Roots and tributaries

Call me Simon, and say it politely. It's not a bad name for a troll, really. I got it from the Mennonite folks who farmed this land, east of Laurel Creek and north of the village of Waterloo, for rather more than a century before there was such a thing as a university here. Before that, the Neutral Indians who occupied the forests hereabouts had a longer name for me, and less easily pronounced, even for those who have no trouble getting their tongues around Brzustowski, Kalbfleisch, Chandrashekar, Schwartzentruber and Ng. Yes, call me Simon, or simon@uwaterloo.ca now that I'm wired like the rest of the university; and listen for a while. You might be surprised how much you can learn from a troll about the history of your own university.

After all, I've been here for a long time and I've seen a lot of water pass under the bridge. I speak in particular of the bridge over Laurel Creek beside the Health Services pond, where I now live in all the squalor trolls traditionally enjoy, but I've been on this land since before there was either a pond or a bridge. I've seen a lot and read a lot, and of course I've heard a good deal from other trolls over the years. It was a colleague who lives near your village of St. Agatha, a few miles out Erb Street, who gave me the earliest news of what would turn out to be a predecessor of your university. Just one predecessor; there are several early foundations, widely separated, on which your university was built, just as Laurel Creek is made out of the tricklings of Clair Creek, Maple Hill Creek and other tributaries up in those hills and subdivisions north and west of the campus.

That first news came in the human year 1865. I heard from St. Agatha, as I say, that a Roman Catholic priest from Germany had started a college - in a log cabin, of all the foolish things - and named it after St. Jerome, one of the great scholars of the early Christian church. There's a picture of the old saint hanging now in the modern St. Jerome's College building, although I can't quite believe it's a good likeness; it's a copy of a painting by El Greco, who made all his subjects grotesquely tall and thin. He could have used some help from the college of optometry, but it wasn't started until 1925, as I'm going to mention in a few moments.

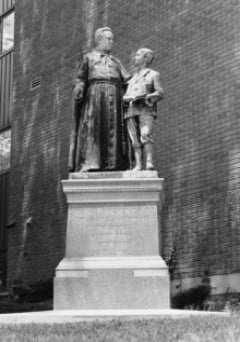

As I was saying: this priest, whose name was Louis Funcken, started a college, with seven young men for his students. Now that's a student-teacher ratio for the modern university to envy! It wasn't always that way, though; a few years later, when Father Funcken had moved his college from St. Agatha to Kitchener, he found himself not only teaching all the students, a good deal more than seven by then, but also working full-time as the rector of St. Mary's Church. He seems to have been equally good at all his duties, and was loved almost as much as he was respected. No doubt that's why the college's first building in Kitchener was named Louis Hall, and why a bronze statue of him was erected at the St. Jerome's site downtown, making him, so far as I know, the only founder of this university, however remote, to have received such an honour. I wonder why St. Jerome's doesn't have that statue moved up to its quadrangle in Waterloo one of these days.

I'll tell you more later about St. Jerome's and how it flourished after the death of Father Funcken in 1890, but let me move on to say a word about another religious group in Kitchener-Waterloo that decided it needed a college. (Humans! One faith, and thirty competing churches!) That would be the Lutherans - you'll notice there was no action, for several decades more, from the Mennonites who actually lived on these farms beside the creek. The Lutherans were almost as keen as the Roman Catholics to create a seminary, a college to train members of the clergy, and their "evangelical" seminary was founded in 1911 on the outskirts of Waterloo, a short walk up Albert Street from Silver Lake and the beautiful park that was the centre of the little town's life in those days. (Don't let me get distracted, please, into talking about the experiences of the trolls who have lived in that park over the years, watching Professor Thiele's band concerts on summer evenings, or competing with the filthy ducks for quiet enjoyment of the lake.)

As I was saying, that was in 1911. Interestingly, two other things happened some distance away but within a few years of that founding that would play a huge and unexpected role in the beginnings of your university. (Don't ask how I know. If there's one thing trolls have time to do, it's read, and if there's one thing trolls like to read, chuckling at the absurdities of human ambition, it's the time-yellowed contents of archives.) What, I hope you are asking, were these two other events? One was a birth, in Hamilton in 1904, of a boy who grew up under the name of Joseph Gerald Hagey, a boy who became a man with a fast handshake and a penchant for thinking big. The other was even farther away from Waterloo than that, for it happened in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1906, the University of Cincinnati introduced what it called a "co-operative" program for its engineering school, by which students would move back and forth every few months between the classroom and paying jobs where they'd learn the practical side of their profession. Such an idea had never been tried anywhere in North America. As you'll immediately recognize, it would catch on in Waterloo half a century later.

Then two things of interest happened in 1925. Very much like St. Jerome's, the Lutheran establishment had extended its range beyond theology, to include general undergraduate studies in the arts. (Unlike St. Jerome's, though, it didn't add a high school division, sticking to work at the undergraduate level.) It soon had a new name, Waterloo College, and to guarantee academic respectability it affiliated itself in 1925 to the University of Western Ontario. In the same year came the founding of the College of Optometry of Ontario. Not part of any university, although it was on the fringes of the University of Toronto, it was in effect a trade school for members of a new and not well understood profession: "eye doctors" who would be not physicians but scientists, experts in how the human eye actually worked and how its optics might be improved with lenses. As you know, I'm sure, the College of Optometry is no more, for it was reborn in 1967 as the school of optometry of your university, and in 1974 it moved into a building on what I still prefer to think of as the Brubacher farm. But I'm getting ahead of the story, which is so easy to do with a place like Waterloo where events move fast.

Let me review the situation. By the early 1950s, there was Waterloo College in Waterloo. There was St. Jerome's College in Kitchener, with a high school site downtown and a college site in preparation at "Kingsdale" out at the fringe of the city, and now affiliated to the University of Ottawa just as Waterloo College was affiliated to Western. There was the College of Optometry in Toronto. There was J. G. Hagey cresting a successful career in public relations for B. F. Goodrich Canada. There was the faraway University of Cincinnati sending engineering students out regularly to work in industry. And here on the banks of Laurel Creek, there were some seven farms, all established for a century or so by Mennonite families who had come to the area about 1820. That was right after the Napoleonic wars, which of course explains why Waterloo is named for a battle and both Wellington County and the village of Wellesley are named for the general who won it; but that's a whole other story which I'll leave to other tellers. Seven farms, as I say, including the Brubachers with their stone house on a knoll up to the north of here, and the Schweitzers in their less impressive stucco house just off Dearborn Street. Their home, you know, has been reborn and expanded as the Graduate House, and their orchard still bears little apples in the early fall on the hill overlooking the Dana Porter Library.

In 1953, the same year when St. Jerome's opened its new Kingsdale campus, a big step was taken. The movers and shakers of Waterloo College, as I heard at the time from my troll friends down in that neighbourhood, prevailed on Gerry Hagey, the business whiz who'd never worked a day in any institution of learning, to become president of Waterloo College, leading it away from a church orientation and a little way into the modern world. He accepted, and immediately found, as college presidents always find, that the big problem is money and where to get more of it. "Hagey was convinced," your historian James Scott wrote later, "that the only way Waterloo College could expand would be with the help of government money." Needless to say, the expansion would also involve new programs in fields like science and engineering, which were a lot more popular in 1954 than they had been in 1865. (Humans are slow learners, but they do learn eventually.) Hagey called a few of his business friends to chat with him at the Granite Club one day in the fall of 1955, and there was a more formal meeting on December 16 that year, which led to a provisional board of governors for "a faculty of science to be affiliated with Waterloo College". I've seen a list of the business people, publishers and physicians who were at that meeting; interestingly, there are no women on the list, and perhaps it won't surprise you to hear that the two trolls who were present also aren't mentioned on the list. I name no names, but I could tell you a story or two about cigars.

Anyway, by April 1956 the project was called Waterloo College Associate Faculties, by June the Evangelical Lutheran Synod had given its okay, and in the fall Hagey and his colleagues were trying to decide exactly what they were going to teach. "The entire resources for teaching science at Waterloo College," Scott has plaintively written, "consisted of two faculty members - Bruce W. Kelley, Chemistry, and H. K. Ellenton in Physics - and a single laboratory which when it was inventoried later was worth approximately $19,000." Not counting any value it might have had as a historic site, I suppose.

I'm sure you know what they originally wanted to introduce, here by the creeks and orchards: a six-year program that would include grade 13 and five subsequent years of technical education. Students would be able to graduate with either an engineering degree or a technician's certificate, after studying everything from mathematics and economics to technical drawing and electronics. Oh, and "semantics". Scott says he doesn't know what that subject was supposed to include, but I could enlighten him, if he only asked. "Semantics" is the skill of explaining the correct technical solution of a problem to a client who doesn't understand the problem, but doesn't know that he doesn't know.

By August 1956, Hagey was introducing the idea of co- operative education to his new board of governors. Some time that winter, the idea of a technical program below the university level was dropped from the new faculty's offerings. As the year came to an end, people from Waterloo were visiting Cincinnati (and other co-op universities, such as Antioch College) to see what they might learn. And they were preparing a curriculum plan to submit to the authorities at Western, with which their parent, Waterloo College, was still associated.

They probably knew, by the last day of 1956, that a new university was being born. But nobody had said so yet. Drop by again after Christmas, if you like, and I'll tell you what happened in the new year, 1957. Don't drop by during the Christmas season, though, if you don't mind. Trolls don't celebrate much, and I wouldn't want you to get the idea that I'm grumpy, or anything like that.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1865-1956: Roots and tributaries

- 1957: The first long hot summer

- 1958: The campus comes to the creek

- 1959: Then there was science

- 1960: And next there was arts

- 1961: Growth and complexity

- 1962: Expansion by degrees

- 1963: Facing the baby boom

- 1964: Into the computer era

- 1965: A library at the centre

- 1966: Times a-changin'

- 1967: The giant celebrates

- 1968: End of the old regime

- 1969: Year of struggle

- 1970: The second president

- 1971: Structure and sculpture

- 1972: The Act and the moratorium

- 1973: Inflation and job markets

- 1974: Tale of two parades

- 1975: Sad times, hard times

- 1976: Year of long meetings

- 1977: UW doesn't win the lottery

- 1978: When the dollar dropped

- 1979: Facing the third decade

- 1980: A pie in the face

- 1981: Return of the engineer

- 1982: The busiest year

- 1983: Waking up to change

- 1984: The megaprojects

- 1985: Yuppies and biotechnology

- 1986: The dreadful plight

- 1987: Beyond the Villages

- 1988: A revolting year

- 1989: The writing of policies

- 1990: Lies and frustrations

- 1991: A cunning plan

- 1992: We have to press on

- 1993: The end of history