Accidental guardians: How reservoirs are decreasing nitrogen and phosphorus loads reaching Lake Winnipeg

A WaterLeadership Snapshot

WaterLeadership Snapshots feature articles written by graduate students participating in the Water Institute’s WaterLeadership training program, which focuses on skills development in knowledge mobilization, leadership, and research communication. Here, students describe the value of their research and its potential for ‘real world’ impact.

By Noelle Starling

Lake Winnipeg has been experiencing increasingly severe algae blooms since the 1990’s, earning it the title of “Canada’s Sickest Lake”. This “illness” stems from excess nutrients, primarily phosphorus and nitrogen, running off from agricultural lands, urban areas, and wastewater treatment plants. These nutrients result in various water quality problems, including excessive algae growth, which can block light, deplete oxygen levels, and release toxins into the water.

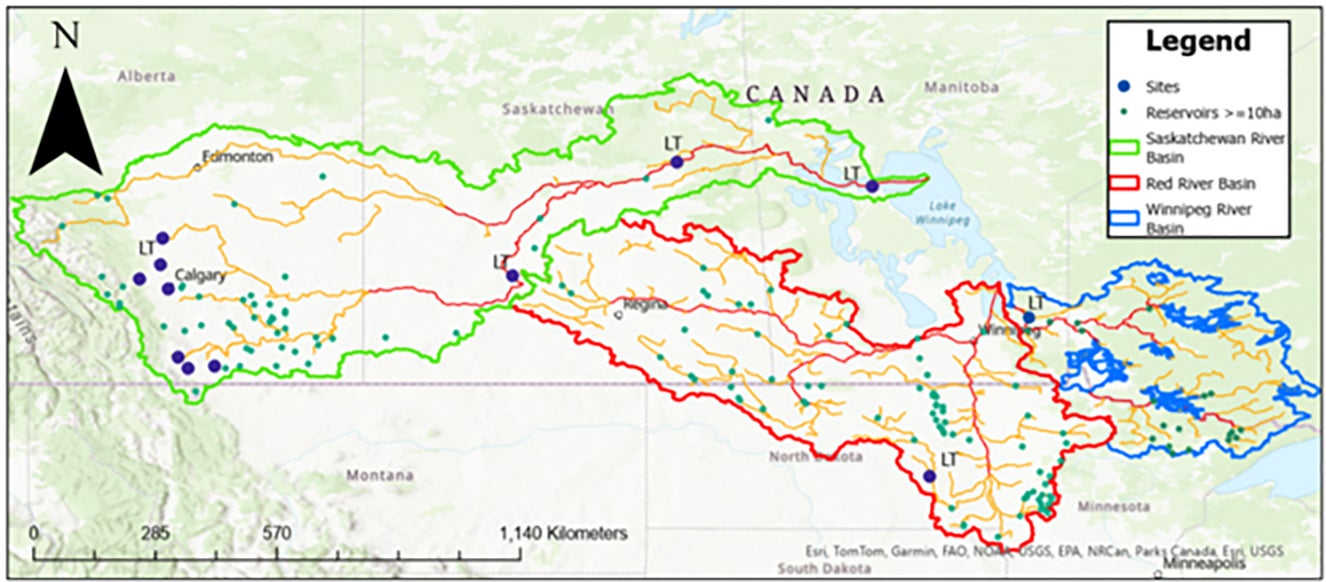

Map shows the three main sub-basins that drain to Lake Winnipeg, the Saskatchewan river (green), Red River (red) and Winnipeg River (blue). Sites used in the study are marked in blue dots and dammed reservoirs >10ha in surface area are marked in green dots.

The Lake Winnipeg Basin, which spans four Canadian provinces and four American states, is home to diverse wildlife, including many migratory birds. It also supports a $102 million fishing industry, making its health an international issue. To restore and protect one of Canada’s largest freshwater lakes, we must put Lake Winnipeg on a nutrient diet.

Masters student Noelle Starling, under the supervision of Dr. Philippe Van Cappellen of the University of Waterloo’s Ecohydrology Research Group and Dr. Chris Parsons of the Watershed Hydrology and Biogeochemistry Group at Environment and Climate Change Canada, is investigating how reservoirs trap nitrogen and phosphorus across the Lake Winnipeg Basin.

How does existing water infrastructure impact downstream nutrient loads?

Using data from 12 case-study reservoirs monitored for water quality (e.g., nutrient levels) and quantity (water volume), Starling can estimate how much nitrogen and phosphorus enter and exist these dammed reservoirs.

A key priority of the project is promoting the importance of publicly available water quality monitoring. Whenever possible, Starling uses open access datasets provided by The Water Survey of Canada (water quantity) and those provided by a range of government, academic and NGO organizations accessible via the DataStream platform (water quality).

What have we learned so far?

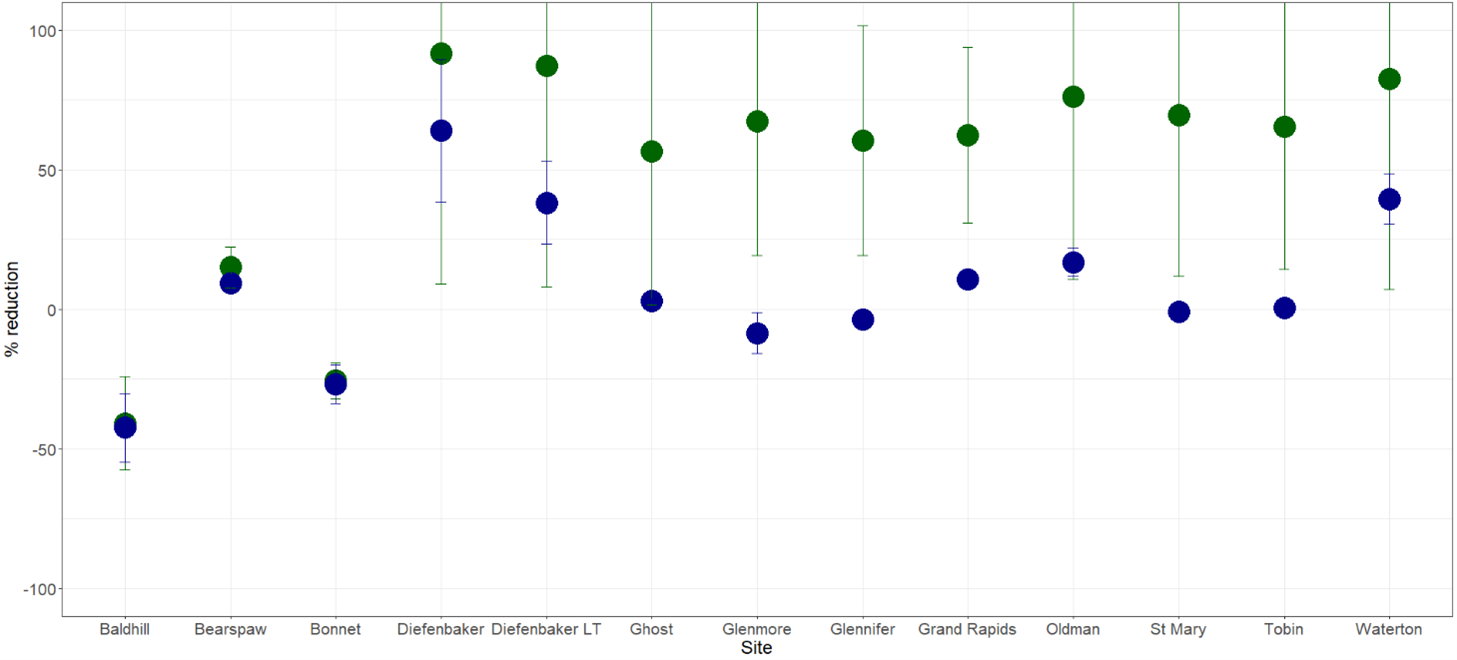

Preliminary results indicate that:

- Among the 12 reservoirs studied, the amount of phosphorus decreased by an average of 51.4%, and the amount of nitrogen decreased by 7.67%.

- Dams may be helping to suppress the annual nutrient surge that occurs during spring snowmelt.

The graph shows estimated average annual % reduction in the total phosphorus (green) and total nitrogen (blue) loads across each dammed reservoir. Estimates were made using the WRTDS method. Flow data from Water Survey of Canada and concentration data of TN and TP from City of Calgary, Government of Saskatchewan, Government of Manitoba, Government of Alberta, and Government of Canada.

What’s Next?

The next steps in the project will focus on identifying the characteristics of reservoirs with very high retention rates and assessing the collective impact of the 156 large reservoirs (over 10 hectares in area) across the Lake Winnipeg Basin on nutrient loads.

Understanding how reservoirs reduce and shape nutrient loads is just one piece of the puzzle that will help tackle the challenge of reducing nutrient loads. Other initiatives, such as improved agricultural practices and enhanced water treatment, are also being implemented through the Lake Winnipeg Basin Program. Understanding how and when reservoirs influence nutrient pollution provides decision makers and stewards with an additional tool to combat eutrophication and algae blooms—helping to make Lake Winnipeg a little less green.