up a considerable sector of this world with no citizenship nor basic human-rights. Masters were able to deploy their slave(s) into any job no matter how demanding, except any military service (Schumacher). They were also forbidden from getting legally married and any cohabitation was at the discretion of their masters; however, such arrangements were not legally binding or relevant (Schumacher). Slaves were without any self-determination; they were property and meant to be sold and bought. Even so, their gender still mattered, women often laboured on “spinning wheels and on looms, while male slaves toiled in fulleries and felting shops” (Schumacher).

All in all, Ancient Rome separated its people by what they owned and their gender, if you were born lower on the hierarchy, you remained there and vice versa. One non-legally binding classification that was also followed by Romans was their honour value. Romans who caused insult to their family or another Roman were at risk of being killed for their offenses (Lendon). Higher ranked Romans held themselves to certain levels of honour, “the hot-blooded, fragile honour of the rhetorical schools, where insult and unchastity were avenged with killing” (Lendon). Romans had a multitude of ways to distinguish where their citizens landed within the hierarchy. Unfortunately, many people were subjected to their ranks from birth and rarely, if ever, had the chance to move up.

References

Lendon, J. E., ' Roman Honor', in Michael Peachin (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World (2011; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Sept. 2012), https://doi-org.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195188004.013.0018, accessed 2 Feb. 2023.

Milnor, Kristina, ' Women in Roman Society', in Michael Peachin (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World (2011; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Sept. 2012), https://doiorg.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195188004.013.0029, accessed 2 Feb. 2023.

Peachin, Michael. The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Schumacher, Leonhard, ' Slaves in Roman Society', in Michael Peachin (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World (2011; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Sept. 2012),https://doiorg.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195188004.013.0028, accessed 2 Feb. 2023.

The Price of Fertility

by Colleen Macaulay

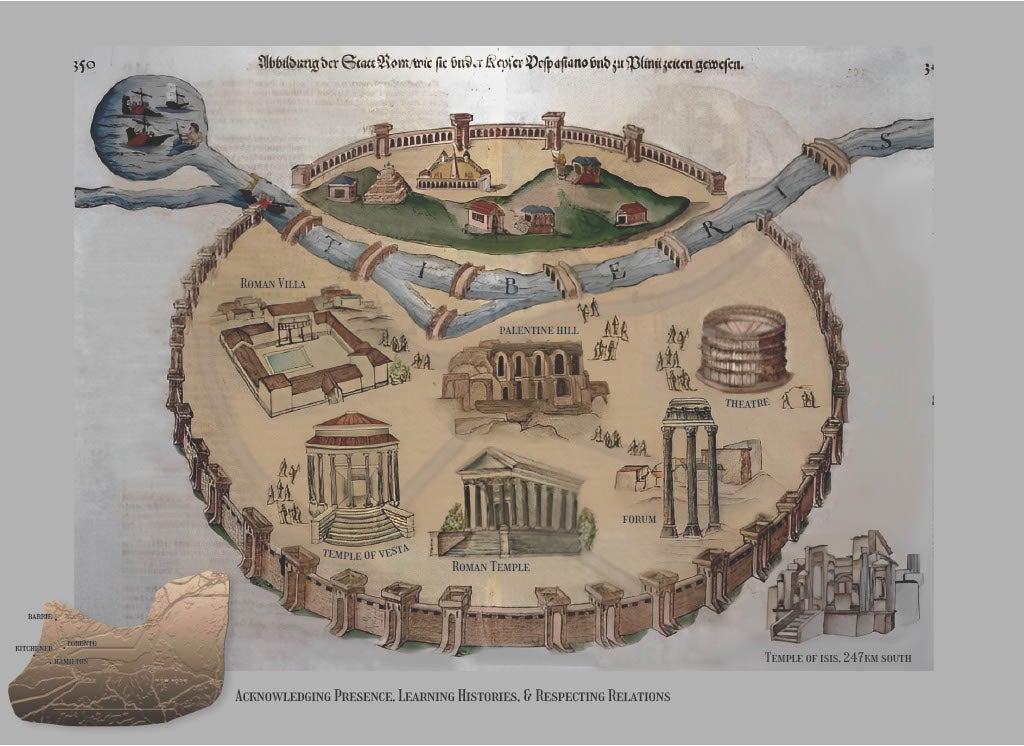

In Portia’s Julius Caesar, the Goddess Isis and the Temple of Isis are seen to be significant to Calpurnia. In the second scene of the play, Calpurnia travels to the temple to make offerings to the Goddess Isis in exchange for a baby/her fertility. Indeed, we learn that Calpurnia often makes the trek to the Temple, from her home Rome. This journey, done on foot, takes 51 hours, meaning Calpurnia would have traveled over 2 days to give her offerings and absorb all that the temple had to offer. This was a very common ritual enacted by women in ancient Rome.

The Goddess Isis is known as the “life giving-deity” (Pompeii Sites), and mythology tells us that when Isis’s husband Osiris, Egyptian Lord of the Underworld (Britannica), was slain by his brother, and fourteen of his body parts were scattered throughout Egypt, Isis collected them and revived him. She is said to have done so with her magical powers that she later would use to help her followers. Isis then went on to bear his child, Horus, to whom the birth house, or mammisi, within the temple is now dedicated (Lonely Planet).

The temple was also home to the Cult of Isis, which is documented to have been active until at least 550 A.D. (Lonely Planet). Records state that this cult had a lot of similarities to the Catholic Christian religion and its doctrines, with images of Isis mirroring those of Mother Mary. Furthermore, the Cult of Isis included baptisms, confessions, and asking for forgiveness of sin (Spence). It is said that those who followed Isis would be healed by her when sick and she would protect the women and children who graced her temple (Spence). Members also gave material sacrifices during yearly rituals and daily services. One event that the cult celebrated once a year, in March, was that of Navigium Isidis (the voyage of Isis) Festival. Those who celebrated would dress up as mythological characters, they would place images of Isis and sacred objects upon replicas of Isis’s holy boat and then send it off into the water. This was also accompanied by music and dancing throughout the entirety of the ceremony (Spence). It can be assumed that, along with her daily services and offerings, Calpurnia would have taken part in this festival due to her ongoing commitment and sincerity towards the Goddess Isis.

The Navigium Isidis Festival took place shortly after the Lupercalia, a festival featured in Portia’s Julius Caesar. The two festivals go hand in hand, as the women of the temple would stand in the way of the men partaking in the Lupercal to ensure they would be hit by their whips as they ran by. Doing this was said to increase the fertility of the women as it would rid their body of the curse believed to be placed upon them. It is also said that Isis connected to her followers through their dreams, this is where she would invite new followers and once this invitation was received it was not to be declined (Spence). Perhaps this is how Calpurnia began her following? The Temple of Isis is also the last known temple built in Classical Egyptian style, with construction beginning in 690 B.C. (Lonely Planet).

References

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Osiris". Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Dec. 2022,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Osiris-Egyptian-god. Accessed 4 February 2023.

“Temple of Isis.” Pompeii Sites, 19 May 2020,

https://www.pompeiisites.org/en/archaeological-site/temple-of-isis/. Accessed 5 February 2023.

“Temple of Isis: Southern Nile Valley, Egypt: Attractions.” Lonely Planet,

www.lonelyplanet.com/egypt/nile-valley/philae-agilkia-island/attractions/temple-of-isis/a/poi-sig/1050336/355252. Accessed 5 February 2023.

Spence, Richard B. “The Isis Cult-the Story of the Egyptian Goddess.” Wondrium Daily, 8 Aug.

2020, www.wondriumdaily.com/the-isis-cult-the-story-of-the-egyptian-goddess/#:~:text=Just%20like%20Christians%2C%20rituals%20of,was%20even%20a%20sacred%20meal. Accessed 5 February 2023.

Google map route: Palatine Hill, Rome to Temple of Isis: