Our topic for today — please don’t be scared away —

Is what the courts have had to say…

about the O-H-A.

AKA jurisprudence: how the courts and, from a wider perspective, our regulatory tribunals — the Ontario Municipal Board and the Conservation Review Board — have interpreted the Act and its regulations.

As we saw last time, during debate over Bill 60 ten years ago, a group of church organizations claimed that the legislation — specifically the controls on demolition of designated buildings — was unconstitutional because it violated the right to freedom of religion under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Although the bill was passed into law unaltered, no challenge of the kind was, thankfully, ever pursued. Would have made for a fascinating case though. Imagine the courtroom drama! And then the excitement of the court’s decision — the Act (demo provisions) upheld… or the Act struck down… or the Act struck down for faith group owners but upheld for everyone else.[1]

Not complaining, but there hasn’t been much courtroom, let alone courtroom drama, associated with the OHA. For a statute that’s been around for 40 years there are remarkably few court decisions. Probably this is because the legislation was, until Bill 60 came along, relatively weak, so property owners (the most likely challengers) didn’t see much at stake. Also that the two tribunals involved have, as intended, borne the brunt of what disputes there have been — and have handled these competently, with few errors in law that would open the door to review by the courts.

But there have been some interesting cases, and I’m not counting those that turned on procedural points like whether notice of designation was properly given or not. Let’s look at one, just decided this month: Foley v. Corp. of the Town of St. Marys.[2]

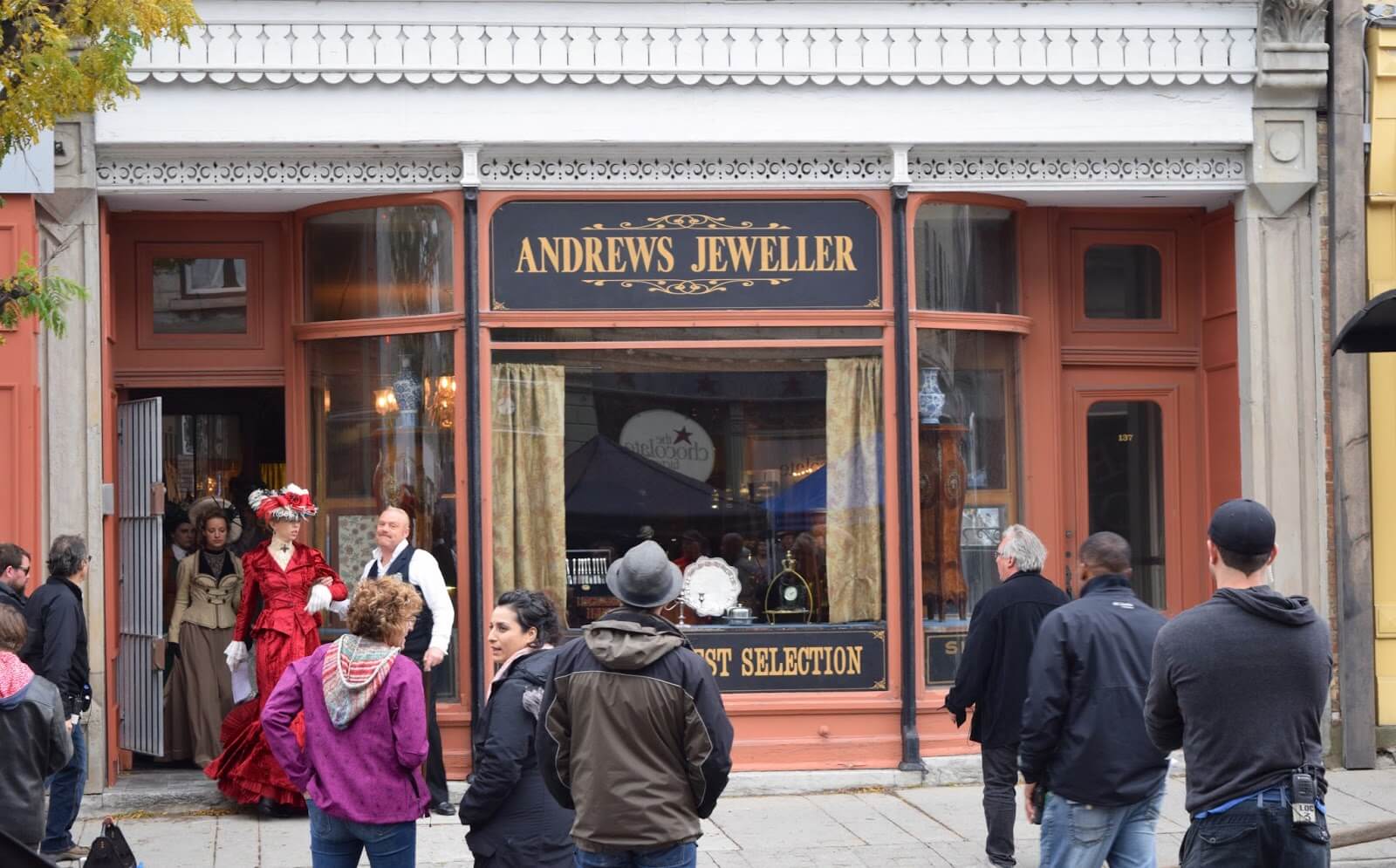

Andrews Jeweller building during shooting of Murdoch Mysteries episode, 2014

The case concerns the iconic Andrews Jeweller building in downtown St. Marys. The 1884 building is in the middle of a heritage conservation district but is also individually designated — outside and in. And it’s the “in” that led to the dispute here.

The designation by-law, from 2008, covers the building exterior and “all of the original interior features” from 1884. While these are not spelled out, the by-law has a schedule attached with photos of the interior, and the photos, not unlike the historical one reproduced here (although minus the jewellery!), show a wall clock, walnut cabinets and counters, and mirrors.

Interior of Andrews Jewellery store, courtesy St. Marys Museum

The owners argued that these features were chattels or personal property, not real property, and that their designation was invalid, since only “real property” including “all buildings and structures thereon” can be designated under the Act.

The back story here is that the out-of-town owners have been trying to sell the building for years and are convinced that the restrictions on the truly gorgeous interior are scaring off buyers.[3] After attempting in vain to get the Town to remove the designation of the interior, they sought redress from a higher power.

So the court was faced with the question — were the clock, cabinets, etc. personal property (not designatable), or were they fixtures, part of the real property (designatable)? In a different lexicon, moveables or immoveables?

From the leading cases on the distinction between chattels and fixtures, the court identified two principles as germane to the case:

- an object that is only attached to a building by its own weight is not part of the real property unless there is evidence to show it was intended to be part of the building

- an object is considered a chattel unless there is evidence it is affixed with the intention of improving the property or premises as a whole

Now the wall clock in the Andrews Jeweller building could simply be lifted off its hook, and this had been done for cleaning purposes. The counters were just sitting on the floor. Removal of the cabinets and mirrors would be more difficult but could be done without damage.

Nevertheless… the court concluded they were all fixtures:

The evidence establishes that they were designed and installed for the express purpose of attracting customers and selling jewellery through an enhancement of the realty. The wall clock, cabinets and counters were purposefully designed and built into the store for a specific purpose. They were used for that purpose and never moved again in over 100 years.

And so the owners’ suit miscarried.

A sensible result. It seems the test is not (the simpler) one of how easy a heritage element can be removed, but (the harder) one of intention and purpose of its installation.

I guess you could say that when it comes to designating interior features, you don't necessarily have to nail it to nail it. (Sorry.)

I’ll leave you to ponder the implications for other old stores and their counters and shelves, for old churches and their alters and pews, for old town halls with their wallclocks and furniture… et cetera. Does it matter if these things weren’t "original" but added later?

Andrews Jewellery building during shooting of Murdoch Mysteries, 2014

Notes

Note 1: In drafting Bill 60 the culture ministry sought a legal opinion on whether proposed tougher demolition controls would hold up and was advised to include “no compensation” provisions (OHA section 68.3); but compliance with the Charter was not considered.

Note 2: Superior Court of Justice File No. — 15-2635; dated October 9, 2015. Foley v. The Corporation of the Town of St. Marys, 2015 ONSC 6214.

The lawyer successfully arguing the Town's case was Eileen P.K. Costello, of the Toronto firm of Aird & Berlin. Note: The owners appealed the decision but the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal on a technicality in June 2016.

Note 3: The designation certainly didn't scare off CBC's Murdoch Mysteries when it came to town a year ago to shoot two episodes of their series, one involving a gang of female jewel thieves. The Andrews building, both inside and out, played... a jewellery store.