It’s often pointed out that the founding year of the University of Waterloo coincides with the launch date of Sputnik I, the Soviet-built satellite that was the first artificial object put into space (October 4, 1957). The implication is that the University’s creation was part of the response by western countries to the Soviet Union’s space launch and perceived lead in international science and technology. Canada and the United States did react to the Sputnik achievement with alarm and then with educational reform and a new emphasis on science, but in fact Waterloo was well ahead of the curve — obviously, since the first engineering class at Waterloo College Associate Faculties had begun studies in July, three months before the launch from Baikonur.

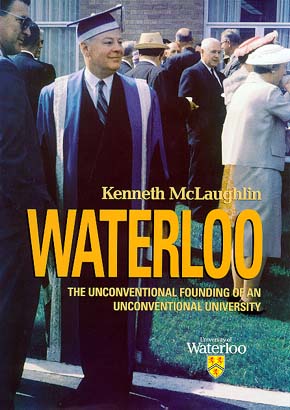

By 1955 (incidentally also the publication date of Rudolf Flesch’s Why Johnny Can’t Read, the book most associated with the rush to improve American schools in the 1950s) those in the know were already anxious about the state and size of the Canadian post-secondary education system. The initial meeting about creation of a science and technology faculty attached to Waterloo College was held late that year, and a national conference on “engineering, scientific and technical manpower” was called for the fall of 1956. Ken McLaughlin traces the events of this period in detail in his book Waterloo: The Unconventional Founding.

On August 27, 1956, the speaker at a meeting of the Kitchener-Waterloo Rotary Club was Ira G. Needles, president of B. F. Goodrich Canada Ltd. — the largest employer in the Twin Cities — who had also agreed to be chairman of the board of governors for the new Waterloo College Associate Faculties. As subsequently produced in pamphlet form, his talk runs 4,000 words, and must have taken a little more than half an hour to read. Its title was “Wanted: 150,000 Engineers and Technicians: The Waterloo Plan”.

In it, Needles traced the Canada-wide need for more highly trained “manpower”. The “150,000” figure was not originally his own, but was borrowed from an editorial that had appeared in the Globe and Mail a few weeks earlier. “The greatest product which we will realize from our electronic era,” Needles told the Rotarians, “is the better educated race. This applies in all fields — not just the field of science.… Most industries are seeking more young people with college education as a firm foundation for executive training.” He warned that “Rusia has developed the greatest program in the world for the mass education of youth.”

Another key point from the Needles speech: “The primary purpose of our institutions of higher learning has always been to produce scholars, and I hope that that will always remain the primary purpose. But we need more than the gold and silver medalists. We need the pluggers. The young people who mature later in life. The students who have determination and aggressiveness. We need to make it possible for these young people to procure a higher education.”

He described the “Waterloo Plan”: the novel idea of co-op, with academic and work terms alternating, and the training of technicians with a three-year diploma right along with engineers with a full degree. “This is the first public announcement that has been made of the Waterloo plan,” Needles said, “although it has been widely checked with the top management of many of our large companies, using engineers and technicians.”

In his book, McLaughlin records that the national conference that fall led to the creation of an Industrial Foundation on Education. Its newly appointed executive director distributed copies of Needles’s speech “to his directors, the presidents and chief executive officers of Canada’s most powerful corporations, making the Waterloo Plan and its sponsor, Waterloo College Associate Faculties, known throughout Canada.” A copy of the resulting pamphlet is in the university archives.

Students Surveying, Paul Kuntz, Kitchener, Larry Moss, London, Summer 1959. University of Waterloo Library Special Collections & Archives.

The goal of 150,000 engineers and other educated Canadians from the University of Waterloo was achieved in October 2010, says Jason Coolman, the director of alumni affairs, who reports (e-mail, January 2012) that “As of December 2011 Waterloo has 158,652 alumni,” including 32,831 from engineering.