Achieving water quality goals for the Gulf of Mexico may take decades, according to findings by Water Institute researchers at the University of Waterloo.

The results, published today in Science, suggest that policy goals for reducing the size of the northern Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone may be unrealistic, and that major changes in agricultural and river management practices may be necessary to achieve the desired improvements in water quality.

The transport of large quantities of nitrogen from rivers and streams across the North American corn belt has been linked to the development of a large dead zone in the northern Gulf of Mexico, where massive algal blooms lead to oxygen depletion, making it difficult for marine life to survive.

“Despite the investment of large amounts of money in recent years to improve water quality, the area of last year’s dead zone was more than 22,000 km2—about the size of the state of New Jersey,” said Kimberly Van Meter, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Waterloo.

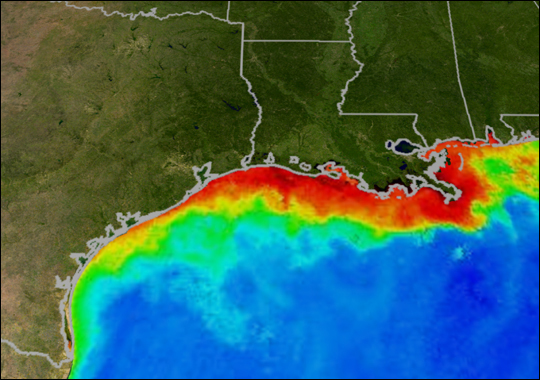

Sediment-laden

water

containing

high

concentrations

of

soil,

fertilizer,

other

nutrients

pours

into

the

northern

Gulf

of

Mexico

from

the

Atchafalaya

River

in

this

photo-like

image,

taken

by

the

Moderate

Resolution

Imaging

Spectroradiometer

(MODIS)

on

NASA’s Aqua satellite

on

April

7,

2009. Image

credit:

NASA.

Sediment-laden

water

containing

high

concentrations

of

soil,

fertilizer,

other

nutrients

pours

into

the

northern

Gulf

of

Mexico

from

the

Atchafalaya

River

in

this

photo-like

image,

taken

by

the

Moderate

Resolution

Imaging

Spectroradiometer

(MODIS)

on

NASA’s Aqua satellite

on

April

7,

2009. Image

credit:

NASA.

Using more than two centuries of agricultural data, the scientists show that nitrogen has been accumulating in soils and groundwater over years of intensive agricultural production and will continue to make its way to the coast for decades.

Water quality has become increasingly impaired in the northern Gulf of Mexico since the 1950s, largely due to both intensive livestock production and the widespread use of commercial fertilizers across the Mississippi River Basin. Manure and fertilizer are rich in nitrogen, a nutrient that boosts crop production, but when present in excess can pose a threat to both human health and to aquatic ecosystems.

We are seeing long time lags between the adoption of conservation measures by farmers and any measurable improvements in water quality,” said Prof. Nandita Basu, senior author of the study.

Modelling results from the current work show that even under best-case scenarios, where effective conservation measures are immediately implemented, it will take on the order of 30 years to deplete the accumulated excess nitrogen currently stored within the agricultural landscape.

“This is not just a problem in the Mississippi River Basin,” says Basu, an associate professor cross-appointed between the departments of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth and Environmental Sciences. “As the need for intensive agricultural production continues to grow, nitrogen legacies are also increasing, creating a long-term problem for coastal habitats around the world.”

The research team includes Prof. Philippe Van Cappellen, Canada Excellence Research Chair in Ecohydrology and a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

The group is currently extending their analysis to phosphorus, a major driver of algal blooms in the Great Lakes and other inland waters.

By Victoria Van Cappellen, Faculty of Science

In the media:

Gulf of Mexico dead zone not expected to shrink anytime soon, Exchange Magazine

Gulf of Mexico 'dead zone' will persist for decades, USA Today

Study: 'Legacy' Nitrogen Also Feeds Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone, The New York Times