Berry good news

Climate change, armed conflict, economic and political instability and natural disasters can all impact food security. And the recent COVID-19 pandemic and global inflation have added additional strain to sustainable food production and food security.

Last year, 2.3 million people, or one in six households, in Ontario were food insecure according to the 2021 Household Food Insecurity in Canada study. The production of sustainable, locally grown foods is key to providing long-term food security for communities. Eating local reduces the economic and environmental impacts of food transportation, supports local producers and farmers and produces tastier and more nutritious fruit and vegetables.

Investing and incentivizing domestic food production is already in play in Canada. The Homegrown Innovation Challenge is a six-year, $33-million initiative from the Weston Family Foundation to future-proof food production in Canada. Launched in February, the Challenge supports new solutions that reduce Canada’s reliance on imported fresh produce and builds resilience of food systems.

Through its’ three phases (Spark, Shepherd, Scale) the Homegrown Innovation Challenge encourages teams to create and deliver a market-ready system to reliably, sustainably and competitively produce berries out of season and at scale in Canada.

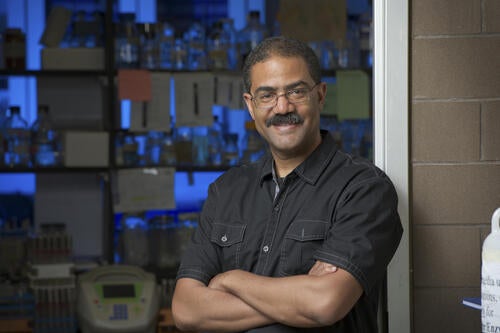

Dr. Trevor Charles, a professor in the Department of Biology and director of Waterloo Centre for Microbial Research, and his team were one of the fifteen teams awarded Spark funding by the Homegrown Innovation Challenge.

“We need to be intentional and creative in how we address food insecurity in Canada,” says Charles, project lead and CEO of Metagenom Bio Life Science. “Controlled environment food production is one of the ways to ensure that Canadians have year-round access to fresh and nutritious local produce.”

Dr. Trevor Charles, professor in the Faculty of Science, University of Waterloo

Demand for fresh, local products is at an all-time high and Canada’s strawberry market is adapting to answer the call. Traditional agricultural techniques, where crops are grown on land, are challenging since they simply do not produce enough food per acre to meet demand.

Indoor farming, like greenhouses, vertical farming and hydroponics, is a promising solution to ensure people have access to high-quality, locally grown, nutritious food that is abundant and safe. They produce greater yields in less space and with reduced crop loss from disease and natural disasters.

Charles partnered with colleagues from McGill, École de technologie supérieure and Vertité, a hydroponic strawberry grower in Montreal to refine Vertité’s growing system to achieve sustainable, year-round strawberry production in Canada.

Given Canada’s northern latitude and short growing season, it is highly dependent on imports to satisfy demand for fresh fruit throughout the year and had a trade deficit of almost $5.8 billion in 2020.

In the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s most recent fruit industry report, Canada is one of the largest importers of strawberries globally. Strawberries were among the top three fruit imports by dollar value after grapes and bananas.

The team will focus on improving indoor farming in Canada to help fill the gap for homegrown strawberries out of season. Together, they will combine their expertise in microbiology, agriculture, automated technology, imaging technology, life-cycle analysis, improved system geometry and ventilation to produce healthy, flavourful Canadian strawberries all year-long.

“This project brings together a strong interdisciplinary team of academic and industry partners to tackle key challenges in sustainable, year-round production systems in Canada,” Charles says.

Charles is focused on optimizing the plant’s microbiome to keep disease out, improve growth and increase yield. Working with Metagenom Bio Life Science and its new AgTech-focused subsidiary Healthy Hydroponics InnoTech, he will use DNA sequencing to evaluate the microbiomes of hydroponic systems and strawberries grown with the addition of beneficial microorganisms.

Samples from the circulating water will be collected and analyzed every two weeks throughout the growth cycle. Like a fingerprint, the analysis will provide the identity and proportion of each individual microbe to determine the microbial community structure and that information can be used to improve strawberry yield and quality.

“Genomics-based microbiome analysis is a powerful approach that provides a window into the microbial world that is data rich,” Charles says.

They will also add various bacteria that have been proven successful with other indoor crops, like lettuce and tomatoes, to see how the bacteria impact strawberries. Root rot is another large concern that can affect yield. Charles and his team will also try to use microbes to keep the plants strong and healthy to prevent root rot.

Additionally, they will use microbial technology to facilitate growing healthy, flavourful strawberries. This is done by isolating beneficial microorganisms such as endophytes —microbes that reside within the plant tissues — that produce compounds “fueling up” the plant’s metabolism to produce flavour compounds, antioxidants and enzymes.

In tandem, they will identify and monitor the optimal hydroponic strawberry microbiome giving rise to high-yielding strawberry plants that are robust against diseases, like root rot.

Charles’ colleagues at McGill will develop imaging technology to determine the optimal picking time. Camera-mounted robots and environmental sensors will collect data on flower, fruit and disease development. The data collected will be used to develop computational models using AI to evaluate and adjust inputs to optimize sustainable farming practices.

Having successfully passed phase one, the team will now refine their concepts, develop their teams and prepare for phase two, the Shepherd phase. Results from the second phase of the competition will be announced in Spring 2023.

Banner photo courtesy of Vertité. People featured are (L to R): Elena Fortin-Kochieva (Farm Manager), Phil Rosenbaum (Co-founder), Ophelia Sarakinis (Co-founder and CEO).