Why is creativity so elusive? We see artists and poets and marvel agape at their powers of creation, but in truth creativity is a learned thing – a practice of insight and introspection. You too have the potential to produce art almost as good as the greats, if only you look in the right places. It doesn’t matter that no one’s listening. It doesn’t matter that originality is a lie. Broadcast your softest parts into the void and wait patiently for tender affirmations of love, money, and abiding validation.

1.

Smack your head against

paper, keyboard, canvas,

whatever dead thing

you’ve dragged

onto your desk.

Remind yourself that

all great art is born from pain.

2.

Wander into your kitchen,

tear through drawers,

stare with cavernous eyes at the condiments

as though they hold something worth taking away.

You are a carnivore raving, jaundiced, frothing,

and the thing you crave most is next to

the mustard.

Open the fridge again.

Open the fridge again.

3.

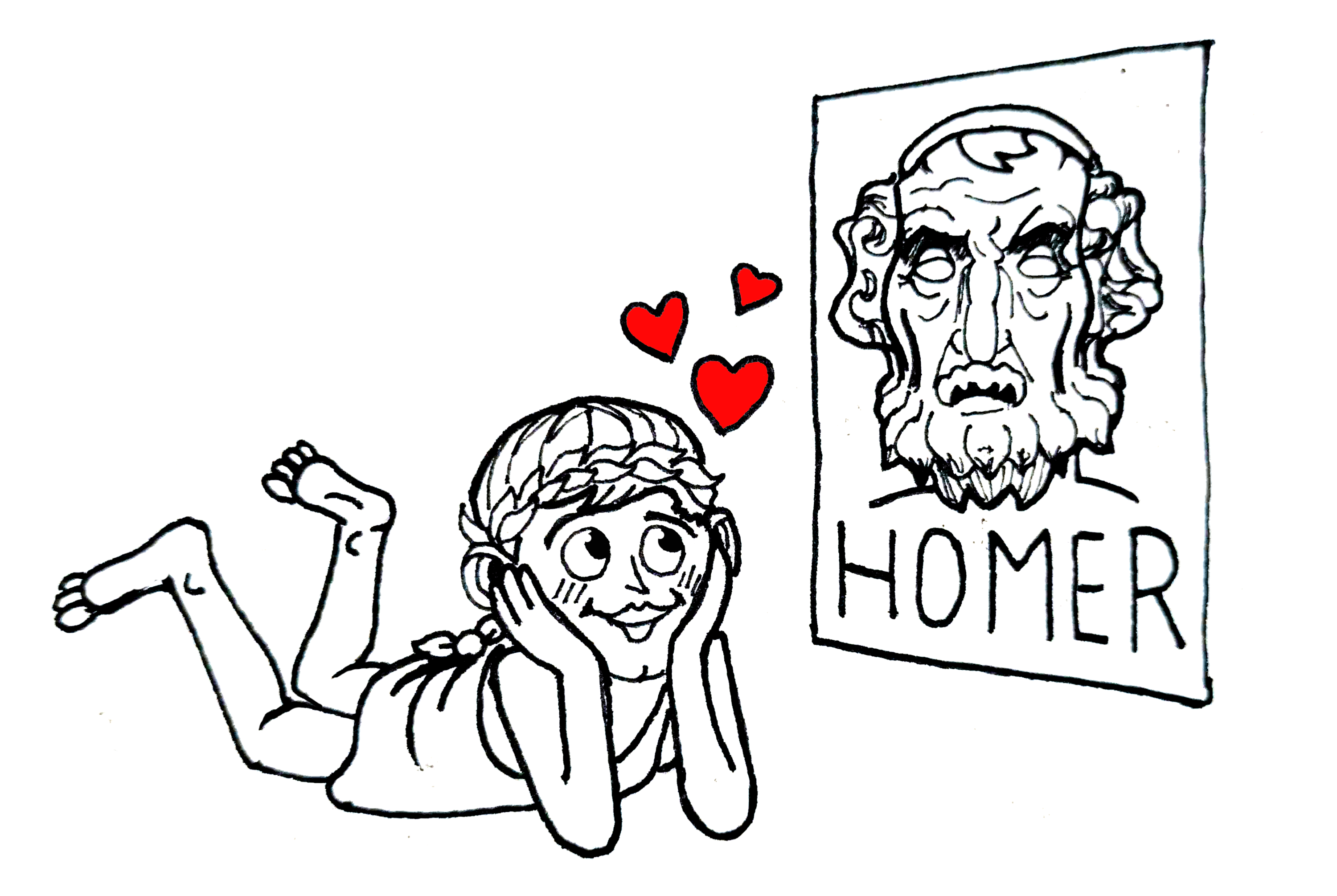

Flip through books of poetry

and bask in your inadequacy.

You will absorb through osmosis

the inspiration of strangers.

You will not remember the words,

but surely, you think, they will sink

into some soft recess at the base of your skull,

substance rising to the surface when summoned.

This is helping, you say to your eighth-favourite poet. This is work.

Burn through the pages for another hour and then

go eat lunch.

Artist statement: behind the making of a poem

Last semester, my creative writing teacher told us…

“Make a list. Write down how you get yourself in a creative mindset.”

As I can’t bear to take anything seriously, I wrote down the following:

- Bang my head off my desk.

- Walk mindlessly through my kitchen, opening drawers. What am I looking for?

- Flip through books at random while reminding myself of that Stephen King quote that says constant reading is a prerequisite to good writing and that I’m totally working and not procrastinating right now.

The joke, of course, is that these are all images of frustration. All too often I find myself paralysed at the thought of coming up with something vital and unique. I spend my weekends tearing through old notes and dusty paperbacks, all the while thinking: I can’t settle for mere imitation. I have to stand on my own. Be original. Genuine. Creative. There are things to say that have never been said, and it’s my duty to bring them into the world.

The result, unsurprisingly, is that most days I write nothing at all.

There’s a conception in the modern era of the writer as artist rather than artisan. We fawn over experimentalists—the avant-garde—who push the boundaries of convention. We watch painters and sculptors deliberately toy with our expectations, questioning the definition of art itself. The person who creates brings something into being that is new; they “make it new.”

Originality and creativity have become synonymous with quality.

But things weren’t always this way.

A history of creativity

Before 1742, the word Originality was used only in reference to original sin, or to the origin of something. It wasn’t until the late 18th Century that Romanticists (and later Modernists) popularised its current usage as “the power of independent thought or constructive imagination” (Merriam-Webster), the aspect of a work which makes it “distinguishable from reproductions, clones, forgeries, or derivative works” (Wikipedia).

With the Romanticists, difference became an ideal, and derivation a sin. A work was good not because of its inherent quality, but because it stood apart from works of the past. This seems natural to us now. Who would advocate copying? Why settle for what’s been done before?

This idea isn’t altogether wrong. But it’s odd in that, for millennia, “looking back” was the only real marker of quality.

Take Shakespeare, for instance. By our modern standards, he was a hack. Only The Tempest and Loves Labour’s Lost have no obvious source material for their plots. All his other plays are amalgams of old legends, pages torn from Plutarch’s Lives, and stories adapted from Chaucer. With Hamlet, for example, Shakespeare took an old Scandinavian legend (Amleth) and combined it with characters and scenes taken from The Spanish Tragedy, the most successful revenge-story of Shakespeare’s time. This wasn’t plagiarism; no one called it uninspired. Similarity was praised, and resemblance to classical works praised most of all.

The same was true for the Italian Renaissance. It was a rebirth of art, culture, and faith in the human spirit, yet it came about not through the independent discovery of new ideas, but through the rediscovery of Greco-Roman sensibilities. It was an evolution, to be sure, but one rooted firmly in tradition. Leonardo Da Vinci, for example, trained under the master Verrocchio, painting for rich buyers the same biblical figures depicted in nearly all Renaissance art: Jesus, the Virgin Mary, David and Goliath. However, the credit went not to Leonardo or to Verrocchio’s other apprentices, but to the master himself. The kids did the grunt-work, and he took the credit. It was his workshop, after all. The same was true for Michelangelo and Raphael. Art was a craft, not individual expression.

This trend goes even farther back. In the Roman Empire, writers copied Greek works and translated the originals into Latin. Their plays were Greek; their poetry was Greek; their genres, themes, characters—all Greek. Picking up where the Odyssey and Iliad left off, you might say Virgil’s Aeneid is an elaborate work of fan-fiction. It draws on all same techniques that Homer likely lifted from some other poet now lost to history.

If TV Tropes has proven anything, it’s that there are no new ideas. Seriously, read the Aeneid’s entry. It features over a hundred tropes, and for each trope there’s a hundred examples stretching across time. Some tropes are even older than recorded history.

Good artists copy, great artists steal

The takeaway here is this: Worry about execution, not ideation. Every possible idea has been thought of before. The greatest works of art and literature were never ‘new’ or ‘fresh,’ but merely novel arrangements of old materials.“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

And that is okay.

This, on reflection, is what my teacher meant. Being ‘creative’ isn’t about wrestling with the anxiety of influence – it’s about letting go. Following your pen wherever it takes you, even if that direction is backward. If I want to get myself into a creative mindset, the first step is to get over myself, get on the floor, and get busy with the common building blocks we’ve been playing with for millennia.