Profiles

We're launching a set of profiles about some of the more famous or interesting items out the collection, starting with a few that are currently on display in DC 1316. We'll publish more profiles later this fall.

Apple Macintosh

by Anthony Huynh

The first Apple Macintosh was announced in October 1983 and introduced on January 24, 1984 by Steve Jobs.

The idea for the Macintosh was conceived by Jef Raskin, an Apple employee who dreamed of an intuitively designed and affordable computer for the average person. He chose to name the computer after his favourite apple, the McIntosh, but due to legal reasons, he had to change spelling to Macintosh.

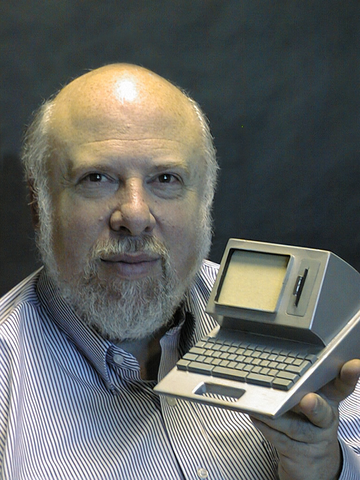

Jef Raskin (c.1999), holding a model of the Canon Cat. (Credit: CC BY 2.0 Wikimedia)

In September 1979, Raskin had been approved to start hiring for his project. His main cooperative partners were Bill Atkinson, who was part of Apple’s Lisa team, which was developing a similar but more advanced computer, and Burell Smith, who was recently hired as a service technician. Smith designed the first Macintosh board with 64 kilobytes (Kb) of RAM, the Motorola 6809E microprocessor, and to support a 256 × 256 pixel black-and-white bitmap display. Bud Tribble suggested to Smith to improve upon his design by using the Motorola 68000 microprocessor (the same as was being used on the Lisa computer). It was one of the most powerful CPUs at the time and could help maintain a low manufacturing cost. Smith would successfully implement Tribble’s suggestion in December 1980, which increased the clock speed from 5 to 8 megaHertz and gave it the capacity to support a 384 × 256 pixel display. The design of the board maintained its cost-efficiency by using fewer RAM chips than the Lisa. The final design for the product would include 64Kb of ROM, 128 Kb of RAM, a 9-inch screen, and a 512 × 342 pixel monochrome display.

This project would soon catch the attention of Steve Jobs as he realized the Macintosh had a lot more marketing potential than the Lisa. The increased involvement from Jobs would lead Raskin to leave the project in 1981 due to a personality clash with Jobs, which would ultimately cause Jobs to have much more significant impact on the final design of the Macintosh than Raskin. Jobs was heavily interested in the innovative GUI technology being developed at Xerox PARC, so he negotiated a deal to see some of the technologies and development tools which were used at Xerox in exchange for Apple stock options. Xerox PARC’s GUI technology had already influenced Apple’s work on the Lisa, but now that he had a more in-depth knowledge of the same technology, he applied it to the Macintosh.

Apple invested a significant amount of effort in promoting the Macintosh including spending over US $2.5 million to appear on all 39 advertising pages of the special post-election edition of Newsweek magazine. They also funded a promotion event for the Macintosh where potential consumers could borrow a Macintosh for 24 hours, which proved to be a mistake due to low supply and because many were returned in conditions unfit to be sold. To make up for these costs, Apple raised the price from US $1,995 to $2,495.

Photograph of Apple Lisa computer (Credit: CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia/Timothy Colegrove)

However, the most iconic and memorable Macintosh promotion was a 1984 Superbowl commercial, which was directed by Ridley Scott, who also directed Blade Runner, Alien, and later, Gladiator. The commercial opens with a shot of numerous bald men in gray outfits walking uniformly in a long straight line down an industrial tunnel in an extremely dreary atmosphere. Then it cuts to a shot of a woman in a white top and orange shorts holding a sledgehammer running down a tunnel being chased by guards in security gear. It’s revealed that all these men are walking towards benches in front of a large blue screen projecting the face of a man, resembling Big Brother, who is indoctrinating these lifeless men. When the woman reaches the screen, she swings and throws the sledgehammer at the screen, resulting in a bright explosion and a gust of wind blowing against the astonished looking men. A message scrolls upwards saying, “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like '1984.’ ” Even though this commercial didn’t outright advertise the Macintosh itself or any of its features, except for a brief mention at the end, it was still very effective in generating a lot of excitement in the media, which is how it managed to sell 250,000 units by the end of 1984. This convinced other advertisers that commercials didn’t need to outright feature the product they were selling to make an effective promotion and create lots of publicity. Apple estimated that the resulting conversation and ad replays in the media gave the Macintosh over US $150 million of free advertising and airtime. An influential aspect of this commercial, many have argued, is that it led to the modern era of Superbowl advertising, where the halftime ads are as entertaining or looked forward to as the game itself. The Macintosh was so revolutionary that even Bill Gates stated that “To create a new standard takes something that’s not just a little bit different. It takes something that’s really new and captures people’s imaginations. Macintosh meets that standard.”

Apple 1984 Video

The original Macintosh was the first commercially successful personal computer to feature the mouse and a graphical-user interface (GUI), as opposed to the less friendly command-line interface (CLI). The difference between the GUI and the CLI is how users interact with the computer. On the one hand, the command-line interface lets the user input text commands into a console or terminal window. When the user types a command, the terminal interprets the command and executes the requested task. This user interface is extremely similar to coding or programming which means it’s required that you have proficient knowledge of different commands, their syntax, and what they can do. On the one hand, the CLI is harder to use and understand, it is significantly more effective than the GUI as it is more memory efficient and performs tasks faster. On the other hand, the graphical-user interface is mainly based on graphics and visual elements, allowing users to interact using a keyboard and mouse. The emphasis of the GUI is on user-friendliness and system management as it provides windows, various menus, buttons, and icons which makes interaction with the interface a lot more intuitive. Click here and here for more info on the difference between the graphical-user interface and the command-line interface.

This Apple Macintosh GUI ended up influencing the entire personal computer market. Even though Apple did not invent GUI technology and it would not become common until 1990 with the release of Windows 3.0, Apple paved the way for a mainstream personal computer GUI.

Although the Macintosh was a successful and revolutionary device, it still had its fair share of limitations. Some of which include limited memory and lack of a hard disk drive or the means to easily connect one. On September 10, 1984, Apple would release the second model of the Macintosh, the Macintosh 512K, and increase the memory capacity of the Mac to 512 Kb but they found that it was difficult and inconvenient to increase the memory capacity from 128 Kb to 512 Kb when using the original model. To fix some of these flaws, Apple decided to release the Macintosh Plus on January 10, 1986, which not only was an immediate success, but it also proved its longevity as the longest lasting Macintosh in production, until October 15, 1990 (4 years and 10 months). The Macintosh Plus came standard with 1 megabyte of RAM, and a maximum capacity of 4 megabytes, and a revolutionary SCSI parallel interface which could connect seven peripheral devices to the computer simultaneously. In addition, the Macintosh Plus was the first Apple device released after Job’s resignation on September 16, 1985, due to a power struggle of control over the company with John Sculley.

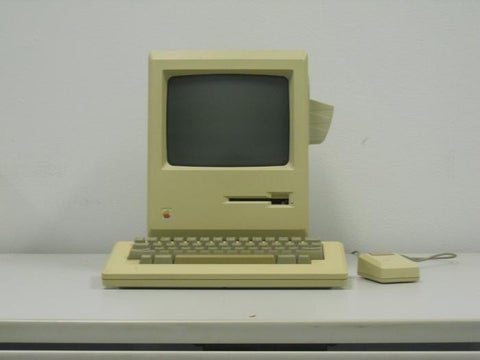

Apple Macintosh (UWCM 2016.7.9)

Photograph of Apple Macintosh in collection (UWCM 2016.7.9)

(Link: UWCM 2016.7.9)

The Mac Plus was the first Macintosh model to include a SCSI port, which started the popularity of external SCSI devices for Macs, including hard disks, tape drives, CD-ROM drives, printers, and even monitors. SCSI ports remained standard equipment for all Macs until the introduction of the iMac in 1998. The Macintosh Plus was the last classic model to have a port resembling that of a phone cord in front of the keyboard, as well as the DE-9 connector for the mouse since later models would use ADB ports. It had a new 3.5-inch double-sided 800 KB floppy drive, offering double the capacity of previous Macs along with backward compatibility. The 800 KB drive had two read/write heads, enabling it to simultaneously use both sides of the floppy disk and thereby doubling the storage capacity.

The Mac Plus was the first of several Macintoshes to use SIMMs (single in-line memory modules) for its memory. It had 128 KB of ROM on the motherboard, which was double the amount of ROM that was in previous Macs; the new System software and ROMs included routines to support SCSI and the new 800 Kb floppy drive. In addition to the typical MacWrite and MacPaint that came along with the Macintosh, the Macintosh Plus included the convenient HyperCard and MultiFinder which allowed users to multitask and use multiple applications simultaneously. Like the previous Mac models, the Plus still did not provide adequate support for an internal hard drive, and it would take over 9 months before Apple would offer a SCSI drive replacement for the slow Hard Disk 20. It would take well over a year before Apple would offer the first internal hard disk drie in any Macintosh. The Plus had a 9-inch, 512 x 342 pixel monochrome display with a resolution of 72 PPI, identical to that of previous Macintosh models. Unlike earlier Macs, the Mac Plus's keyboard included a numeric keypad and directional arrow keys, and, as with previous Macs, it had a one-button mouse and no fan, making it extremely quiet during performance.