Something missing from the Hub?

Is there some research you need to illuminate your character?

Do you have any questions about the production or the period?

This page will be maintained throughout the rehearsal period, and any questions asked will be answered and posted here.

Jump to the Latest Updates (May 31 2015)

Email the Dramaturg:

To contact Dr. Toby Malone click here

I will endeavour to have all questions addressed and posted within 24 hours.

Questions Asked and Answered

Q: Is the Falstaff from Henry the Sixth the same Falstaff as from the other Shakespeare plays?

A: No, since the John Falstaff who is friends with Prince Hal in Henry the Fourth parts One and Two dies at the beginning of Henry the Fifth. In fact, Falstaff's first appearance in Shakespeare (as such) is in this cameo performance in Henry the Sixth, Part One. Based on a historical English knight (see character biographies), this Falstaff is not the same man as the famous fat knight. When Shakespeare first wrote Henry the Fourth, Falstaff was called John Oldcastle, based on another historical figure. Protestations from Oldcastle's family led to a hasty name change, and the already-used name of Falstaff was close to hand.

Q: Who was Henry supposed to marry before Margaret?

A: Henry was supposed to marry Isabelle, daughter of the Count of Armagnac, to solidify the slipping Armagnac position in France.

A series of questions on Worship and the Bible:

Q: What versions of the Bible were in circulation (orally in churches or in print) in 1592 in England?

A: See a more detailed history of Bible publication in the answer below, but the predominant versions of the Bible that circulated in England in 1592 were the Geneva Bible, and to a lesser extent, the Bishop's Bible, based on the Henry VIII-era Great Bible (sometimes referred to as the 'rough draft for the King James Bible'). Some earlier versions still existed, but the Geneva Bible's position as a Study Bible beloved by the people, meant that was predominant.

Q: Were weekly readings prescribed by the Common Book of Prayer in English or in Latin?

A: The Book of Common Prayer was introduced into England by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, as the cornerstone to the English reformation under King Henry VIII. Cranmer did not write the book, but presided over a conclave of men who constructed the work to ensure that a common vernacular was followed in the new Anglican church. The readings were notably in English, which was an immediate indicator of a break from the Latin-based Catholic writings that preceded it.

An exhaustive (if aging) account of the history of the Book of Common Prayer can be found here.

Also, here is a strong article on the ways in which the BCP differed from its Catholic predecessors.

Q: What English versions of the Bible were in circulation before the King James (1604)?

A: The first recorded English-language Bibles date from the late fourteenth century, when theologian and professor John Wycliff, who, along with his followers, produced dozens of English-language versions of the scriptures. This was not well-received by the Pope, but the idea of an English-language Bible began to take root as a way of allowing the common man to read the Word of God. The advent of the Gutenberg Press in the sixteenth century (and the publication of the Latin Gutenberg Bible) allowed for mass-production of printed materials, and formed the basis for future publication of Bibles. In 1526, William Tyndale, hot on the heels of the reforms in Europe led by Martin Luther, began the first-ever English language translation of the New Testament, known as the 'Worms New Testament', after the city in which it was begun. Tyndale, who was renowned for his acuity with languages, used the 1516 Erasmus translation of the Bible as his source, and over the course of some eighty years, developed what would become known as the King James Bible. This process was dramatised in David Edgar's 2011 play Written on the Heart at the Royal Shakespeare Company. The versions of the Bible Tyndale developed before the KJB were controversial and many were destroyed, but the die was cast for an English Bible. In 1535, Myles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter, published his own translation, the 'Coverdale Bible', the first complete version of the Bible in the English language, and was closely followed by a second mixed-language version by John Rogers.

At the command of Henry VIII, Thomas Cranmer (mentioned above in relation to the BCP), began what became known as the 'Great Bible', so named for its immense physical size. This made it only practicable for use in churches, but was widely distributed to all parishes, and were chained to the pulpit. Later, during the reign of Catholic Queen Mary I (Bloody Mary), exiled Protestants required a Bible for home use while away from their parishes. This resulted in a communally-developed Bible authored in Geneva, spearheaded by Coverdale and John Foxe, which was completed between 1557 and 1560, and was known as the Geneva Bible (or, somewhat irreverently due to an archaic translation, the "Breeches Bible"). The Geneva Bible pioneered the addition of verse numbers, allowing for easier reference. This became the predominant Bible used over the latter 16th century, and although there were updates to other texts (the Bishop's Bible of 1568 updated the Great Bible).

The Geneva Bible was revised nearly 150 times over the coming century, and was widely distributed. This would have been the Bible that Elizabeth I and Shakespeare both used, and the text of common reference for Shakespeare's early audiences.

Q: In what other kinds of documents would English-language excerpts from the Bible have been published? (Psalters, for example? The Elizabethan Homilies?)

A: Aside from the Geneva Bible and its competitors, The Books of Homilies were of greatest importance. These were published variously in 1547, 1562, and 1571, and were designed as a more in-depth and localised approach to Luther's Thirty-Nine Articles of religion, which initiated the reformation. Officially called Certain Sermons or Homilies Appointed to Be Read in Churches, these articles covered a closer reading of doctrine and often criticised the excesses of Catholicism. These were printed in vernacular English and were designed to be read aloud. A copy of these sermons, collected as The Elizabethan Homilies, is available here. Psalters (collections of Psalms along with the liturgy of the Saints and a liturgical calendar) were Catholic texts, so were no longer available by the late 16th century: in any case as expensively collated texts, were not designed for common consumption. We still have Psalters that belonged to the then-Catholic Henry VIII and Mary I.

Q: I have noticed that Richard Woodville is not in the list of Historical figures in the play. Any information would be great!

A: Biographical information on Richard Woodville (grandfather of Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, and Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV - all characters in Shakespeare's Henry VI Part Three and Richard III) is now available in the biography section here.

Q: I was just wondering about the change from 'Beauford' to 'Winchester' on page 12.

I know that the change was made to allow the audience to understand what character was being referenced.

I was wondering whether or not "Beauford" would be considered a pun. I know that much of this scene has Winchester and Gloucester using witty puns or words that seem to show the other in a worse light. Wouldn't "Beauford" be considered one of these? My reasoning behind this is the thought that using his real name is a pun in of itself. Throughout the scene Gloucester doesn't use any correct name or ways to reference Winchester. And by using Winchester's real name would Gloucester be trying to diss Winchester, and referencing his illegitimate birth in the words 'that regards nor God.' You and JRS have also been telling us that every time Shakespeare does something different that it is important. So wouldn't this first usage of "Beauford" be considered one of these important usages?

I understand that in the context of performance it makes sense to change it for the audience, but for the correctness of the play world would these ideas be right?

A: An excellent observation! This is a major concern when we talk about adapting texts from the Elizabethan period to the modern day, and considering what the audience hears and processes. We have to be aware of the playwright's (assumed) intention with placement of words, for sure, but if there is a danger of them disrupting the audience's experience by causing friction in their understanding, then we have the opportunity to smooth the way. Arguably, any pun made on 'Beaufort' would be more relevant to Shakespeare's audience, who would be aware that Beaufort is another way to refer to Winchester. But with a modern audience, who are already, by this point early in the play, burdened with nearly a dozen lordly names all based on geographical locations - Exeter, Bedford, Gloucester, York - there is a very real danger of assuming a name might cause confusion. If the 'Beaufort' reference was a major turning point or gave us a great deal of playable effect, then of course we would be less hasty to omit it, but in this case it can be considered not worth the distraction it causes. This is a very good question, however, and we encourage you to keep thinking in this way!

Q: Quick question: do you have any sense about the middle ages (Henry VI time) / Elizabethan (Shakespeare time) laws of bearing weaponry? Was it illegal to bear arms (sword, etc) at any place in London? Or could people openly carry? Did their status in society come into play?

A: With answers collated with thanks to our Fight Director, Daniel Levinson!

First, a very detailed article on the Right to Keep and Bear Arms

Then, a good overview of Elizabethan swordplay.

In Elizabethan times, many aspects of life were affected by a person's class, including weaponry. Unlike fashion, where there were actually laws separating the rich from poor, the difference in weapons was mainly because of monetary reasons (but it was not enforced by law). For example, the weapon of first choice in this period was the rapier, a long thin sword used mainly for thrusting, and so one way to determine the class or wealth of a man was by determining the quality of the sword. The poorest people, or the lower classes, were least likely to own a rapier, but it was imperative to carry some kind of weapon, so low class men would often carry cutting knives, daggers, or other forms of defense. Still, most of those in the middle class were expected to carry a rapier of some sort. Middle class civilians were unlikely to own one with a gilt, or gold hilt, but commonly had rapiers with iron-swept hilts. The weapons of greatest quality; however, were owned by the upper class, especially men of nobility, and their weapons were embellished with gilt, ivory handles, multiple fullers (or grooves down the blade), bone handles, and many other more elaborate pieces of weaponry.

Furthermore, all nobility and upperclassmen were expected to be fully trained in fencing, then known as defencing. At the age of five, males were given a small sword and began training. A rapier was expected to be present in all noble apparel, and it became a common custom for civilians in late fifteenth century Spain and then later spread into England.

Lastly were weapons of war. This section included, by far, the most diverse array of weaponry during this time period. Weapons such as, battle axes,basilards, maces, lances, arbalests, bills, billhooks, bows and arrows, caltrops, halberds, longbows, pikes, poleaxes, and spears were employed. Also, the development of firearms took place in this era. In fact, in 1595 all bows were ordered to be exchanged for muskets. Furthermore, cannons replaced other items of artillery, like the trebuchet, catapult, and ballista. Ultimately, the Elizabethan era included many many weapons, and weaponry developed greatly.

Source (unavailable)

Then, a useful 1566 bylaw governing weapon length:

Item, her majesty also ordereth and commandeth that no person shall wear any sword, rapier, or suchlike weapon that shall pass the length of one yard and half-a-quarter of the blade at the uttermost, nor any dagger above the length of 12 inches in blade at the most, nor any buckler with any point or pike above two inches in length. And if any cutler or other artifices shall sell, make, or keep in his house any sword, rapier, dagger, buckler, or suchlike contrary thereunto, the same to be imprisoned and to make fine at the Queen's majesty's pleasure, and the weapon to be forfeited; and if any such person shall offend a second time, then the same to be vanished from the place and town of his dwelling.

It is interesting that the term rapier is well known enough to be used in a royal proclamation published in 1566 in England. There is, still, some controversy about the origin of the word, and when and where it was used. The English Guild "Maisters of the Noble Science of Defence" were not teaching the rapier as a standard part of their cirriculum at this stage. Senior Rocco Bonneti would not arrive in London for another three years. Yet the term appears popular enough to appear unqualified in a royal proclamation.

The length of a sword was limited to "one yard and half-a-quarter of the blade". Without knowing specifically how this term was meant to be interpreted by Elizabeth's Magistrates and Officers, we can not be sure how long this is. The use of the word 'and' indicates that it was over one yard by something called 'half-a-quarter'. My interpretation is that it meant an additional half-a-quarter yard. This gives us a blade length of 1, 1/8 yards, or 40.5 Inches.

Daggers are limited to 12 inches in the blade. Which is still a considerably fearsome dagger. I would presume that this large length takes into account specialised knives and daggers used for special professions. A good cook's knife of the period approaches that length. Much bigger than this length gives the weapon the qualities of a seax (or falchion), a rather lethal weapon that authorities might not want people carrying around all the time.

Points on bucklers are apparently so common that they are regulated to a maximum length. The Wallace collection in London has some beautiful examples of such bucklers which have points of this or greater length. They generally seem to be a barbed pike head with a four-sided point. Such a point opens a nasty wound in the body, which does not naturally close again (similar to the French 3 sided bayonets of world war one). As recreators of the ancient art of Rapier fighting, we should be seriously looking at ways to allow buckler clashes and strikes.

The final parts are concerned with the enforcement of the proclamation items. Hosiers, being seen as pernicious offendors, are required to put up a bond in order to continue trading. In effect, I suspect, this became a matter of a fine before the event. Cutlers, Haberdashers, and Fencing Masters were not required to be bound in monies.

As has been noted by Turner and Soper, the length of a rapier was held to give definite advantage. There are cases cited of people seeking to purchase longer weapons before a duel in order to gain advantage over their opponent. It would seem that one effect of this proclamation would be to curb this activity (although I cannot see people organising duels for the middle of London city!). It could also be seen as a way of the monarch making a strong stand on matters that might be seen to be anti-English. Certainly when viewing this proclamation in concert with George Silver's comments in Paradoxes, I suggest that conservative members of early Elizabethan society would regard the shorter cut & thrust sword with favour, and the longer Tucks as "Un-English".

This proclamation appears to be the only one made by Elizabeth on weapons length.

Source (unavailable)

Now, a rundown on the kinds of weapons Elizabethan folk wielded:

The threat of the Spanish also ensured that many of the tried and tested weapons used during the Medieval period did not disappear. The following weapons were available during the Elizabethan era:

A variety of swords as well as the rapier including the Broadsword and the Cutting sword

- The Battle Axe - A variety single and double-handed axe were in use throughout the Medieval period

- The Mace - The mace was an armor-fighting weapon. The Mace developed from a steel ball on a wooden handle, to an elaborately spiked steel war club

- The Dagger including the Basilard, a two-edged, long bladed dagger

- The Lance - A long, strong, spear-like weapon. Designed for use on horseback

Weapons which could be used by Foot soldiers and Archers

- Arbalest - This is the correct term for a Crossbow

- Axe - Single and double-handed battle axes

- Basilard - A two-edged, long bladed dagger

- Bill - A polearm with a wide cutting blade occasionally with spikes and hooks

- Billhook - Capable of killing Knights and their horses

- Bow and Arrow

- Caltrop: Sharp spikes on 12 - 18 feet poles used, in formation, to maim a horse

- Crossbow - The crossbow range was 350 – 400 yards but could only be shot at a rate of 2 bolts per minute

- Dagger - A short pointed knife

- Halberd - A broad, short axe blade on a 6 foot pole with a spear point at the top with a back spike

- Longbow - The Longbow could pierce armour at ranges of more than 250 yards - a longbowman could release between 10 - 12 arrows per minute

- Mace - The mace was an armor-fighting weapon. The Mace developed from a steel ball on a wooden handle, to an elaborately spiked steel war club

- Pike - A long spear measuring between 18 feet and 20 feet

- Poleaxe - Polearm - Polehammer - Bec de Corbin - Bec de Faucon - A group of pole-mounted weapons. Were all variations of poles measuring 6 feet long with different 'heads' - spikes, hammers, axe

- Spear - Used for thrusting

- Elizabethan Weapons - Firearms

By the end of the 1500's firearms were in common use. The musket was invented towards the end of the Medieval era in 1520. By 1595 all bows were ordered to be exchanged for muskets. The most popular firearm was called a Matchlock (this name derived as it was fired by the application of a burning match). It was inaccurate, slow to load and expensive. It was eventually replaced by the Flintlock. Canons were developed which replaced the heavy artillery of the Medieval years such as the ballista, trebuchet and the Mangonel. These early canons were made of bronze or iron and fired stone or iron. They were made in different sizes and were used on both land and on sea.

Q: I was just wondering whether or not were sure that the Countess of Auvergne is a fictional character.

There are two entries on wikipedia that reference the Countess’ of Auvergne.

Both which lived after Henry V’s death.

I am wondering this because I wonder if the scene is actually important. I know that some scholars believe that it is an unimportant scene, but considering the text, where it occurs in it and what happens in the scene, could this scene simply represent a joke, that Shakespeare put in to make fun of the French? It might even be there to keep the joke going from the other scene of the drunken French, from 2.1.

For example, it could have been a common legend that, the Countess tried to capture Talbot and Talbot didn’t even need to try and not get captured. Or that the Countess was known as being stupid or simple minded, trying to get Talbot but so easily failed.

This is just a thought, I don’t know what else can support this.

A: When I suggested that the character of the Countess was fictional, that was of course not to suggest that the title and the position did not exist. As you've suggested, there were a couple of Countesses in the appropriate time frame. Joan II died before the time period we're talking about, so it's more likely to be Marie I, but remember that in the period immediately following the Siege of Orleans, Talbot was imprisoned for four years, so historical timelines are not to be trusted. Marie I died some three years after Talbot was released, so that would be the timeframe the meeting would happen in, but the main reason why the Countess is considered to be fictional is that we have no evidence that such a meeting ever happened.

James Riddell's article (pdf) on the meeting gives us plenty of material on the scene, and poses some theories about what it means.

Q: Do you have some kind of visual aid / chart to show how characters in the play are related by family (blood), friendship, and loyalty?

A: To start with, here are charts relating to the Yorks and Lancasters, which is entirely built by blood relation.

In terms of loyalty, the factions in the play are as follows:

YORKISTS

York

Warwick

Vernon

Mortimer

THE KING'S SIDE

Henry VI

Gloucester

Winchester

Talbot

Bedford

Salisbury

Burgundy (in part)

Woodville

LANCASTRIANS

Somerset

Suffolk

Basset

FRENCH

Dauphin

Bastard

Reignier

Joan

Margaret

Burgundy (in part)

Q: What is a 'Sick Chair'? Would it be carried or on wheels?

A: This question is addressed with the Shakespeare and the Queen's Men project, when they had to use a 'Sick Chair' for The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth. They initially thought of using a litter (like we discussed) but found it impracticable, whereas a chair on wheels was feasible for the period. Check out the entire post on the subject here. The wheelchair/sick chair that Alec Guinness used in the 1953 Stratford production that I was talking about is depicted in this article.

Q: I’m having trouble finding any references to how lightning would have been created on stage during the 1600’s. I have ideas on how to do it with stage lights but I don’t know that JRS will want that kind of look. I’ve had no luck with the books she has given me for reference (Theatre of Fire and Early Modern Theatre) and my searches online aren’t turning up anything either. Any suggestions?

Arden Shakespeare published an excellent book in 2013 called Shakespeare's Theatres and the Effects of Performance, which is available at the Porter library here. In that volume, Gwilym Jones has a chapter called "Storm Effects in Shakespeare," in which he suggests, amongst other things, that lightning was effected with pyrotechnics and fireworks. I would start with this article: you could also use reflectors to redirect light, or rely on the thunder sound effect to intimate lightning. There's nothing to suggest it should be forked lightning, so a sudden flash from a reflector sheet might do it. If you can't find the Arden book let me know and I can bring my copy in.

Q: How does the Earl of Shrewsbury rank with Suffolk, York, Gloucester, and Somerset?

The hereditary title of the Earl of Shrewsbury was dormant for about 300 years before it was revived for Talbot. The first Earl was an advisor to William the Conqueror, but the rank was left forfeit after the First Earl's descendant joined a rebellion against Henry I. When Talbot was given the title, he did not earn it by birth, obviously, and he is not of royal blood. No one disputes his heroism, but there might be a hint of 'new money' to his rank - as in, it's not as 'real' to the older families.

And a follow-up...

Q: I’m wondering about how the onstage characters, York, Somerset, and Talbot/Shrewsbury would read Talbot’s new relative rank, in order to sort out the order they should appear in Henry’s coronation procession. Do you think there would be a “correct” place for him, or could I build a bit of business in which the peers do a bit of jockeying?

Well, I think that York and Somerset are both ‘old money’ in terms of their heritage but they are both young men - Somerset is called ‘young Somerset’ in the roses scene - so their sense of self is likely inflated. York makes it clear that he is forced to play a low-key role as he bides his time, so he is unlikely to be too aggressive, but overall I think it would make a lot of sense if there was a bit of jockeying business over the fact that Talbot is ‘new money’ yet is far more accomplished than either Somerset or York in battle. I think they’re kind of terrified by Talbot physically but grumble under their breaths about his right to be elevated.

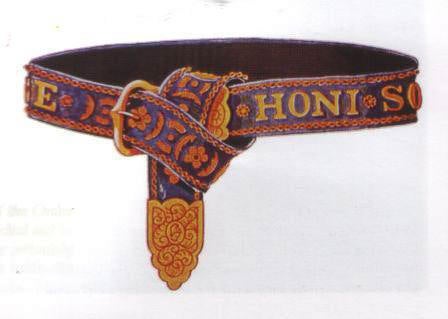

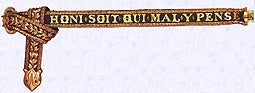

Q: When Talbot confronts Falstaff for his cowardice, he vows "To teare the Garter from thy Crauens legge". What would the Order of the Garter look like?

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is a high-level, prestigious honorific awarded for high levels of chivalry. It was founded in the fourteenth century and still exists today. Knights of the Garter wear a blue ceremonial carter with gold lettering which spells out Honi soit qui mal y pense, a Middle French motto which roughly translates to "shame on him who thinks this evil."

And a follow-up on the Garter...

Q: Which leg would the order of the garter be worn on? The right one?

According to the website of the Queen's Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard, the garter is tied around the left leg just below the knee, as demonstrated below.

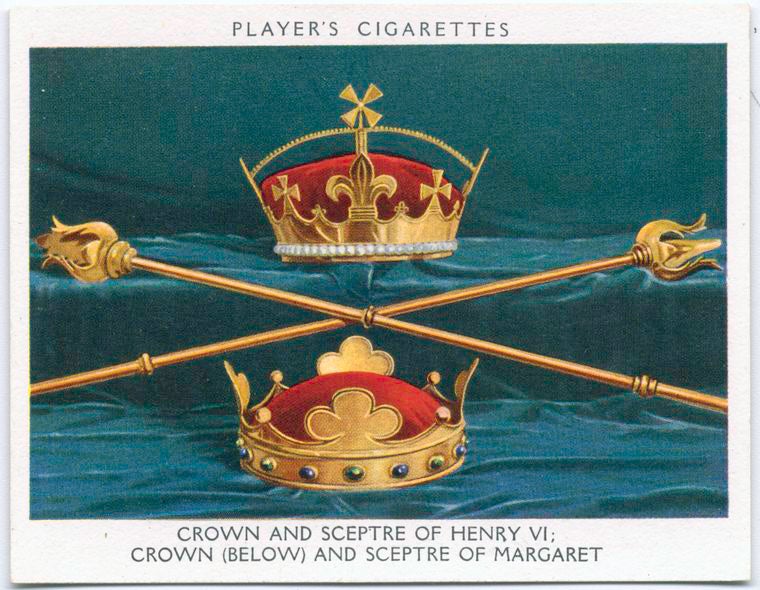

Q: What kind of crown would Henry VI have worn? Would it have been like the crown jewels in the Tower of London?

The crown jewels in the Tower of London are a ceremonial set of coronation jewels, and the most iconic version we think of today are less than a century old, remade in the mid twentieth century.

Here is an image of the crown that Henry VI wore on ceremonial occasions. He would likely have worn a smaller coronet when in battle settings.

Q: I Need a sense of the size and colour of the Dauphin’s circlet that he would wear? I have an idea but it might be totally wrong.

I have found a few images of the Dauphin's coronation at Rheims and depictions of him at court, which seems to suggest a fairly modest gold/silver crown.

Q: Our pall bearers are going to wear a strip of fabric tied around their upper arm as a symbol of mourning. Which arm do you think it would be worn on?

Traditionally, a black mourning armband would be worn on the left arm, which is the side closest to the heart as a sign of respect to the dead.

Q: I have a quick question about sounds and stage directions.

Senet is one of the stage directions that appears in the play. What exactly is a senet?

A 'sennet' is an Elizabethan term for a trumpet announcement which tells us that a king or queen are about to enter. It may be as simple as a couple of notes: 'bum bum baaaa', or could be very intricate, like in the below video.