THE ENGLISH

Henry VI was the king of England and lord of Ireland, and duke of Aquitaine at the age of nine months. He was born at Windsor Castle on the feast of St. Nicholas, the 6th of December in 1421. He was the only child of Henry V (1386-1422) and Catherine of Valois (1401-1437). Henry’s godfathers were two senior members of the house of Lancaster; his great uncle, Henry Beaufort, bishop of Winchester, and Henry V’s brother John, duke of Bedford. Henry V died at Vincennes, near Paris in 1422, never meeting his son. In accordance with the treaty of Troyes (1420), baby Henry VI succeeded to the English throne as well as claims in France.

Reading:

Craig, Leigh Ann. "Royalty, Virtue, and Adversity - the Cult of King Henry VI." Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 35:2 (Summer, 2003): 187-209.

Davies, John Silvester. An English chronicle of the reigns of Richard II., Henry IV., Henry V., and Henry VI. written before the year 1471 : with an appendix, containing the 18th and 19th years of Richard II. and the Parliament at Bury St. Edmund's, 25th Henry VI. and supplementary additions from the Cotton. ms. chronicle called "Eulogium." London: Camden Society, 1856.

Ellis, Henry (Ed.) Three books of Polydore Vergil's English history : comprising the reigns of Henry VI, Edward IV, and Richard III from an early translation, preserved among the mss. of the old royal library in the British Museum. London: Camden Society, 1844.

Goodall, John A. A. " The Lancastrian Age: Henry IV..., Henry V and Henry VI." The English Castle, 1066-1650. New Haven: Yale UP, 2010. UW Library Arch.

Griffths, Ralph. The reign of King Henry VI : the exercise of royal authority, 1422-1461. London: E. Benn, 1981. Porter Library.

Oyelowo, David. Actors on Shakespeare - Henry VI Part One. London: Faber and Faber, 2003.

Stevenson, Joseph. Letters and papers illustrative of the wars of the English in France during the reign of Henry the Sixth, King of England. Wiesbaden: Kraus Reprint 1965. UW Library Annex.

Watts, John Lovett. Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship. New York: Cambridge UP, 1996. Porter Library.

Source: Griffiths, R.A. ‘Henry VI (1421–1471)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/12953, accessed 28 April 2015]

Biography from the Official Website of the British Monarchy

John of Lancaster, duke of Bedford (1389-1435), regent of France and prince, was born in 1389, the third son of Henry Bolingbroke, afterwards Henry IV. From Henry IV’s accession, John began to accumulate lands and offices in England that laid foundations for his later wealth. He was knighted in 1399 and his first military experience was in border warfare. When Henry invaded France in 1415 for the campaign that led to Agincourt, Bedford remained in England as lieutenant. Bedford was with Henry when the treaty of Troyes or ‘final peace’ was signed, in 1420. The treaty was the basis of the ‘dual monarchy’, the Lancastrian claim to rule France as well as England. Circumstances dictated that Bedford would spend the rest of his life defending the claims of his brother and his nephew to the French crown

Source: Stratford, Jenny. ‘John, duke of Bedford (1389–1435)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/14844, accessed 28 April 2015]

Sometimes known as Good Duke Humphrey, Gloucester was a prince, soldier, and literary patron. He was the youngest son of Henry IV, protector of England during Henry VI’s minority and first English patron of Italian humanism. Gloucester served with a large contingent to Harfleur in 1415 and later fought at Agincourt, where he was wounded; his life was saved by Henry V. He had a much decorated military career. Upon Henry’s death in 1422, Gloucester was made principal tutor and protector of Henry VI in a codicil of Henry V’s will. Gloucester interpreted the codicil as governance of the kingdom as well, and he faced opposition from both Bedford and council. He resented being denied regency and while he did not initially withdraw from the council, he did see his influence diminish and his natural leadership increasingly usurped.

Reading:

Cordery, Richard. "Duke Humphrey in Parts 1 and 2 of Henry VI, and Buckingham in Richard III." Players of Shakespeare 6 [F]: 184-97.

Source: Harriss, G.L. ‘Humphrey , duke of Gloucester (1390–1447)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/14155, accessed 28 April 2015]

Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester

The second of John of Gaunt’s four illegitimate children. Having completed the arts course and commenced the study of theology he was ordained deacon on 7 April 1397. Winchester served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1403 – 1413, during which Henry IV faced the revolt of the northern lords, including Henry 'Hotspur' Percy as well as the continuing French threat to Calais. In the summer of 1415 his palace became the king’s headquarters preceding the Agincourt expedition. In December 1417, Beaufort was named cardinal. It is uncertain to what extent Wichester’s advancement in rank was due to his own aspirations or achievements and services to the crown. He forfeited Henry’s trust and favour, was excluded from politics, and in contrast to his power and influence wielded from 1413 to 1417, his position in closing years of reign represented a striking reversal of fortune. Following the death of Henry V, there were no written instructions about government and Beaufort was not prepared to render to Henry’s two brothers the subservience exacted from him by Henry. He had disputes with Duke Humphrey from 1424 to 1427. From 1430 to 1431 Beaufort devoted himself to planning and financing Henry VI's journey to Paris for coronation and planned in the defence of Lancastrian France. From 1432 to 1435 Beaufort faced enmity of both the Dukes of Bedford and Gloucester. Beaufort possessed a keen intelligence and could speak with eloquence, but he showed little appreciation of the intellectual outlook of the humanists with whom he came into contact in Italy. He died in 1447 after retiring in 1443.

Reading:

Wentersdorf, Karl P. "The Winchester Crux in the First Folio's 1 Henry VI." Shakespeare Quarterly 57:4 (Winter 2006). 443-49.

Source: Harriss, G.L. ‘Beaufort, Henry (1375?–1447)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/1859, accessed 28 April 2015]

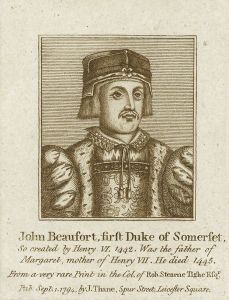

John Beaufort was duke of Somerset from 1404-1444, second son of John Beaufort. He succeeded to the earldom of Somerset on the death of his elder brother, Henry. He was knighted by Henry V at Rouen in 1420. John was made prisoner at the battle of Bauge. Negotiations for Somerset’s release in exchange for the duke of Bourbon between 1428 and 1430 came to nothing. An agreement was not reached until 1438, leaving Somerset impoverished and only on his mother’s death in 1439 did he secure the Beaufort and Holland lands. In November 1439 Somerset returned to England where his claim to succeed Warwick as lieutenant-general was being pressed by his uncle, Henry, Cardinal Beaufort (d. 1447), against the claim of Humphrey, duke of Gloucester. Somerset's supreme military command in France was temporarily renewed and early in 1440 he led a substantial force of 2100 men to Normandy, financed by loans from the cardinal. He died at Corfe and Wimborne where he died in May of 1444 (Harriss, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).

Source: Harriss, G.L. ‘Beaufort, John, duke of Somerset (1404–1444)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/1862, accessed 28 April 2015]

Richard Plantagenet, or Richard of York

Richard of York, third duke of York, magnate and claimant to the English throne, was the only son of Richard of Conisburgh, fourth earl of Cambridge and Anne Mortimer. He is descended from Edward III through both his parents, his father the son of that king’s fourth son, Edmund Langley, and his mother the great-granddaughter of Edward’s second son, Lionel of Antwerp. His distinguished ancestry provided the foundation for the explosive participation in the politics of the 1450s. In October 1460, he attempted to seize the throne on the grounds that his descent from Lionel of Antwerp made him rightful king in place of Henry VI. The attempt failed, and York died a few months later at the battle of Wakefield, but the claim, of course, lived on to provide the basis for Edward IV’s succession in March 1461. Historically, he would be 11 at the beginning of Shakespeare’s Henry VI, pt. 1.

Reading:

Crawford, Anne. The Yorkists: The History of a Dynasty. London: Continuum, 2007. Porter Library.

Johnson, P.A. Duke Richard of York 1411-1460. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1988. Porter Library.

Source: Watts, John. ‘Richard of York, third duke of York (1411–1460)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/23503, accessed 28 April 2015]

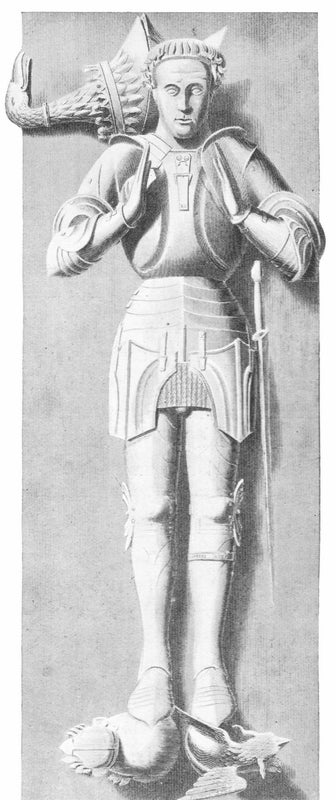

Earl of Warwick, Richard Beauchamp

Richard Beauchamp was born at Salwarp, Worcestershire, in January 1382. Beauchamp identified himself closely with the Lancastrian kings throughout his career. In May of 1410 he was named royal councillor. The accession of Warwick's master, Henry V, in 1413 immediately gave him a new pre-eminence. He was frequently employed on diplomatic missions throughout the reign. He was present at Henry's death at Vincennes on 31 August and named an executor of his will, and accompanied the body of the king back to England at the end of October 1422. In December 1422 he became a member of Henry VI's minority council. The records suggest that until about mid-1425 he was frequently in England and much about the young king, but, at the same time, he was captain of Rouen by early 1423 and of Calais not long after. He returned to England in March 1428 and in June he was made personal governor and tutor of Henry VI; in this role in November 1429 he famously bore the young king in his arms to his coronation. There ensued a period of almost continuous residence in England until 1436, broken only by service on the coronation expedition and subsequent campaign in 1430–32. He died in Rouen on April 30th, 1439

Source: Carpenter, Christine. ‘Beauchamp, Richard, thirteenth earl of Warwick (1382–1439)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2013 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/1838, accessed 28 April 2015]

Source: Curry, Anne. ‘Montagu, Thomas , fourth earl of Salisbury (1388–1428)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/18999, accessed 28 April 2015]

William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk

Reading:

Williams, Gwyn. "Suffolk and Margaret: A Study of Some Sections of Shakespeare's Henry VI." Shakespeare Quarterly 25 (1974): 310-22.

Source: Watts, John. ‘Pole, William de la, first duke of Suffolk (1396–1450)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2012 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/22461, accessed 28 April 2015]

Lord Talbot, Constable of France

Reading:

Chernaik, Warren. "1 Henry VI: brave Talbot and his adversaries." The Cambridge introduction to Shakespeare's history plays. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Porter Library.

Pearlman, E. "Shakespeare at Work: The Two Talbots." Philological Quarterly 75:1, Winter 1996

Riddell, James A. "Talbot and the Countess of Auvergne." Shakespeare Quarterly. 28:1 (Winter 1977): 51-57.

Rodgers, Joel. "Talbot, Incorporated." Renaissance Shakespeare/ Shakespeare Renaissances: Proceedings of the Ninth World Shakespeare Congress. Eds. Martin Procházka, Michael Dobson, Andreas Höfele, and Hanna Scolnicov. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Woodcock, Matthew. "John Talbot, Terror of the French: A Continuing Tradition." Notes and Queries 51 (2004): 249-51.

Significant Battles: The Battle of Castillon

Source: Pollard, A.J. ‘Talbot, John, first earl of Shrewsbury and first earl of Waterford (c.1387–1453)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/26932, accessed 28 April 2015]

John Talbot, Lord Talbot’s son

Source: Wikipedia

Edmund (V) Mortimer was the fifth Earl of March, magnate and potential claimant to the English throne. He was a descendent from Edward III and threatened the usurping Lancastrian dynasty in 1399. Following Richard II’s deposition by Henry Bolingbroke in 1399, rebels periodically publicized Mortimer’s claim. Though plausible, this was weakened by descent through a female—his father's mother, Philippa, daughter of Lionel of Clarence, Edward III's second surviving son—and by Edmund's youth; nevertheless, Henry IV placed this potential rival under strict supervision. As he grew older, Edmund's future merited special consideration. In February of 1408 his marriage was granted to Queen Joan, on condition that he could marry only with the king's assent and the council's advice. The death of Henry IV may have prompted renewed murmurings about Edmund Mortimer's claim. Nevertheless, Henry V released him from custody and knighted him on the eve of his coronation; in parliament in June he was declared of age and allowed to inherit his estates. After Henry V's funeral, Mortimer was appointed one of the new king's councillors in 1422. In 1424 Henry VI's uncle, Humphrey, duke of Gloucester, expressed unease at the size of Edmund Mortimer's retinue and this may explain why Mortimer was appointed the king's lieutenant in Ireland in March 1423, though a visit to his ravaged estates there was long overdue. Ships were commissioned for his journey in 1423–4, but not until the autumn of 1424 did he set sail. He died of plague in 1425 at his castle of Trim.

Source: Griffiths, R.A. ‘Mortimer, Edmund (V), fifth earl of March and seventh earl of Ulster (1391–1425)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/19344, accessed 28 April 2015]

Sir John Fastolf was a soldier and landowner, born into a minor gentry family in Norfolk. He served under the duke of Clarence in Ireland and then in Acquitaine (1412-3) as deputy constable of Bordeaux and captain of Soubise and Veyres in 1413-14. He returned in 1415 and joined Henry V’s expedition in 1415 and fought at Agincourt. It was with Clarence and Exeter that he served from 1417-21. During Henry V's absence in England, the duke of Exeter, as governor of Paris, made Fastolf captain of the Bastille de St Antoine which he defended during the disturbances after the battle of Baugé in 1421. Following Henry V's death and Exeter's return to England he, with other professional captains, formed a group under the command of the regent, John, duke of Bedford, which carried forward the momentum of the conquest. Appointed lieutenant in Normandy for a year in 1422, Fastolf was employed in clearing the region to the south-west of Paris, and held captaincies at Fresnay-le-Vicomte and Alençon. He distinguished himself in Bedford's victory over the Dauphinist–Scottish force at Verneuil in August and was made a knight-banneret in 1424 and knight of the Garter in 1426. Fastolf returned to England in 1439 rich, honoured, well connected, and in full mental and physical vigour, but instead of the respect, recognition, and ease that he anticipated he experienced twenty years of hostility and persecution that almost brought his ruin. His fortunes were caught up in the contentions of domestic politics not because he was actively involved in them, but because his background linked him to the opponents of the government and his lack of an heir attracted the covetous and unscrupulous. He died in 1459 just as the civil war began.

Source: Harriss, G.L. ‘Fastolf, Sir John (1380–1459)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/9199, accessed 29 April 2015]

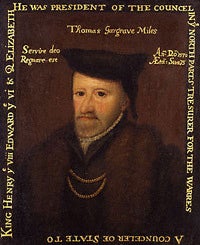

Sir Thomas Gargrave (d. 1428) was a knight, Master of the Ordnance and Marshall of the English army of Henry VI in France and killed during the Siege of Orléans along with the Earl of Salisbury. Edward Hall in Hall’s Chronicle explains that on 26 October 1428 a cannon shot shattered the iron grate of the observation tower where Gargrave and Salisbury were standing. Gargrave died two days later and Salisbury died ten days later. Gargrave’s father was Sir John Gargrave, Knight and Master of the Ordnance under Henry V and Governor in France.

Source: Archer, Ian W. ‘Gargrave, Sir Thomas (1494/5–1579)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/10383, accessed 29 April 2015]

Woodville's spouse was Elizabeth Joan Bedelgate (1390–1448).

The couple had at least two children, Sir Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers (1408–1469), and Joan Woodville (1409–1462), wife of Sir William Haute.

Their grandchild, through Earl Rivers and his wife was Elizabeth Woodville, Queen Consort to King Edward IV of England, and ancestor of all English ruling monarchs from 1509 onwards and Scottish ruling monarchs from 1513 onwards.

Source: Hicks, Michael. ‘Woodville , Richard, first Earl Rivers (d. 1469)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/29939, accessed 8 May 2015]

Unnamed in Shakespeare, but historically, Mayor of London at the time of the play would have been John Coventry, a mercer ("John Couentrie, Mercer"Stowe 2.187-88).

A new mayor was elected from within the business community of the City of London every year, with responsibility to impose the rule of the law within the City's bounds - the City being a relatively small part of what is now central London, separate from and often politically opposed to both Westminster, the seat of government, and Southwark, Winchester's base and, later, the location of the theatres themselves.

Source: Burns, Edward. p111.

Sir William Glansdale

Sir William Lucy

Bassett

Vernon

Exeter (conflated with Warwick)

THE FRENCH

Source: "Rene I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 29 Apr. 2015

Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England

Reading:

Dockray, Keith. Henry VI, Margaret of Anjou and the Wars of the Roses : a sourcebook. Stroud: Sutton P, 2000. Porter Library.

Hookham, Mary Ann.The life and times of Margaret of Anjou, queen of England and France; and of her father René "the Good", king of Sicily, Naples, and Jerusalem. With memoirs of the houses of Anjou. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1872.

Munro, Cecil (Ed.). Letters of Queen Margaret of Anjou and Bishop Beckington and others : written in the reigns of Henry V and Henry VI. From a ms. found at Emral in Flintshire. London: Camden Society, 1863.

Source: Dunn, Diana E.S. ‘Margaret (1430–1482)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.uwaterloo.ca/view/article/18049, accessed 28 April 2015]

Source: "Jean d'Orleans, comte de Dunois". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 29 Apr. 2015

Source: "Philip III". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 29 Apr. 2015

Joan of Arc (1412-1431), also known as the Maid of Orleans or La Pucelle d’Orleans, was a national heroine of France, a peasant girl who believed she was acting under divine guidance and led the French army in a momentous victory at Orleans that repulsed an English attempt to conquer France during the Hundred Years’ War. She joined the French force at the age of seventeen, and won over the leadership with her bravery and ability in battle. Joan featured in a number of significant excursions for the French, until 1430, when she was captured by a Burgundian force loyal to the occupying English force. After several attempts to escape, Joan was moved to Rouen, where she was tried and convicted of heresy and witchcraft. Joan was burned at the stake on 30 May 1431 at the age of 19. She was canonised in 1920, and is today one of France's patron saints.

Reading:

Castor, Helen. Joan of Arc: A History. London: Faber and Faber, 2014.

Fraioli, Deborah. "The Literary Image of Joan of Arc." Speculum 56:4 (1981): 811-38.

King, Annie Papreck. "Shaw's Saint Joan and Shakespeare's Joan la Pucelle." Text and Presentation Supplement 4 (2007): 109-21.

Paxson, James J. "Shakespeare's Medieval Devils and Joan la Pucelle." in Henry VI: Critical Essays, ed. Thomas A. Pendleton. New York:Routledge, 2001. 127-55.

Rossini, Manuela S. "The Sexual/Textual Impossibility of Female Heroism in the First Tetralogy." Shakespeare Yearbook 14 (2004): 45-78.

Schwarz, Kathryn. "Fearful Simile: Stealing the Breech in Shakespeare's Chronicle Plays." Shakespeare Quarterly 49:2 (Summer 1998). 140-67.

Sheppard, Philippa. "The Puzzle of Pucelle or Pussel: Shakespeare's Joan of Arc Compared with Two Antecedents." Renaissance Medievalisms [F]: 191-209.

Spiller, Ben. "'She and the Dolphin have been iugling': The Ambiguous Gender of Joan la Pucelle in Henry VI Part 1." Renaissance Journal 1, no. 5 (2002): 17-19.

Stanton, Kay. "A Presentist Analysis of Joan, la Pucelle: 'What's past and what's to come she can descry.'" Presentism, Gender, and Sexuality in Shakespeare [F]: 103-21.

Waltonen, Karma. 'Saint Joan: From Renaissance Witch to New Woman.' Shaw: The Annual of Bernard Shaw Studies. 24 (2004): 186-203.

Significant Battles: The Siege of Orleans

Significant Battles: The Death of Joan of Arc