Farm scene near Bamberg, Ontario

Let’s continue our look at the protection of farms using heritage designation under Part IV of the OHA.

We’ve seen that the traditional Ontario farm consists typically of buildings — a farmhouse and farm buildings such as barns and sheds; structures — fences, windmills, and so on; “planted” and “natural” features — orchards, streams, ponds, woodlots, etc.; laneways; and of course the farm fields. Together these elements comprise the farmscape, or cultural heritage landscape of the farm.

So to have a farm CHL worthy of designation, at least on physical/design grounds, you’ll need many if not most of these features.

This was the issue before the Conservation Review Board in a 2015 case. In Quereshi v. Mississauga (City)[1] the municipality wanted to designate 2.15 acres at 2625 Hammond Road in Mississauga. The small acreage was all that was left of the original hundred acre farm once owned by the Hammond family.

Former Hammond farmhouse, 2625 Hammond Road, Mississauga

Thirty years previously the city had designated the old farmhouse on the southerly portion of the remnant parcel; it now wanted to designate the whole parcel. According to the Notice of Intention to Designate, [t]he entire Hammond property merits designation under the Ontario Heritage Act as a significant cultural heritage landscape.” The owners/objector was okay with the 1984 designation but did not want the rest of the property designated.

Would the property — the surviving rump of the original farm — qualify for designation? The city argued that the property met the 9/06 criteria as a representative example of a nineteenth century farmstead, and because of its association with the prominent Hammond family.

In terms of farm features, it was obvious from the evidence that a lot had been lost over the years. The hundred acres was last cultivated in 1967. The orchards and most of the fields had been severed and redeveloped for residential and commercial uses. Except for the former farmhouse, all of the core farm function buildings (barns, driveshed, etc.) and related infrastructure such as fences had been removed, and the site now had modern outbuildings and landscaping around the house.

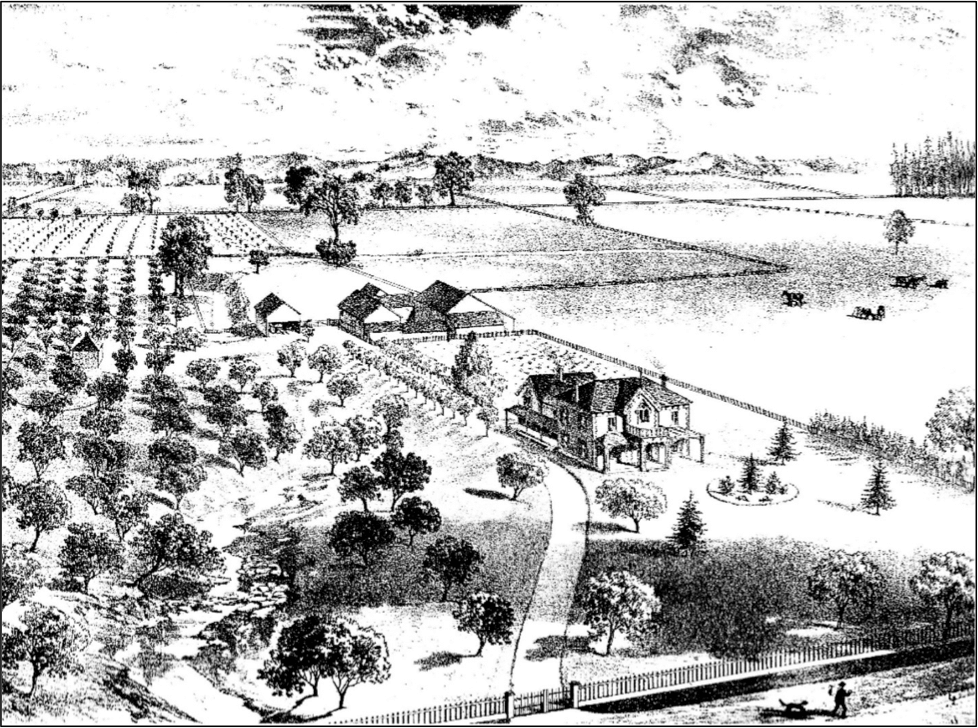

Depiction of “late Oliver Hammond, Esq., Credit, Ont,” farmstead in the Illustrated Historical Atlas of Peel County, 1877

Despite all these changes the city’s expert witness maintained that “it is still possible to distinguish elements of the traditional layout of this farmstead within the remnant 2.15 acres.”[2] These elements were identified as including the former farmhouse and its setback from the road, part of the former farm lane (now the driveway), the creek, stands of trees (renewed over time), and modern landscaping “in keeping with the traditional planting patterns."

The case would turn on the “finding [of] physical evidence within the 2.15 aces of the purposeful intent of the Hammonds … in laying out the farm.”[3] The city claimed that there was adequate evidence in this regard. The objector claimed that the surviving evidence was found on the southern, previously designated portion around the farmhouse, and not on the northern part of the property where existing “features and relationships … are simply a product of the topography” and, with respect to trees, the natural renewal of the site.

The stream was a case in point. The city argued that the watercourse was important to the locating of buildings on the farm, both for its utility as a water source and for its scenic value. The objector countered that, by the 1860s when the Hammonds built their farmhouse, the location of the dug well to the south, not the stream to the north, was the principal factor in locating the buildings on the farm. And that there was no physical evidence that the dwelling was located to exploit picturesque views of the stream (no viewing areas, terracing or steps).

The CRB concluded that the city’s case had not been made.

The Review Board finds that the City’s characterization of the property as a style or type known as a 19th century farmstead, and its interpretation that natural aspects of the property are heritage attributes that contribute to that style or type, relies too heavily on conjecture. The City did not provide clear evidence of the typical features of the style or type, and the extent to which those features were incorporated in this farmstead by the Carpenter [early settlers] or Hammond families.[4]

Ultimately the loss of farm-related attributes was fatal to the argument that a designatable cultural heritage landscape extended to the whole 2.15 acres.

It was demonstrated that many key elements that might have been characteristic of a mid 19th century farmstead, and/or might have contributed to an understanding of the Hammond farmstead in particular, have been removed from this property: the barn complex, the driveshed, fencing, the field system, boundary fences, orchards, internal laneways, the entrance feature, and the woodlot. The Review Board finds that the surviving natural features cannot substitute for this loss of heritage integrity.

As the 2.15-acre property no longer contains sufficient farm related features to be considered a representative example of a mid 19th century farmstead, it does not meet the criterion in section 1(2)1.i [of O. Reg 9/06] for design or physical value as a farmstead. … [T]he Review Board agrees with the Owners/Objector that only the southern portion of the acreage warrants continuing protection under the Act.[5]

As to the association with the Hammonds, the CRB agreed that the criterion for historical/associative value (in section 1(2)2.i) was met but found that the key heritage attribute that contributed to this value was the former farmhouse, already protected by the existing designation.

The Board therefore recommended against designation of the whole parcel and suggested the City of Mississauga consider updating the existing designation bylaw for the southern piece of the property.

Mississauga did not pursue the new designation.

Next time: We’ll look at lessons from the Banting and Hammond Road cases and apply them to a farm designation currently underway in Guelph (and also bound for the CRB).

Notes

Note 1: The CRB decision can be found here.

Note 2: At paragraph 40.

Note 3: At paragraph 51.

Note 4: At paragraph 80.

Note 5: At paragraphs 85 and 86.