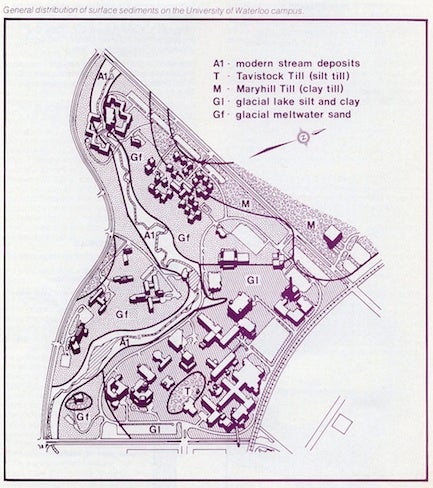

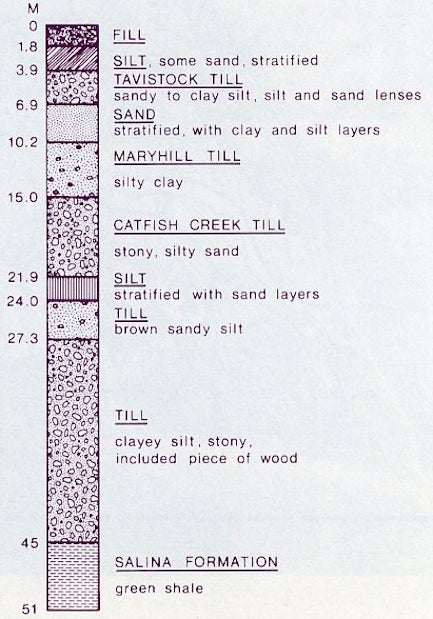

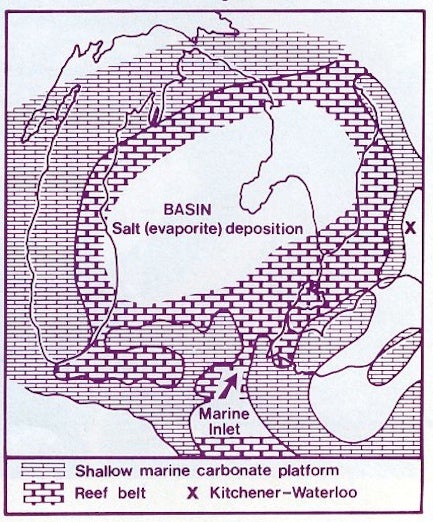

Saturday, December 24, 2011

What

on

Earth:

Volume

7

2011

P.F.

Karrow

In

natural

science,

the

frontier

of

the

unknown

is

never

far

away.

One

of

the

frontiers

lies

below

our

feet.

What

lies

below

the

surface

of

the

ground?

How

did

the

University

campus

get

to

be

so

hilly?

In

May,

1976,

a

hole

was

drilled

by

the

Department

of

Earth

Sciences

drilling

rig

beside

the

Chemistry

Building,

in

order

to

get

a

glimpse

into

the

unknown

below

us.

Although

when

the

various

buildings

were

constructed

exposures

and

borings

were

made,

these

generally

extended

to

only

shallow

depths

of

3

to

10

metres

and

deposits

still

farther

down

remained

concealed

and

unknown.

A

few

test

holes

had

also

been

put

down

to

test

water

supplies

but

no

soil

samples

had

been

obtained

from

these

holes.

From

these,

however,

we

estimated

that

the

depth

to

rock

was

about

30

metres

under

the

Chemistry

Building,

and

so

we

made

plans

to

get

a

continuous

core

sampling

of

the

materials

down

into

bedrock.

The

sequence

of

deposits

encountered

in

the

hole

reveals

part

of

the

geological

history

of

the

area.

Together

with

other

available

information,

an

interesting

story

can

be

put

together.

The story of the bedrock

The

solid

rock

encountered

directly

below

the

campus

is

green

shale

and

brown

dolomite

of

the

Salina

Formation.

Southeast

of

us,

near

Paris,

this

same

rock

formation

is

exposed

in

the

banks

of

the

Grand

and

Speed

Rivers.

Paris

got

its

name

from

gypsum

deposits

formerly

mined

from

the

Salina

Formation

(for

“Plaster

of

Paris”).

At

Goderich,

rock

salt

is

obtained

from

the

same

formation.

These

evaporite

minerals

tell

us

that

the

Salina

Formation

was

formed

in

a

shallow

arm

of

the

sea

that

then

covered

much

of

the

eastern

United

States.

The

age

of

these

rocks

is

about

400

million

years.

Green

shale

of

the

Salina

Formation

was

penetrated

for

about

6

metres

by

the

1976

boring.

We

know

from

rocks

laid

down

elsewhere

that

a

long

span

of

time

is

unrecorded

by

the

rock

succession

at

this

location.

Presumably

some

rocks

were

formed,

but

were

later

eroded

away.

The

traces

of

old

stream

valleys

cut

into

the

rock

surface

are

revealed

by

water

well

records,

which

show

that

various

“buried

valleys”,

completely

filled

and

concealed

by

much

younger

glacial

deposits,

cross

the

area.

The

missing

interval

here

spans

the

period

from

400

million

years

ago,

to

several

tens

of

thousands

of

years

ago.

The story of the glacial deposits

The

deposits

overlying

and

concealing

the

bedrock

are

mainly

derived

from

glaciations.

More

specifically,

they

are

a

mixture

of

all

sizes

of

material

from

clay

to

boulders,

called

till,

laid

down

directly

by

the

ice

itself.

The

several

layers

of

different

kinds

of

till

represent

several

advances

of

the

ice

over

the

area.

In

all,

five

till

layers

were

encountered

in

the

borehole,

as

shown

in

the

accompanying

sketch.

At

a

depth

of

about

42

metres,

in

the

lowest

till

layer,

a

small

piece

of

spruce

wood

was

found.

This

tells

us

that

the

ice

which

deposited

the

till

overrode

the

vegetation

which

grew

earlier

in

the

area.

We

don’t

know

the

age

of

the

wood

(it

is

too

small

for

radiocarbon

dating)

but

it

could

be

50,000

to

100,000

years

old.

We

know

that

the

middle

layer

of

till

(Catfish

Creek

Till)

was

laid

down

by

a

strong

ice

advance

about

18,000

years

ago,

which

covered

all

of

Ontario

and

the

northern

States.

Melting

back

about

16,000

years

ago

temporarily

uncovered

this

area,

but

it

was

covered

by

ice

again

about

15,000

years

ago.

About

this

time

melt-waters

from

the

glaciers

were

building

up

large

accumulations

of

gravel

and

sand,

forming

the

Waterloo

sandhills.

We

are

situated

on

the

eastern

edge

of

these

rolling

sandhills

and

fine

sand

of

this

origin

is

found

exposed

in

the

slopes

south

of

Columbia

Street.

Ice

flowing

from

the

Georgian

Bay

area

and

Lake

Ontario

area

both

covered

this

vicinity

one

time

or

another

near

14,000

years

ago

and

then

finally

retreated.

The

next

ice

readvance

from

the

east

only

reached

the

east

edge

of

Waterloo

but

melt-waters

eroded

into

the

older

deposits

and

gave

birth

to

the

various

branches

of

Laurel

Creek.

Remnants

of

the

Tavistock

Till

sheet,

brought

here

by

the

last

advance

of

the

Georgian

Bay

ice

are

to

be

found

on

the

tops

of

the

higher

areas

near

St.

Paul’s

College,

along

Columbia

Street

and

at

the

Graduate

House

and

Minota

Hagey

Residence.

Thorough

the

thousands

of

years

following,

the

valleys

have

deepened

as

Laurel

Creek

continued

to

cut

down.

In

some

places

erosion

was

hindered

by

the

glacial

deposits

and

the

streams

became

sluggish

and

swampy.

The

climate

became

warmer,

and

the

spruce

forest

was

succeeded

by

pine

forest,

then

later

by

the

hardwoods.

Erosion

continues

today

along

Laurel

Creek

however.

During

construction

of

the

Village

residences,

disturbed

soil

around

the

excavations

was

washed

into

the

stream

channel

by

heavy

rains.

This

sediment

was

carried

down

to

the

pond

at

Conrad

Grebel

College,

where

it

accumulated

in

a

delta.

As

the

delta

grew

rapidly,

it

had

to

be

dredged

out

several

times

by

dragline

to

prevent

filing

of

the

pond.

With

cessation

of

construction,

and

landscaping,

sediment

load

in

the

stream

has

greatly

diminished

and

a

more

stable

pond

environment

has

resulted.

Further information on the local geology may be gained from the following:

Chapman,

L.J.

and

Putnam,

D.F.,

1966,

The

physiography

of

southern

Ontario;

2nd

edition,

University

of

Toronto

Press.

386

p.

Isherwood,

A.E.,

1976,

Quaternary

geology

and

soil

conditions,

University

of

Waterloo

campus;

M.Sc.

project

report.

Dept.

of

Earth

Sciences.

59p.

Karrow,

P.F.,

1971,

Quaternary

geology

of

the

Stratford-Conestoga

area,

Ontario;

Geol.

Surv.

Can.

Paper

70-34.

11p.