Significant built heritage resources and significant cultural heritage landscapes shall be conserved. ~ PPS policy 2.6.1

We’re looking at recent cases where the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) has explored the meaning of “conserved” — and whether demolition of a built heritage resource is necessarily antithetical to provincial planning policy.1

Last time we saw that it was okay to use the word “demolition” in an Official Plan policy outlining the range of actions to which a significant heritage structure might be subject. In other words, the LPAT did not find that a municipal policy that contemplated demolition “in whole or in part” as a possible outcome was inconsistent with the PPS.

The case today is quite different. It involves not a policy that includes the possibility of demolition but a proposal entailing the actual demolition of a significant building within a heritage conservation district.

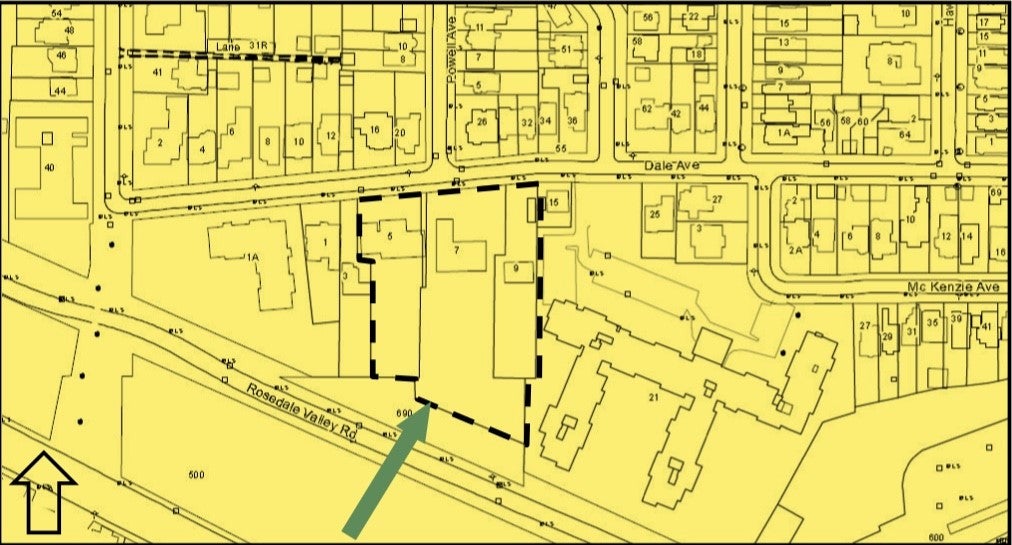

A July 4 decision of the LPAT okayed a low-rise condo development in the South Rosedale Heritage Conservation District in Toronto.2 A new four storey, 26 unit building will supplant three mid-century houses on the site, known as 5, 7 and 9 Dale Avenue, located on the edge of the Rosedale Valley ravine.

The main issue in the case was whether demolition of the three houses could proceed, clearing the way for the needed OP and zoning by-law amendments. Was the destruction of the houses consistent with the “shall be conserved” policy in the PPS (and a similar statement in the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe)?3

A partial plan of South Rosedale showing the three properties in question

The developer wanted the buildings gone, the neighbourhood residents association wanted them saved, and the city… well, first it looked like it would say no, but finally, after much negotiation and reworking of the development proposal, it came around to endorsing the project, subject to a number of conditions. This left the South Rosedale Residents Association (SRRA) as the party opposing the redevelopment at the LPAT hearing.

South Rosedale was designated and its HCD plan adopted in 2003, before the 2005 changes to the OHA. The plan’s guidelines, while not binding, provide guidance to decision-makers and the LPAT accorded them that status in its decision.4

Somewhat unusually, this particular district plan uses an A-B-C rating regime to score the significance of properties in the district.5 Properties are assigned to one of four categories: A, B, C or unrated. Properties rated “A” are individually outstanding and have actual or potential national or provincial significance, properties rated “B” are noteworthy for their overall quality and have local significance, and those rated “C” contribute to the heritage character and context of the neighbourhood. Properties that are unrated do not contribute to the heritage character of South Rosedale.

The Daly Avenue houses were given a “C” rating. With respect to demolition, the plan says that demolition of “C” buildings “is generally considered appropriate only if the proposed replacement building, as shown in the issued building permit, is equally able or more able to contribute to the heritage character of the district and is acceptable under these guidelines and the zoning by-law.” (Emphasis added.) For “A” and “B” buildings, by comparison, demolition “is to be vigorously opposed through the utilization, if necessary, of all heritage preservation protections afforded by law.”

7 Dale Avenue as seen from the street

Now it turns out that one of the properties, 7 Dale Avenue, was more significant than first appeared. Evidence at the hearing revealed that the house, constructed in 1944-45, was designed by award-winning Toronto architect Gordon Sinclair Adamson and that the landscaping was the work of prominent landscape architects Dunington-Grubb and Stenesson.

The SRRA argued that 7 Dale would handily satisfy the Reg. 9/06 criteria for individual designation under the OHA and should in fact be rated as a “B” not a “C” in the district plan (and that therefore, following the guidelines, its demolition should be “vigorously opposed”).

How then did the LPAT square its decision to approve the development and consequent loss of the Dale Avenue buildings with the PPS direction that significant built heritage resources be conserved?

In the first place, on the significance question, it appears the Tribunal was not especially impressed.

Having found that the plan and its categorizations of properties in the district were advisory only, the LPAT was free to draw its own conclusion as to the significance of the Dale houses, and did so: “On the Tribunal’s perception of the evidence, the existing structures have characteristics of middling interest for which there are limited grounds of value and minimal motivation to preserve.”6

The finding of the houses’ “middling interest” seems to have opened the door to a novel interpretation of what it meant to “conserve” the cultural heritage resources here (and what exactly these were). The Tribunal noted the history of the site, which in the later nineteenth century was occupied by a large Victorian house overlooking the ravine. The original property had then been subdivided, the building demolished, and the current houses built in the mid-twentieth century.

It is thus conceivable to view the present development proposal as a character of return to the heritage of the Property in having the severed land segments reunited as a single parcel of land accommodating a significant residential structure. In a long view, the Property has a heritage of being a bold promontory overlooking the valley below, accommodating a structure of physical presence. In this sense, the demolition of the existing unremarkable buildings (demolition of residential buildings also being part of the history of the Property) in favour of a remarkable building can arguably be treated as more true to the heritage of the Property. The conservation of the Property is fulfilled by restoring a physical presence that is commensurate with the geographic attributes of the Property at the top of the valley.7 (Emphasis added.)

The Tribunal was clearly impressed with the design for the new structure by Hariri Pontarini Architects. It seems to have taken to heart the district plan guideline that proposed replacement buildings for category “C” properties be “equally able or more able to contribute to the heritage character of the district.”

Perspective view of the proposed condo building on Dale Avenue

A good argument can be made that this case was wrongly decided. If the house at 7 Dale Avenue is indeed a significant heritage resource, then, according to provincial planning policy, it should be conserved. Granted, “conserved” might mean different things. But allowing the house to be torn down and replaced by a new apartment building of “physical presence” — supposedly harking back to a very different large, long-gone structure — seems to me an interesting, even inventive interpretation of “conserved”, but also a rather kooky one. The LPAT seems to have misconstrued the cultural heritage values at stake here.

No doubt the Tribunal, similar to the Stratford case from last time, was reluctant to gainsay the municipality and overturn the city’s hard-won approval for the project.8

The HCD Study, as accepted operating guideline, makes full allowance for demolition of structures in the interest of advancing the general and overall objectives of the HCD Study in the form of new buildings which will align with the heritage character of the district.

As such, the Tribunal accepts that City Council, as the authorized decision maker under the OHA, considered the evidence put before it and, despite mixed opinions placed before it, made the heritage value judgments which they are authorized to make. These judgments led them to authorize the demolition of the existing buildings on the Property and to authorize the proposed apartment building as fulfilling the objectives of the HCD Study and the applicable planning instruments.

… There is always a necessary judgment as to the heritage value of any given structure or cultural landscape as that relates to the community that the council governs.9

Had the city opposed the project, the outcome might well have been different.

The case might also be seen as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of rating schemes…

7 Dale Avenue, main entrance

Notes

Note 1: Conserved, as currently defined in the PPS means: the identification, protection, management and use of built heritage resources, cultural heritage landscapes and archaeological resources in a manner that ensures their cultural heritage value or interest is retained under the Ontario Heritage Act. This may be achieved by the implementation of recommendations set out in a conservation plan, archaeological assessment, and/or heritage impact assessment. Mitigative measures and/or alternative development approaches can be included in these plans and assessments.

Note 2: Dale Inc. and Dale II Inc. v. City of Toronto, July 4, 2019. LPAT case no. PL171267. See https://www.omb.gov.on.ca/e-decisions/pl171267-jul-04-2019.doc.

Note 3: The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe includes policy 4.2.7 “Cultural Heritage Resources”:

Cultural heritage resources will be conserved in order to foster a sense of place and benefit communities, particularly in strategic growth areas.

Note 4: Technically the plan is the South Rosedale Heritage Conservation District Study, completed in 2002 and adopted in 2003. A side-issue in the case, concerning the status of “old”, pre-2005 Heritage Conservation Districts, was discussed in an August 31, 2019 article on OHA+M.)

Note 5: The A-B-C rating scheme in the plan is apparently used in only one other HCD plan in Toronto (but may also be utilized elsewhere in the province?).

Note 6: Paragraph 159 of the decision.

Note 7: Paragraph 147.

Note 8: See the city staff report at https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2018/cc/bgrd/backgroundfile-119506.pdf.

Note 9: Paragraphs 150-152.