By

John

Motz

While

we

take

for

granted

bright

electric

lighting

for

our

vehicles

and

in

our

homes,

over

100

years

ago

it

was

the

work

of

a

little-known

Canadian

inventor

which

helped

pave

the

way

for

a

type

of

illumination

which

outshone

electric

light.

The

light

was

the

bright

flame

of

burning

acetylene

and

the

Canadian

inventor

was

Thomas

Leopold

(“Carbide”)

Willson.

Acetylene

gas

is

produced

when

water

is

applied

to

calcium

carbide,

and

Willson

was

the

inventor

of

an

inexpensive

process

for

making

calcium

carbide.

Willson

was

a

19th-century

inventor,

entrepreneur

and

wheeler-dealer

in

the

style

of

Thomas

Edison,

but

without

the

latter’s

fame

and

business

acumen.

The

son

of

an

unsuccessful

farmer

and

manufacturer,

Willson

was

born

in

1860

on

a

farm

near

Princeton,

Ontario.

When

Willson’s

father

lost

the

farm,

he

moved

his

family

to

the

United

States

to

pursue

a

manufacturing

venture.

When

this

failed,

he

returned

to

Canada

in

about

1872,

settling

in

Hamilton.

“Carbide

Willson”

in

about

1914.

(From

Wikipedia)

The

young

Willson

showed

an

early

interest

in

electricity.

At

age

19

he

was

apprenticed

to

a

Hamilton

blacksmith,

at

whose

shop

he

constructed

a

steam

driven

dynamo:

one

of

Canada’s

first.

Willson

was

unable

to

commercialize

his

dynamo

and

electric

light

system

in

Canada,

so,

in

1882,

he

moved

to

New

York

City,

where

he

worked

as

an

inspector

of

electrical

installations,

and

continued

to

work

on

his

own

projects.

He

was

a

prolific

inventor,

patenting

arc

and

incandescent

lights,

and

modifications

to

his

dynamo.

While

investigating

commercial

applications

for

his

dynamo,

Willson

experimented

with

the

smelting

of

metals

in

electric

furnaces.

In

one

of

these

experiments,

in

1891,

while

trying

to

produce

metallic

calcium

from

lime

(calcium

oxide)

and

carbon

(in

the

form

of

powdered

coal)

in

an

electric

furnace,

he

accidentally

made

an

unknown

substance,

which

turned

out

to

be

calcium

carbide.

Lumps

of

Calcium

Carbide.

(From

Wikipedia)

Since

the

application

of

water

to

calcium

carbide

produces

acetylene

gas,

Willson

worked

to

commercialize

his

discovery,

by

developing

an

economically-viable

industrial

process

for

producing

calcium

carbide,

and

set

about

looking

for

a

market.

Acetylene

burns

with

a

bright

white

light,

of

superior

quality

to

the

illumination

from

contemporary

coal

gas

and

incandescent

lights.

The

first

market

for

calcium

carbide

was

as

an

acetylene

generator

in

lights

for

such

things

as

lighthouses,

floodlights,

railway

coaches,

navigation

aids,

bicycle

headlights

and

miners’

headlamps.

Carbide

lamps

were

later

used

in

early

cars

and

motorcycles.

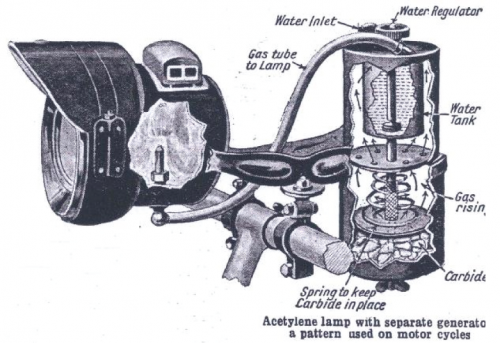

A

carbide

motorcycle

headlight

(above)

and

a

schematic

illustration

of

how

it

worked. (From

douglasmotorcycles.net)

(From

www.rexophone.com)

In

these

applications,

water

was

dripped

on

calcium

carbide

to

produce

acetylene

gas

(see

illustration),

which

fueled

the

lamp

and

was

burned

to

produce

light.

This

technology

could

also

be

used

in

homes,

where

a

carbide-fueled

acetylene

generator

was

located

in

the

basement

and

the

gas

produced

piped

to

lights

throughout

the

house.

These

acetylene

generators

could

be

dangerous

though,

with

sources

suggesting

they

be

kept

in

a

separate

building,

because

of

the

explosion

hazard,

and

advising

the

homeowner

to

extinguish

his

cigar

before

refilling

the

calcium

carbide

hopper.

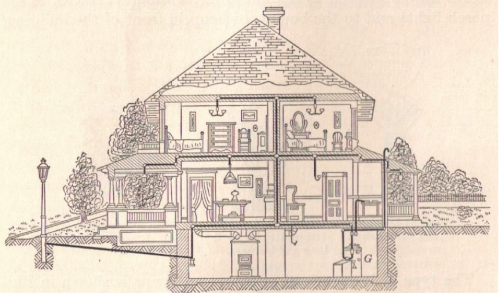

A

domestic

acetylene

system,

showing

the

carbide-fueled

generator

in

the

basement

and

the

piping,

which

distributed

the

gas

throughout

the

house.

(From

rexohone.com)

It

wasn’t

until

1903

that

the

most

important

use

of

acetylene,

in

oxyacetylene

welding

and

cutting,

was

developed.

In

1895

Willson

sold

his

American

patents

to

a

syndicate,

which

would

later

become

Union

Carbide,

and

returned

to

Canada.

There,

he

constructed

carbide

plants

in

Merritton,

near

St.

Catharines,

Ontario,

Ottawa

and

Shawinigan,

Quebec.

After

moving

to

Ottawa

in

1901,

Willson

became

a

well-known

local

figure

and

was

the

first

person

in

that

city

to

own

an

automobile.

He

continued

to

experiment,

working

on

everything

from

new

uses

for

carbide

to

the

telephone.

He

received

the

first

McCharles

prize,

from

the

University

of

Toronto,

in

1909

for

his

discoveries.

He

developed

an

inexpensive

method

for

making

fertilizer,

but

lost

his

patents

for

the

process

and

some

other

assets

to

an

American

investor

after

a

business

setback

in

an

attempt

to

set

up

a

fertilizer

plant.

Willson

was

a

keen

industrialist:

He

tried

to

start

a

pulp

and

paper

business

in

Quebec.

After

his

failure

in

the

fertilizer

business,

he

set

about

trying

to

develop

hydroelectric

dams,

railways,

and

carbide,

pulp

and

paper,

and

fertilizer

factories

in

Newfoundland

and

Labrador,

but

died

of

a

heart

attack

in

New

York

City

in

1915,

while

trying

to

raise

funds

for

those

projects.

Carbide

lamp

used

by

miners

and

for

exploring

caves.

(From

Wikipedia)