Year of long meetings

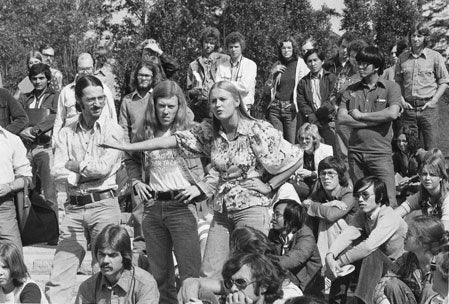

Phyllis Burke of the Federation of Students staff speaks to a “freedom of the press rally” in October, charging that “it has been the policy of the Anti-Imperialist Alliance to infiltrate The Chevron”.

Long meetings were a prominent feature of life at Waterloo in 1976, some of them prolonged -- or instigated -- by what were then called "radicals", and others of them probably inevitable in a consultative place like a university. In the second category comes the senate meeting of February 16, 1976, which was held in the Theatre of the Arts and lasted until half-past midnight. I suppose you want to know all the details, or you wouldn't have sought me out here under the bridge, now would you?

Well, that meeting was long (and hot, and cranky, and for the most part pretty boring) because the chief item on the agenda was what should be done about the department of human relations and counselling studies. I suppose most people now at Waterloo have never so much as heard of HRCS, but believe me, everybody had heard of it in 1975 and 1976, particularly after a review committee reported to the senate that "the most striking feature of the undergraduate program is the lack of any structure", the PhD program was "on very weak ground", and the faculty members were afflicted by "bitter and personal divisions". In short, the little department was a mess. Its six faculty members, shocked into unanimity, presented a brief that said they were willing to try to rebuild, if the university would help with more people and more money. "We do not believe," countered the dean of graduate studies in a stunning display of numeracy, "that any useful purpose would be served by giving this department a second chance for the third time." If I am not mistaken, that was also the meeting that was enlivened by a speech from Marsha Forest, one of the six, comparing her qualifications and career prospects to those of the department's chair, Arthur Wiener: "We are both short; we are both Jewish; we both wear glasses." Towards midnight, anyway, the senate voted on closing HRCS: 34 in favour, eight against.

Most of the audience melted away, and the theatre looked empty with only about forty spectators left. They were the irate, if weary, students from the department of recreation who had come to protest a plan to move their department off campus. It had been squeezed into corners in the Math and Computer building, which everybody recognized was no longer adequate, but there was no prospect of a new building for rec and kinesiology in the foreseeable future, and the Administration had decided they'd have to move off campus. The university struck a deal with a land developer to put up a no-name building at 415 Phillip Street, next door to 419, which UW was already renting, and move recreation there along with a few other occupants. The students lamented the likely loss of academic contact, not to mention the long cold winter walks, and one faculty representative on senate called it "criminal" to move an academic department off campus -- perhaps forgetting the precedents. Architecture was at 419 Phillip already, and psychology had been at the corner of Phillip and Columbia until a couple of years previously. However, there was no real alternative, and senate voted against registering its opposition to the plan. As things worked out once the concrete blocks were all in place, recreation eventually moved into 415 Phillip, not 419, and architecture got 419; at least I think that's right. Among the other UW units to get a slice of the new rental space was the library, which moved for the first time to put books into storage, some 30,000 volumes that year.

So that was one of the year's most memorable meetings. Another was a Federation of Students general meeting held in the main gym of the Physical Activities Complex; another was a mass meeting in the arts quadrangle, although what it was a meeting of might be a matter of opinion. Then there were the very long meetings held by the selection committee for your university's very first Distinguished Teacher Awards, which naturally were not open to human visitors but which found it quite impossible to exclude trolls. The awards were the brainchild of Tom Brzustowski, the vice-president (academic), who put huge emphasis on undergraduate teaching. Including his own, I might add: vice-presidents have tight schedules, and it wasn't always easy for a dean to get in to see TAB, but he could invariably find time to see one of his undergraduate students who needed advice about a term project in combustion. Anyway, the first three teaching awards were presented that spring, with considerable hoopla, to Horst Leipholz, David Davies and John Wainwright.

Later in the year came another step towards acknowledging the importance of teaching. The university advertised the position of "teaching resource officer", got more than 60 applications for the job, and eventually chose Christopher Knapper, an Englishman via the University of Regina, who set up shop at Waterloo, started assembling a library of books and other materials to help people improve their teaching, and made some uncomplimentary remarks about the state of high-tech Waterloo's telephone switchboard compared with, say, the one at Regina. Yet another teaching development hit the national headlines in September: the first English Language Proficiency Examination, written by entering students in arts. It was announced at a news conference that 44 per cent of those who had written the exam "needed help" and would get it at a new "writing centre" headed by one of the more colourful figures in the faculty of arts, the hillbilly-in-a-caftan who was associate dean, Ken Ledbetter.

Other academic innovations that year? Well, a co-op program was introduced in the English department -- seems to me Ledbetter was behind that new departure as well. The faculty of engineering acquired the Sandford Fleming Foundation, which would sponsor scholarships, debates and other programs to promote the quality of engineering education. Final approval was given for the creation of a department of religious studies, just thirteen days before the closing of HRCS was sealed (and that drew a few snide remarks from the devoutly secular, I can tell you). The accounting program, which wasn't yet a "school", started a new stream to train Registered Industrial Accountants. And the department of management sciences announced a minor for undergraduates; until then it had taught strictly at the graduate level.

Among the newcomers to campus was Don Ranney, a former orthopedic surgeon. Some people may have thought he was the only medical doctor on campus; he wasn't, as there was one in the statistics department too, but he was one who had come with an unusual gleam in his eye. Within two years he had done what he came to do: established a "school of anatomy", authorized by law as a place where human bodies could be dissected. Optometry and kinesiology students would both benefit -- and sometimes walk out feeling more than a little solemn -- from the unique experience of seeing, really seeing, what the muscles of the eye or the hand are like.

Trolls were sceptical when it was announced that the Brubacher House on the north campus would be renovated and turned into a museum. The place had been a ruin since a fire ten years earlier, and most of us were just as happy to see it left alone as a gentle and unpopulated reminder of the days before a university was built on the German Company Tract. More than a hundred years old, the house was (and still is) one of the few links to the days of Mennonite cornfields, if you will allow the possibility that a cornfield can be Mennonite. However, I have to say that the delicacy of that renovation, and the taste with which it presents nineteenth century Waterloo County to twentieth century visitors, are by no means the worst thing that has ever happened here along Laurel Creek.

If the prospect of a renovation was a human threat to trollian culture, though, we had plenty of opportunity to laugh at human beings. That was the year the Parti Quebecois was elected for the first time ("Everybody take a Valium," said Rene Levesque in a famous cartoon). The so-called "energy crisis" was well under way, and in May 1976 the campus suffered its first "brownout" as Ontario Hydro cut the voltage for an hour or two in the face of demand higher than it could meet. There were dire predictions of damage to computers, most of which didn't come true. And while energy was scarce, so was money, especially in staff members' pockets after the federal Anti-Inflation Board rolled back a double-digit pay increase they had been told to expect. The people in the housing office, meanwhile, supported the forest product industry by generating a total of 71,600 sheets of paper, as required by the provincial government, to support its application for approval of an increase in residence fees. Later, the government would stop insisting that institutional residences go through those motions.

The Athena swimming team won a national championship, one of the few your university has ever collected. The library introduced the Waterloo Machine-Assisted Reference Service, or Watmars, which offered professional help in searching the few cumbersome electronic databases that had been introduced; the World Wide Web was a long, long time in the future. The director of security responded to the usual rumours of sexual assaults in an unusually direct way: "There haven't been any rapes on campus," he said publicly. Plans for a Federation of Students anti-rape patrol were shelved. Librarians at UW got a new job structure, allowing them to move from Librarian I through the ranks to Librarian V, something like the progress that faculty members make from assistant professor to associate to full professor. The faculty association said it welcomed librarians as members, and a few of them joined. (The faculty association also received a report, not for the first time and not for the last, which concluded that there was no point in its pursuing union certification.)

Now I've saved the best for last in telling you about the events of 1976. Or if it's not the best, at least it's the most exciting, for those who like sound and fury. I refer to the "Chevron affair", to which we owe the inestimable boon of having the present student newspaper on this campus. Yes, of course I read Imprint, whenever a stray sheet of it blows over from Mrs. Brown's (sorry, I still call the St. Jerome's coffee shop by its ancient name) and gets caught on the palings of my bridge here. Before Imprint I used to read The Chevron, and before The Chevron I used to read The Coryphaeus, which I'll bet you have never so much as heard of. It was started, at least in newspaper form, by a fellow called Sid Black, a Ryerson graduate who turned up here and found himself a lot more interested in journalism than in his ostensible studies. When he left Waterloo he went on to be president of Canadian University Press, a nationwide organization for student newspapers, and he left Waterloo with a lively, not to say muck-raking, newspaper. The change of name to The Chevron was not without controversy of its own, but it was ancient history before 1976 -- in fact, as I think I've mentioned to you before now, the paper had gone through some glory days around 1970 as a real force on campus.

It was much less of a force by 1976, but it certainly attracted attention that year with more and more references to something known as Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Tse-Tung-Thought, which was the philosophy, or "line", of the Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist) and its local avatar, the Anti-Imperialist Alliance. The AIA had emerged from the Renison controversies of the previous couple of years, and with remarkable political acumen it latched onto one cause after another, attracting followers in spite of the length of its meetings and the even more revolting length of its slogans ("Hail the Emerging Friendship Between the Workers, Farmers and Fishermen of Canada and the People's Republic of China"). A few AIA folks with talent and time joined the Chevron staff, the most prominent of them being a charismatic young blond Scot named Neil Docherty, who became the newspaper's production manager. With a simple willingness to outlast everybody else at meetings -- they'd just keep talking until the ordinary folks were exhausted, or bored out of their minds, and went home -- they gained a good deal of influence over the newspaper.

In September its editor, Adrian Rodway, got tired of the situation and resigned, making sure that the leaders of the Federation of Students knew exactly why. They promptly announced that the Chevron was being closed for four weeks, something they had the authority to do in those days, and the fight was on. Within hours the Chevron staff (at least that was who they said they were) were "occupying" the newspaper offices in the lower level of the Campus Centre. Within two weeks they were publishing The Free Chevron. Within a couple more weeks after that, Fed folks and some people who said they favoured "objective" journalism were retaliating with The Real Chevron, which had a lot less panache but also a lot less rhetoric.

That would be about the point at which that mass meeting in the arts quadrangle took place; one of its highlights came when Doug Wahlsten, a psychology professor (rat expert, actually) who was a central figure in the AIA denounced everybody in sight for shutting down The Chevron, and was greeted with a hail of abuse and confetti from engineers who had come out to make sure the radicals were humiliated. The sequence of arguments, subpoenas, broken windows, changed locks, counter-charges and referendums which followed was too much for me to follow at the time, let alone remember two decades later. But I do know that while The Free Chevron lingered for months, eventually bringing the CPC(M-L) line to campus from an office somewhere downtown, the publications budget and the offices in the Campus Centre were eventually turned over to a newly created student newspaper: Imprint.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1865-1956: Roots and tributaries

- 1957: The first long hot summer

- 1958: The campus comes to the creek

- 1959: Then there was science

- 1960: And next there was arts

- 1961: Growth and complexity

- 1962: Expansion by degrees

- 1963: Facing the baby boom

- 1964: Into the computer era

- 1965: A library at the centre

- 1966: Times a-changin'

- 1967: The giant celebrates

- 1968: End of the old regime

- 1969: Year of struggle

- 1970: The second president

- 1971: Structure and sculpture

- 1972: The Act and the moratorium

- 1973: Inflation and job markets

- 1974: Tale of two parades

- 1975: Sad times, hard times

- 1976: Year of long meetings

- 1977: UW doesn't win the lottery

- 1978: When the dollar dropped

- 1979: Facing the third decade

- 1980: A pie in the face

- 1981: Return of the engineer

- 1982: The busiest year

- 1983: Waking up to change

- 1984: The megaprojects

- 1985: Yuppies and biotechnology

- 1986: The dreadful plight

- 1987: Beyond the Villages

- 1988: A revolting year

- 1989: The writing of policies

- 1990: Lies and frustrations

- 1991: A cunning plan

- 1992: We have to press on

- 1993: The end of history