Writing in English is hard. I know because I’ve been doing so every day for the last ten years. Navigating a labyrinth of sudden structural differences and changing expectations, my path towards writing my Master’s and PhD theses was not an easy one. I was ill-prepared for English writing, despite studying the language for twelve years in school and speaking it fluently. On top of that, since the COVID-19 pandemic has completely altered our routines and ways of life, many grad students struggle even more to focus on writing while they are far away from their families, friends, and loved ones. These are trying times!

So, if English is not your first language—like in my case—here I offer some suggestions strategies and techniques that have helped me complete a dissertation in my second language. These strategies revolve around what I consider the two most important elements to producing graduate-level papers: planning and organization.

Why planning and organizing?

First thing’s first: why do I emphasize planning and organizing? Isn’t that what all graduate students are supposed to do before writing anyway? In short: yes, it is. But there is a reason why planning and organization are extra important for EAL grad students.

Processing information in an additional language presents an extra challenge: English might have different linguistic structure than your first language. For example, academic writing in Spanish has

- a heavy focus on theoretical background information, sometimes over the author’s own thesis;

- arguments that are often located towards the end rather than stated in the beginning;

- overly complex sentences contain advanced, flowery vocabulary infrequently used in other contexts;

- and tangential passages filled with metaphors, similes, and allegories.

That is because in Spanish, we think in anecdotes, in stories, in tangents. We love our colourful narratives or “cuentos” (stories). When telling someone a “cuento,” we don’t go straight to the point: we give the whole background before we jump into the action, sidetracking into interesting and loosely-related additional narratives that support our main story. And that’s exactly how we don’t write or think in English.

When writing or speaking English, we don’t like disgressions.

Contrary to Spanish academic writing, English writing

- Requires that the author’s main argument is front and centre.

- Contains a linear structure: readers need a clear, from-A-to-Z structure in order to understand the information in the article.

- Tangential arguments or passages are discouraged and considered either irrelevant or confusing.

- Sentences tend to have a simpler structure, even when the author is using passive voice

In English, the reader is not meant to assume or deduct: the writer needs to do all the work. Understanding the structural differences between English and your first language can help you plan and organize your essays in a clearer way for your reader. In my experience as a teacher, writer and researcher, planning and organizing paper for an Anglophone audience is where most EAL students struggle.

Now, don’t just take my word for it. Hear what the EAL students interviewed for the Oregon State University documentary Writing Across Borders have to say about the differences between English and their first languages:

YouTube video: Towson Writing Center, Writing Across Borders (Part 1)

How can I improve my writing, then?

Here are three specific tactics I use to keep my writing projects on track:

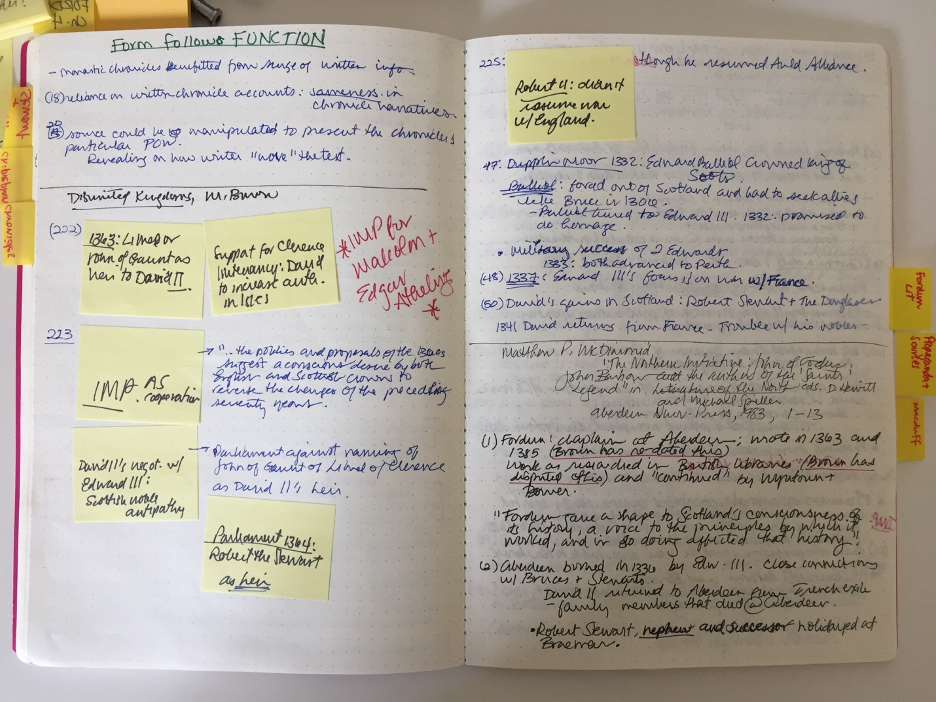

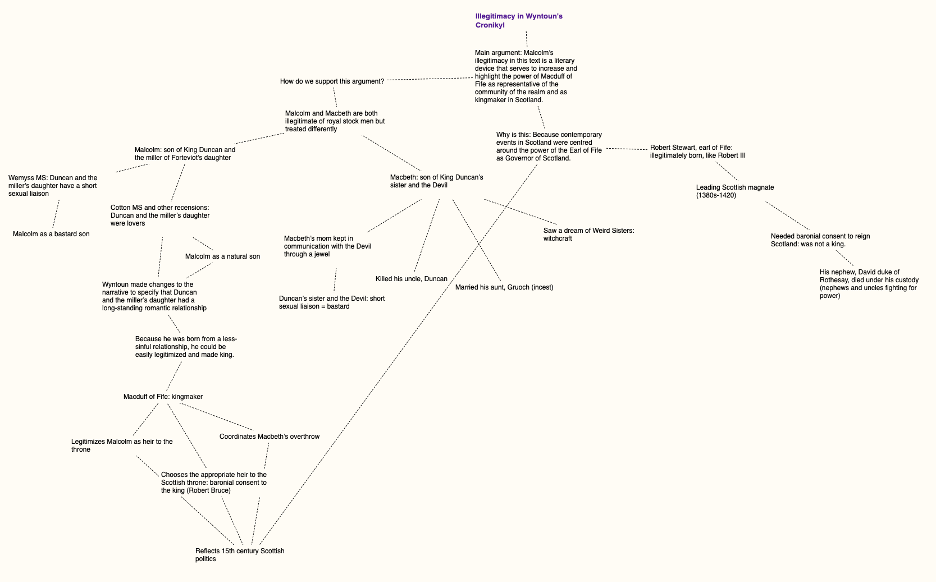

Talk it out

I get stuck all the time. In fact, I’ve spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out what I wanted to focus on in this blog post. So talking things out—to my friends, my sister on Facebook, or my WCC colleagues—helps me articulate my thoughts. It gives me the space to organize ideas and eliminate what is “puro cuento” (just story) from my papers so I can get straight to the main argument and supporting points.