On July 16, 1945 the United States Army successfully detonated the first atomic bomb in the desert of New Mexico. Codenamed Trinity, the test marked a pivotal moment in history, as it demonstrated the feasibility of atomic weapons – ultimately leading to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

With the recent box office success of Oppenheimer, discussions surrounding the Trinity test and the subject of nuclear war are resurfacing. Mary Kavanagh’s exhibition, Trinity, Then and Now, located in the Grebel Gallery at the Kindred Credit Union Centre for Peace Advancement, explores the test’s lasting impact in a narrative context. All are invited to visit the gallery and explore Kavanagh’s compelling work dedicated to highlighting the complex ramifications of nuclear testing.

Kavanagh is an artist and Professor in the Department of Art at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta. She is a Tier I Board of Governors Research Chair (2020-2025), awarded for her work examining the material and embodied evidence of war and conflict, nuclear culture, and scarred landscapes, and her artwork has been exhibited across Canada and internationally.

Kavanagh describes the atomic bomb as “the ultimate act of creation and destruction.” There is a profound duality in these words. Scientifically speaking, the atomic bomb releases immense amounts of energy, far greater than that of any other human invention. It is a remarkable achievement to harness the fundamental forces of this very universe. Destruction, on the other hand, lies in the very implications of the bomb’s existence. Once the bomb has been unleashed, the ecological and human toll is irreversible.

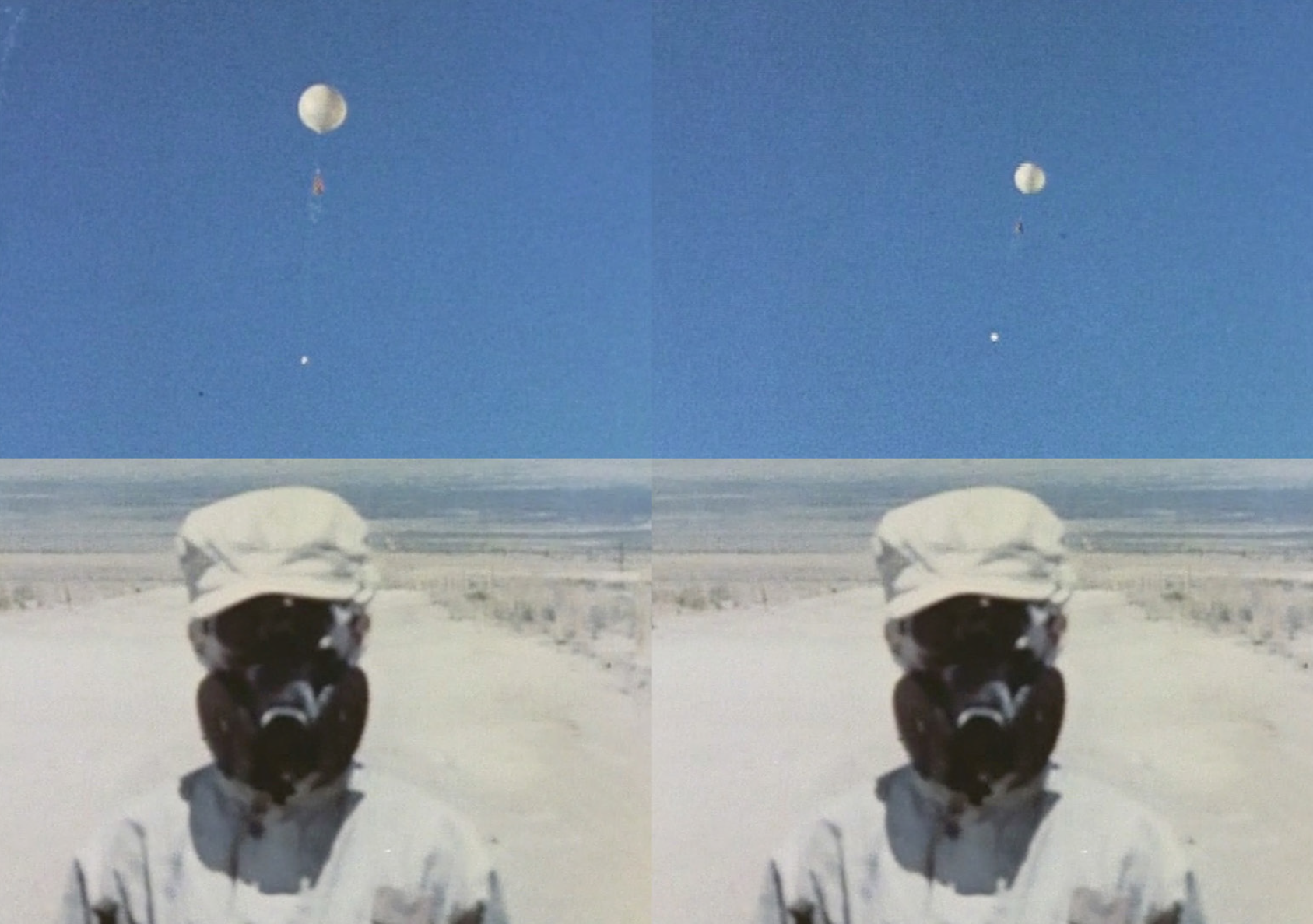

The narrative of Trinity, Then and Now walks audiences through pieces of archival footage that display the building of the bomb, the heavily propagandized Cold War Nuclear Testing Program, and the violent Earthly repercussions caused by the morbid relationship between humans and nuclear technology.

Many seem to speak about nuclear war and Trinity as relics of the past. The legacy of nuclear war extends beyond one single event. The radiological toll of bombs such as Trinity have devastated and continue to devastate human life (specifically Indigenous populations) and fragile ecosystems. In this context, one may wonder how nuclear testing and nuclear war are truly differentiated.

Trinity, Then and Now represents only a small piece of Mary’s research focused on the long-term impacts of nuclear armament. Her large-scale project, titled Daughters of Uranium, explores the continuous psychological, ecological, and physical trauma that is triggered by nuclear armament. The name symbolizes the radioactive decay chain of Uranium 235, an isotope present in the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

The exhibition will be featured in the Grebel Gallery until February 28, 2024. Visitors are invited to drop in to see Trinity, Then and Now during the gallery’s regular hours, Monday through Thursday from 8:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., and 8:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. on Fridays. Questions, feedback, or group inquiries should be directed to Centre for Peace Advancement Coordinator Fatoumatta Camara (cpacoordinator@uwaterloo.ca).

The Gallery will be hosting Mary Kavanagh from November 7 to 9. Opportunities to engage with her during this time will be publicized in the coming weeks.

By: Sophia Pettit