"What's past is prologue."[1]

"Stratford itself is the type of walkable wholesome town Rodgers and Hammerstein might write a musical about."[2]

Let’s face it — there is no small city in the province, or the country, quite like Stratford.

As Stratford, with neighbouring St. Marys, has just played host to the 13th annual Ontario Heritage Conference this past weekend, indulge me while I pay a personal, unabashed tribute to the Festival City.

Full disclosure: I’m a bit biased, having got my start in Stratford — in more ways than one. I was born in the brand new Stratford General Hospital (and grew up in the village of Milverton 25 kilometres to the north). A couple decades later, as a Summer Experience student, I began what turned into a career in heritage conservation working for the Stratford LACAC (Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee).[3]

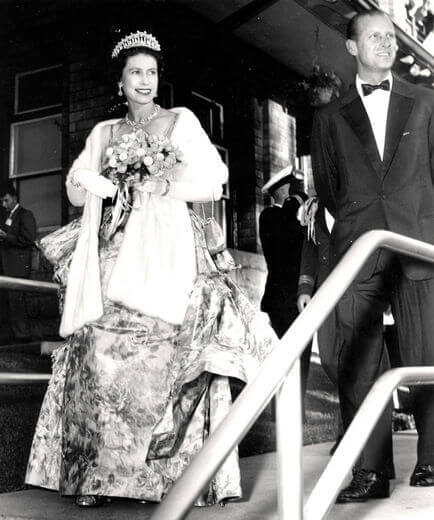

The Queen and Prince Philip visit Stratford in 1959

There were other firsts in Stratford in between: my first time in a movie house, now the Avon Theatre; my first time seeing Shakespeare on stage; my first (and only) time seeing Her Majesty drive by.

But back to Stratford and how it got its start.

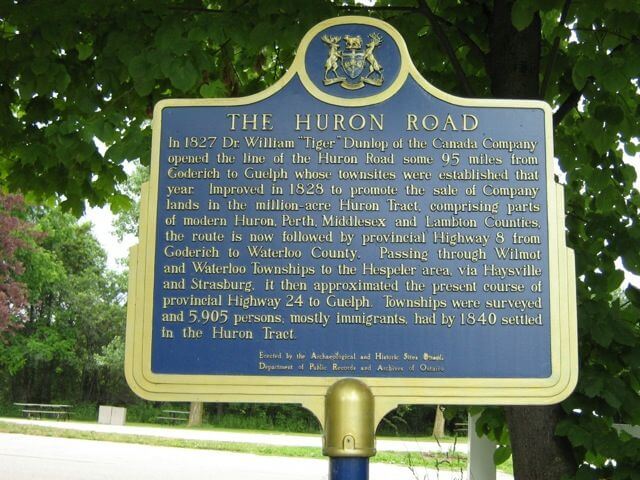

The Huron Road — the original road that opened up this part of the world, linking Guelph and the “frontier” at the western edge of Waterloo County to Goderich and Lake Huron — was hacked out in 1828. Where it crossed the Avon River, first called the Little Thames (in fact a tributary of the North Branch of the Thames), a settlement grew up with a grist mill and saw mill. And, of course, a tavern.

The beginnings of the name of Stratford lie buried in the silence of the past. The closest thing to documentation is an old tale about [Canada Company] Commissioner [Thomas Mercer] Jones who came one day from York bringing a painting of Shakespeare which he presented to Wm. Sargint, the appreciative Irish tavern keeper. Tradition says it was hung outside the inn which became the Shakespeare Inn and led to renaming Little Thames as Stratford.[4]

But what really put the little burg on the map was the railways — one in 1856 (on its way to Sarnia) and a second soon after (completed to Goderich in 1858) crossing the first, making an “X.”

Out of the wilderness of the Huron Tract rose a remarkable city. Part of the reason for the rise of its fortunes was the 19th century arrival of the Grand Trunk Railway’s locomotive repair shops.[5]

An early view of the Shops (in background

Other railways followed and Stratford became a great hub, attracting the “shops”, a mammoth locomotive repair facility that thrived from the 1870s through the first half of the twentieth century.

The mammoth 1907 Shops structure

Interior of the 1907 structure today

The shops were the economic engine of Stratford, which by 1885 had become a city. Industry rapidly expanded, especially the furniture-makers — by 1929 Stratford had no less than 13 furniture companies!

But even at the height of the railway era, the citizens of Stratford were not quite prepared to sacrifice a special place to the demands of industry. In the early 1900s the Canadian Pacific Railway proposed a line into the downtown that would have ravaged the city’s fledgling park system along the river. When the proposal was finally decided by referendum in 1913, parkland won over railway lines, by a margin of 127 votes.

The first of the iconic Stratford swans appeared on the river in 1918.

…[I]t was the decline of the [steam] locomotive industry in the early 1950s that motivated the city’s concerned residents to look for a new economic base. That they should think of a theatre was not so strange, for there had always been people here with the interest, the will and the commitment to see the arts flourish.[6]

With one bold stroke that has left our big cities gasping, Stratford, Ont., will this summer claim its birthright with a Shakespearean festival.[7]

And it started in a tent! A tent raised in Queen’s Park, the anchor of the Stratford parks system.

Then a few years later came architect Robert Fairfield’s tent-echoing Festival Theatre, one of my three favourite buildings in the city.

The other two? The majestic Perth County Courthouse by London, Ontario, architect George F. Durand, opened in 1887.

And of course the fanciful 1899 neo-Jacobean-slash-Picturesque city hall by Toronto architect George W. King.

Stratford City Hall fits into its market square like a hand in a glove.[8]

In a stirring key note address to the Ontario Heritage Conference last Friday, David Prosser, Literary and Editorial Director at the Stratford Festival, talked about the inspiration the city’s old buildings provide for the Festival’s artistic endeavours. And the payback to the Festival for its adaptive reuse of many older structures.

In all these cases, an old building has been given a new lease on life. But I feel as if some kind of benefit has also flowed the other way. I feel that a building itself – its history, its character, the bones of the past that you can still discern under every present-day face-lift – in some ineffable way informs the work that’s done in it.

Prosser finishes by making an eloquent plea for Stratford’s heritage as a driver of culture and creativity.

I believe that Stratford the theatre town is a far richer, more interesting place to live – a place more likely to attract people of imagination and creative enterprise – for having once been the Stratford renowned for furniture factories and railways. Our parklands, our architecture, the spaces created by our predecessors: this is our heritage landscape.That landscape played a significant part in enabling Stratford to become a centre for some of the finest theatre in the world, and a community that thrives culturally and economically. Let us always seek to make that landscape ever richer, ever more beautiful.[9]

Hear, hear!

Notes

Note 1: The Tempest, Act 2, Scene I

Note 2: Amy Alipio, Associate Editor, National Geographic Traveler

Note 3: I spent most of the summer walking up and down Stratford’s streets taking photos of houses, then writing about some of them in the local paper.

Note 4: Thelma Coleman, in The Canada Company, 1978

Note 5: Adelaide Leitch, in Floodtides of Fortune, 1980

Note 6: Richard Monette, in his foreward to Stratford: Its History and its Festival, Carolynn Bart-Riedstra and Lutzen H. Riedstra, 1999

Note 7: Maclean’s magazine, 1953

Note 8: Architectural historian Douglas Richardson — at least I think so. If he didn’t say it, he should have.

Note 9: See the full text of David Prosser’s remarks on May 13, 2016 at http://www.arconserv.ca/resources/show.cfm?id=21