New diabetes device monitors blood using radar and AI, not painful pricks

A palm-sized device developed by researchers at the University of Waterloo uses radar and artificial intelligence (AI) to non-invasively read blood inside the human body.

New technology can quickly and accurately monitor glucose levels in people with diabetes without painful finger pricks to draw blood.

A palm-sized device developed by researchers at the University of Waterloo uses radar and artificial intelligence (AI) to non-invasively read blood inside the human body.

“The key advantage is simply no pricking,” said George Shaker, an engineering professor at Waterloo. “That is extremely important for a lot of people, especially elderly people with very sensitive skin and children who require multiple tests throughout the day.”

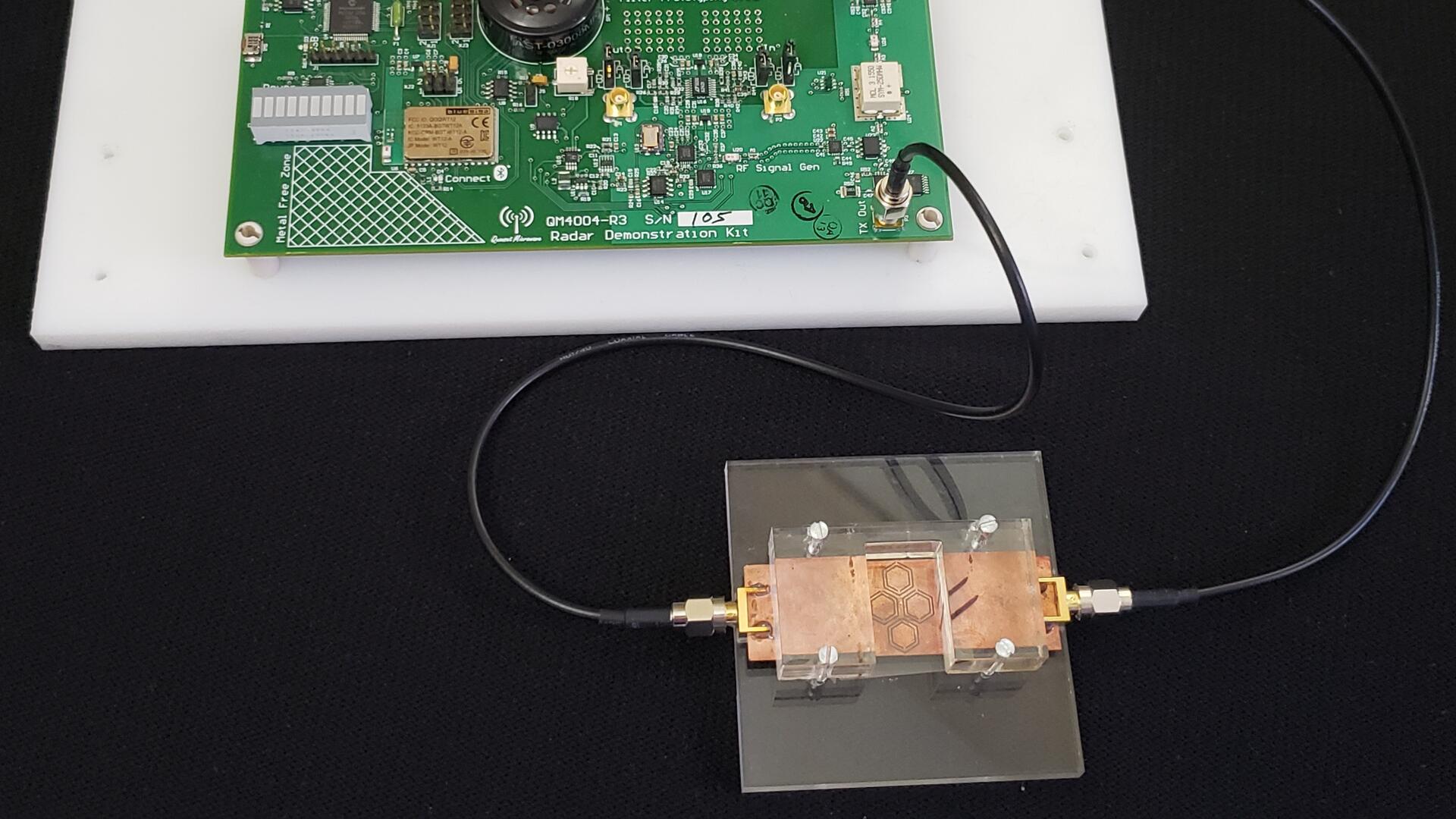

Researchers test a prototype of a new diabetes device for prick-free glucose monitoring.

About the same size as existing glucometers, the rectangular device works by sending radio waves through the skin and into blood vessels when users place the tip of their finger on a touchpad.

The waves are then reflected back to the device for signal processing and analysis by AI software, telling users within seconds whether their blood sugar has gone up, down or remained the same.

Changes are measured in relation to a baseline reading that would be obtained every few weeks with a glucometer or a laboratory blood test to ensure accuracy.

“Our safe, reusable, pain-free device would eliminate the need for implanted sensors, patches or devices that use chemical reactions or fluid transfer through the skin,” said Ala Eldin Omer, an engineering PhD student who led the project.

Researchers are now exploring commercialization of the inexpensive technology - they estimate the device would retail for less than $500 - and developing a wearable device similar to a smartwatch that would be on at all times.

“This finding paves the way for continuous monitoring,” said Shaker. “Given the current pace of progress, I expect the technology to be available in a wearable form within the next couple of years.”

Safieddin (Ali) Safavi-Naeini, also an engineering professor at Waterloo, said the science at the heart of the diabetes device potentially has several additional applications.

"Since many ingredients of blood have distinct electromagnetic properties, the same technology could be extended to other types of blood analysis and medical diagnosis," he said.

Much of the work was conducted at the Wireless Sensors and Devices Lab and the Centre for Intelligent Antenna and Radio Systems (CIARS) at Waterloo. Collaborators included several researchers at Sorbonne University in Paris.

A paper on the project, Low‑cost portable microwave sensor for non‑invasive monitoring of blood glucose level: novel design utilizing a four‑cell CSRR hexagonal configuration, appears online in Scientific Reports, a Nature Research journal.