Some thought that moderate living and the avoidance of all superfluity would preserve them from the [Black Plague]. They formed small communities, living entirely separate from everybody else. They shut themselves up in houses where there were no sick, eating the finest food and drinking the best wine very temperately, avoiding all excess, allowing no news or discussion of death or sickness, and passing the time in music and suchlike pleasures. Others thought just the opposite. They thought the sure cure for the plague was to drink and be merry, to go about singing and amusing themselves, satisfying every appetite they could, laughing and jesting at what happened. They put their worlds into practice, spent day and night going from tavern to tavern, drinking immoderately, or went into other people’s houses, doing only things which pleased them.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron

The Decameron | The Plague | References

The Decameron

Was I the only one who even read the book?

Concord Floral begins with a group of high school students fleeing their class project on Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a 14th century story written during the Italian Renaissance. As the ten teenagers in this play struggle against a plague of their own secrets hidden in Concord Floral, ten teenagers in The Decameron escape from plague-ridden Florence – a city filled with victims of the Black Death – to an ornate countryside villa.

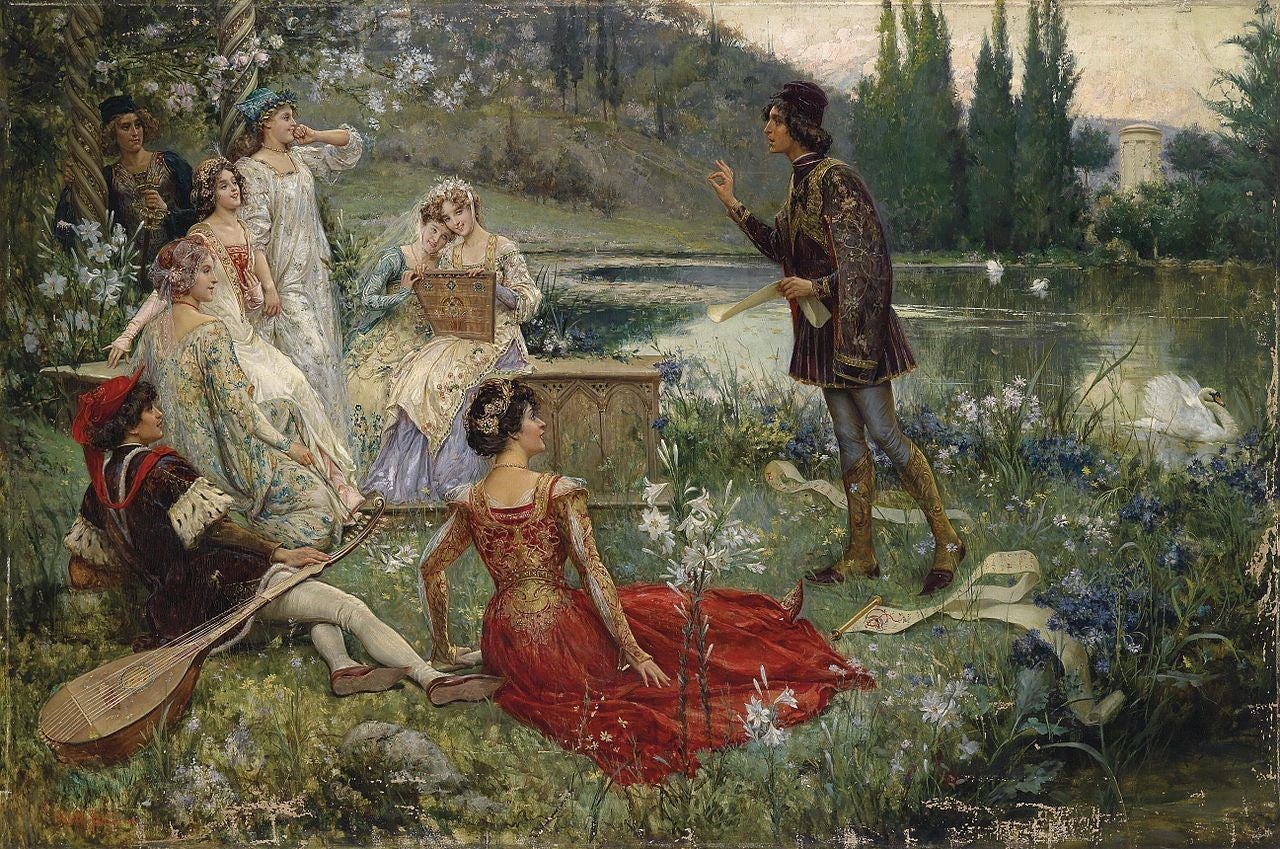

The

Decameron,

by

Franz

Xaver

Winterhalter

(1837)

The

Decameron,

by

Franz

Xaver

Winterhalter

(1837)

So they just chilled in this big abandoned greenhouse?

In the villa, they live in absolute freedom for a fortnight. Each teenager takes a turn ruling as king or queen over the other nine and has the opportunity to dictate how the days shall be spent, what will be danced and sung, and, above all, what stories will be told. As how the title of “The Decameron” translates to “Ten Days’ Work,” the teenagers devote ten days of the fortnight to telling a culmination of 100 stories. Each story ends with a canzone, or a song meant to be danced to, sung by the storyteller.

A Tale from the Decameron, by John William Waterhouse (1916)

Do you even know what the plague is?

Not only does The Decameron juxtapose the sombreness of death via sickness and contagion with the gaiety of adolescent freedom, but the stories the teenagers tell each other are themselves often oppositional. Some end in tragedy. Some end happily. Some are about love, while others centre on deception. Do these teenagers understand the enormity of what they have escaped from, or the significance of the haven they create for themselves? Do the teenagers of Concord Floral understand the gravity of the stories they create, then recreate, live, then relive? It is impossible to say. The only way to come close to the answer is to watch these stories unfolding onstage, and to therefore be part of the questions that come from the secrets they show us.

Motiv aus der Erzählung des Dekameron (Il Decamerone) von Giovanni Boccaccio, by Salvatore Postiglione (1906)

The Plague

Are you scared?

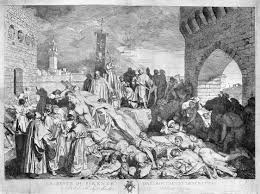

The Black Plague, or the Black Death, killed approximately fifty million Europeans between 1346-53, a greater loss than any previous epidemic or war had led to. Believed to have originated in China and Inner Asia, this epidemic of bubonic plague spread from the Genoese trading port of Kaffa to mainland Italy, Spain, France, England, and large portions of other European regions. By 1350, it had reached Scotland, Scandinavia, and the Baltic countries. This disease is commonly theorized to have been caused by a bacterium that spreads among high populations of wild rodents living in close proximity. Scholars believe that highly contagious infected black rats and rat fleas initially transmitted this illness to humans, who then transmitted it to one another.

Danse macabre, by Michael Wolgemut (1493)

Victims of this plague would often experience swollen lymph glands, fever, nausea, and severe weakness 3-5 days after first being infected. 80% would die in another 3-5 days. The disease was likely named the Black Death because victims would often develop characteristic dark patches on the skin caused by subcutaneous bleeding. Because of the Medieval Age’s lack of medical knowledge regarding how the pandemic spread, treatments included washing those infected in vinegar and rose water, fumigating living quarters with herbs, and bleeding blood thought to carry the illness from bodies. Even as reoccurrences of the Black Plague struck Europe until 1400, treatment remained largely unsuccessful.

The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio’s Decameron, by Luigi Sabatelli

The consequences of the Black Death were devastating. Due to the sudden deaths of an immense amount of farmers, many landowners suffered economic losses from a reduction of land being cultivated. Furthermore, fear of contagion caused intense psychological tension throughout much of Europe. Neighbours, paranoid about catching ill, refused to interact with one another. Citizens would spend days collecting and burying the dead in silence, with little time to mourn. Art in regions north of the Alps reflected a preoccupation with death, while much Renaissance literature, such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, was inspired by this violent catastrophe.

One citizen avoided another, hardly any neighbour troubled about others, relatives never or hardly ever visited each other. Moreover, such terror was struck into the hearts of men and women by this calamity, that brother abandoned brother, and the uncle his nephew, and the sister her brother, and very often the wife her husband. What is even worse and nearly incredible is that fathers and mothers refused to see and tend their children, as if they had not been theirs.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron

The Decameron

Bosco, Umberto. Giovanni Boccaccio. Encyclopedia Britannica. November 19, 2014, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giovanni-Boccaccio. Accessed September 16, 2017.

Salvatore Postiglione. Motiv aus der Erzählung des Dekameron (Il Decamerone) von Giovanni

Boccaccio. 1906, oil on canvas.

Waterhouse, John William. A Tale from the Decameron, 1916, oil on canvas, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

Winterhalter, Franz Xaver. The Decameron. 1837, oil on canvas, Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna.

The Plague

Adams, Leah. The Plague of Death. Back to Basics, 18 December 2010, http://www.leahadams.org/back-to-basics-the-plague-of-death/. Accessed 28 September 2017.

Black Death. Encyclopædia Britannica, 31 July 2017, https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death. Accessed 28 September 2017.

Killilea, Alfred G. and Lynch, Dylan D. Confronting Death: College Students on the Community of Mortals. iUniverse, 2013.

Sabatelli, Luigi. The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio's Decameron.

The Black Death. BBC, 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/ks3/history/middle_ages/the_black_death/revision/5/. Accessed September 2017.

The Black Death of 1348 to 1350. History Learning Site, 2016, http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/medieval-england/the-black-death-of-1348-to-1350/. Accessed 28 September 2017.

The Black Death, 1348. EyeWitness to History, 2001, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/plague.htm. Accessed 23 September 2017.

Trueman, C.N. Cures for the Black Death, 20 October 2016, http://www.historylearningsite.co. uk/medieval-england/cures-for-the-black-death/. Accessed 28 September 2017.

Wolgemut, Michael. Danse macabre. 1493.