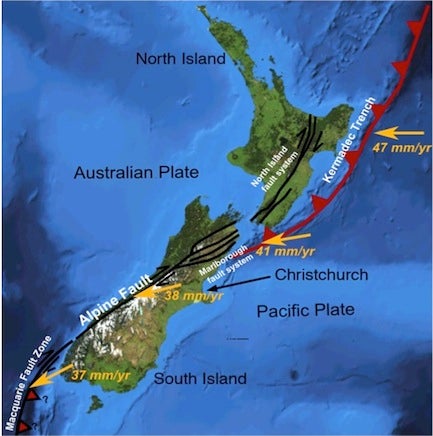

Figure

3:

Major

New

Zealand

faults

(modified

from

Wikipedia).

Due

to

these

plate

movements

there

are

frequent

deep

earthquakes

in

the

north

and

southwest,

were

subduction

is

occurring,

and

shallow

earthquakes

along

the

Alpine

Fault.

Although

the

Christchurch

area

(Canterbury

region)

had

been

stable

for

a

long

time,

there

are

many

faults

underlying

the

area

and

a

1991

report

by

the

government

Earthquake

Commission

concluded

that

earthquakes

as

damaging

as

the

February

22,

2011

event

would

occur

on

average

every

55

years.

The

last

major

earthquake

to

affect

the

region

was

the

1922

Motunau

earthquake.

On

September

4,

2010

Christchurch

was

rocked

by

a

magnitude

7.1

earthquake

centred

38

km

west

of

the

city,

at

a

depth

of

10.5

km.

While

this

quake

caused

a

great

deal

of

damage,

no

lives

were

lost,

partly

because

it

occurred

at

4:35

am,

when

most

people

were

at

home,

partly

because

New

Zealandʼs

strict

building

codes

have

resulted

in

relatively

earthquake-resistant

structures,

and

because

the

quake

was

relatively

distant

from

the

city

and

fairly

deep.

A

magnitude

4.9

aftershock

at

10:30

am

on

December

26

caused

damage

out

of

proportion

to

its

size

because

it

was

shallow,

at

5.12

km

deep,

and

only

2.1

km

from

the

city

centre.

Earthquakes

are

categorized

using

the

Richter

Magnitude

Scale

in

which

each

increase

in

magnitude

means

the

ground

is

shaking

ten

times

as

hard.

For

instance,

a

magnitude

5.0

quake

shakes

ten

times

harder

than

a

magnitude

4.0

tremor.

How

strong

a

quake

feels

at

any

particular

location

is

dependent

not

only

on

the

magnitude,

but

the

distance

from

the

epicentre

(the

surface

location

above

the

focus

of

the

quake)

and

depth

of

the

quake.

Logically

enough,

a

shallow

nearby

tremor

is

worse

than

a

deeper

more

distant

one

of

the

same

magnitude.

The

magnitude

6.3

February

22

earthquake

that

we

experienced

was

centred

6.8

kilometres

from

the

city

centre,

at

a

depth

of

5.9

km.

The

proximity

of

this

quake,

combined

with

the

high

intensity

of

the

ground

movement,

contributed

to

its

destructive

force.

Ground

acceleration

on

February

22

was

measured

as

high

as

2.2

times

the

force

of

gravity

(2.2g),

compared

to

a

high

measured

value

of

1.26g

on

September

4.

Furthermore,

the

ground

motion

was

a

combination

of

up

and

down

and

side

to

side

shaking,

making

it

almost

impossible

for

buildings

to

survive.

Also,

many

buildings

had

already

been

weakened

by

previous

shocks

and

couldnʼt

stand

up

to

any

more

shaking.

The

timing

of

the

quake

contributed

to

the

large

number

of

deaths,

since

it

occurred

during

lunch

hour

on

a

weekday,

when

many

people

were

in

the

central

business

district.

Extensive

damage

was

also

caused

by

liquefaction.

In

this

process,

loose,

saturated

sediment

loses

all

its

strength

and

behaves

like

a

liquid

after

it

receives

a

shock.

Large

areas

of

the

Christchurch

are

underlain

by

this

type

of

sediment,

which

underwent

liquefaction

at

the

time

of

the

September

and

February

quakes,

resulting

in

buildings

being

undermined,

roads

collapsing

and

damage

to

80%

of

the

water

and

sewage

systems.

The

cost

of

post

earthquake

reconstruction

has

been

estimated

at

$12-billion.

With

about

376,000

people,

Christchurch

is

New

Zealandʼs

second

largest

city

and

comprises

about

8.6%

of

the

countryʼs

population.

In

terms

of

the

proportion

of

the

countryʼs

population

affected,

the

Christchurch

earthquake

is

approximately

analogous

to

a

similar

catastrophe

hitting

Toronto.

For

Heather

and

I,

and

the

two

friends

who

took

us

in,

the

loss

of

the

water

infrastructure

was

the

most

immediate

concern.

Electricity

had

been

restored

where

we

were

staying

by

9:00

pm,

but

with

no

drinking

water

and

toilet

facilities

were

a

major

concern.

The

four

of

us

had

a

total

of

three

litres

of

water,

which

wouldnʼt

last

long.

Fortunately

for

us,

it

rained

that

night

and

we

were

able

to

collect

a

barrel

of

clear

rainwater,

which

only

had

to

be

boiled

before

use.

Toilet

facilities

were

more

of

a

challenge,

with

a

hole

in

the

ground

or

a

bucket

filling

the

bill.

It

was

a

lesson

in

how

reliant

we

are

on

city

utilities

to

keep

us

from

regressing

to

a

primitive

lifestyle.

Christchurch

continued

to

be

rocked

by

aftershocks

so,

after

three

days,

we

left

to

stay

with

other

friends

in

the

town

of

Ashburton,

about

90

km

southwest

of

Christchurch.

Ashburton

was

largely

unaffected

by

the

earthquakes

and

had

full

services

and

a

welcome

lack

of

aftershocks.

Because

of

the

hasty

departure

from

our

apartment,

most

of

our

possessions

were

still

there.

Unfortunately,

our

place

was

inside

the

cordon

maintained

by

the

police

and

army

for

public

safety

and,

therefore,

was

off

limits

for

all

but

essential

personnel.

Daily

calls

to

the

police

confirmed

that

no

one

was

being

allowed

in.

By

this

point,

ten

days

after

the

earthquake,

we

were

eager

to

return

to

Canada

so

we

wouldnʼt

be

a

burden

to

our

friends

for

longer

than

absolutely

necessary.

We

had

heard

a

rumor

that

some

people

were

being

allowed

access

to

their

homes

in

the

cordoned-off

area,

so

we

decided

to

take

a

chance.

On

March

4

we

showed

up

at

one

of

the

checkpoints

with

a

phone

bill

to

prove

our

address,

and

our

passports

for

ID,

and,

much

to

our

surprise,

were

allowed

to

go

to

our

place

unescorted

to

retrieve

our

belongings.

Inside

the

cordon

the

city

was

eerily

quiet,

with

few

vehicles

and

many

roads

damaged

by

the

quake.

Abandoned

cars

made

the

place

feel

like

a

ghost

town.

We

reached

our

building

and

found

it

apparently

intact,

and

only

slightly

damaged

but,

half

a

block

away,

Colombo

Street

was

a

scene

of

devastation

that

looked

like

a

war

zone

(Figures

4

and

5).

Figure

4:

The

corner

of

Colombo

and

St.

Asaph

streets,

half

a

block

from

our

building.

Our

building

had

a

yellow

sticker,

meaning

it

might

have

been

unsafe

to

enter

(kind

of

like

saying

this

gun

may

be

loaded),

so

we

went

in

with

some

trepidation,

concerned

that

an

aftershock

might

bring

it

down.

Inside

(Figure

6),

despite

the

fact

that

most

things

had

fallen

off

the

walls,

or

tipped

over,

and

much

of

the

kitchen

ware

had

fallen

out

of

the

cupboards,

the

place

seemed

to

be

structurally

intact,

with

some

cracks

in

the

walls

being

the

only

apparent

damage.

We

hurried

to

remove

our

belongings

from

the

apartment

and

load

them

into

our

rented

SUV,

which

ended

up

stuffed

full

to

the

roof.

As

we

were

finishing,

a

military

vehicle

with

two

soldiers

stopped

to

see

what

we

were

doing.

One

soldier

took

a

look

at

the

yellow

sticker

on

the

building

and

told

us

to

get

out

as

quickly

as

possible.

Once

we

retrieved

our

things

we

were

able

to

rebook

our

airline

tickets,

to

depart

two

weeks

earlier

than

planned.

We

then

took

a

week-long

trip

to

the

north

island,

which

had

been

planned

before

the

earthquake.

We

returned

to

Christchurch

briefly,

then

left

for

Canada

on

March

16.

Figure

6:

Our

apartment

after

the

earthquake.

For

Heather

and

I,

our

earthquake

experience

ended

when

the

wheels

of

the

Air

New

Zealand

Boeing

777

left

the

ground

in

Auckland,

bound

for

Vancouver.

But,

for

the

people

of

Christchurch,

the

ramifications

of

the

disaster

continue.

Much

of

the

downtown,

called

the

Red

Zone,

is

still

cordoned

off,

meaning

access

is

limited

for

both

business

and

residents.

No

one

can

live

or

work

in

this

area.

Many

buildings

have

red

stickers,

which

means

they

are

unsafe

and

may

have

to

be

demolished.

Thousands

of

people

are

still

either

homeless,

or

living

in

badly-damaged

houses

that

need

to

be

rebuilt.

After

returning

to

Canada,

we

were

informed

that

our

building

had

been

red

stickered

and

may

have

to

be

partially

demolished,

so

the

permanent

residents,

our

friends,

have

had

to

find

alternate

accommodation

for

the

foreseeable

future.

We

feel

fortunate

to

have

come

through

the

experience

unscathed,

and

that

none

of

our

friends

were

harmed.