An introduction to university writing

You have graduated from high school and been accepted to The University of Waterloo. Congratulations! As you begin your university studies you will encounter many kinds of writing assignments. To help get you started, here’s a brief guide to expectations for university-level writing.

Writing at university follows specific conventions

Whether you’re writing a blog post, text message, or lab report, written communication is based on four main elements: the writer (that’s you!); the reader; the topic, subject matter, or purpose; and the text. In order to communicate effectively, you need to suit your writing to your particular purpose and audience.

Image source: The Writing Triangle

The language, style and format of a text message to your best friend are very different from the language, style and format you would use in an essay you write for a professor, but in both cases, you should write using the conventions of the form that are appropriate to your purpose and audience.

An excerpt from our learning resource on word choice explains:

Reading and writing are usually not solitary activities. Think of written communication as a process with multiple players; often, at the most basic level, there exists a writer, a message to be conveyed, and an audience of one or more readers. Your job as a writer is to ensure that you consider your audience’s needs when writing, including word choice and organization.

Neglecting this aspect of your writing may mean that the message is lost or misinterpreted.

Here are some important questions to ask yourself about your audience that may direct the stylistic choices you make in your writing:

- What is my audience’s level of knowledge about my subject?

- Is my audience comprised of experts in the field?

- Am I trying to persuade my audience of something, or am I merely conveying factual information?

For examples and helpful advice about the components and conventions of several types of university-level writing tasks, such as lab reports, case studies, and reflective writing, check out writeonline.ca

What’s my purpose? Understanding assignment instructions

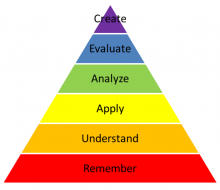

Understanding the purpose of the assignment is the first step in succeeding at any university-level writing task. Scan the assignment instructions for clues about what the assignment is asking you to do. Look for key words like “discuss,” “analyze,” “evaluate,” and “compare.” Most assignments will ask you to demonstrate higher order thinking skills. When we learn, our knowledge moves from lower-order, or less complex cognitive processes like remembering and understanding, to higher-order, or more complex ones like analyzing and evaluating.

Image source: An Introduction to Bloom’s Taxonomy

In high school, you might have had to memorize part of the periodic table of the elements. In a university course, you might be required to design a solution to a real-world challenge, such as recovering the gold dust from floor-sweepings collected from a jewellery manufacturer’s factory. Instead of being asked to summarize a book or article to demonstrate that you understand it, in a university-level course you might instead be asked to evaluate it by assessing the strengths and weaknesses of its claims, or analyze it by explaining how it is put together (for example, what kinds of organizational strategy or words does the author use?; does the text use logic or emotion to convince readers?; what are the effects of the text’s components?). You should become familiar with common assignment terminology in order to ensure your work meets the expectations and requirements of an assignment.

The writing process as learning process

While some high school students manage to write essays the night before they are due and still earn grades they are happy with, university-level writing assignments are longer and more complex, requiring more thought and development. It becomes more and more important to learn to treat writing as a multi-step process, and to give yourself time to complete each step.

There are six main stages your writing process might include:

- Understanding the assignment

- Locating, evaluating, and reading research sources (talk to someone at one of the campus libraries if you need help with this step)

- Crafting a tentative thesis statement and developing an outline of your arguments

- Writing a rough draft

- Revising the rough draft extensively

- Editing and proofreading for spelling and mechanics (you can find helpful resources under the "mechanics" tab)

Three myths about university writing

Myth 1: an essay must have five paragraphs

The five-paragraph essay model served a valid purpose in elementary and secondary school, but does not apply to university-level essay assignments. An academic essay should include an introduction, conclusion, and body, but you don’t need to worry about limiting your body to only three paragraphs. A complete, unified paragraph expresses a single idea or argument. The number of paragraphs you need to use in an assignment will depend on the length of the assignment and the number of arguments you want to make.

Myth 2: a thesis is just my opinion

A thesis is more than an opinion. Universities are places where scholars conduct research to create knowledge; we are constantly trying to refine what we know about the world and the way it works. In order to do achieve these goals, scholars need to be familiar with what information is already available, and acknowledge that their new ideas build upon what previous experts have already discovered. This is why your professors require that you cite your sources to avoid plagiarism. As a university student, you are now a scholar-in-training. The arguments you make should draw from the studies that other scholars have already published, not just your opinions. You need to acknowledge how these scholars helped you to understand your topic and develop your argument.

Myth 3: writing needs to include big words and long sentences in order to sound academic

Readers, even your professors, value clear, concise writing. To make your writing stronger, try replacing verbs like “to be” or “to have” with more precise, active verbs:

Weak: Ice cream enthusiasts Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield were the founders of “Ben & Jerry’s” in 1978.

Stronger: Ice cream enthusiasts Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield founded “Ben & Jerry’s” in 1978.

Weak: I was the manager of a “Ben & Jerry’s” store for six years.

Stronger: I managed a “Ben & Jerry’s” store for six years.

See our learning resources on Writing Concisely and Revision for more tips.

Works Cited

Forbes, Sarah. Bloom’s Taxonomy. The University of Waterloo Centre for Teaching Excellence, 2015. Web. 31 Aug. 2016. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/planning-courses-and-assignments/course-design/blooms-taxonomy

Silber, Anderson. “Some General Advice on Academic Essay-Writing.” University of Toronto Writing, 1995. Web. 5 Aug. 2015. http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/general/general-advice

Terms Frequently Used in Writing Assignments. Queen’s University Writing Centre. 2013. Web. Aug. 2015.

“The Writing Triangle.” Writing@CSU. The Writing Studio at Colorado State University. Web. 5 Aug. 2015. http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/commenting/triangle.cfm