When we looked at the need for policies to protect heritage property owned by the province, we saw that the demolition of the old lunatic asylum in Toronto in 1976 was perhaps a watershed moment (see “Policies for the protection of provincially-owned property (part one)”, from May 31, 2015).

In the case of municipally-owned heritage, there are a couple losses that loom particularly large in the last 50 or so years. The first was in Kitchener, where the splendid 1920s classical revival-style city hall was demolished in 1973. The building presided over a great civic square, which was also lost — both replaced with a non-descript mall.[1]

Old city hall and civic square, Kitchener

The other was in Chatham in 1981 when the grand old Harrison Hall, Chatham’s city hall, fell to the wrecker’s ball. I remember the consternation this caused at the culture ministry in Toronto at the time. The Ontario Heritage Act (OHA) had been passed in 1975 and the revamped Ontario Heritage Foundation (now Ontario Heritage Trust) had grant money for preservation projects. But despite provincial and local efforts, council was not persuadable. Again, a mall rose from the ashes.

Harrison Hall, Chatham

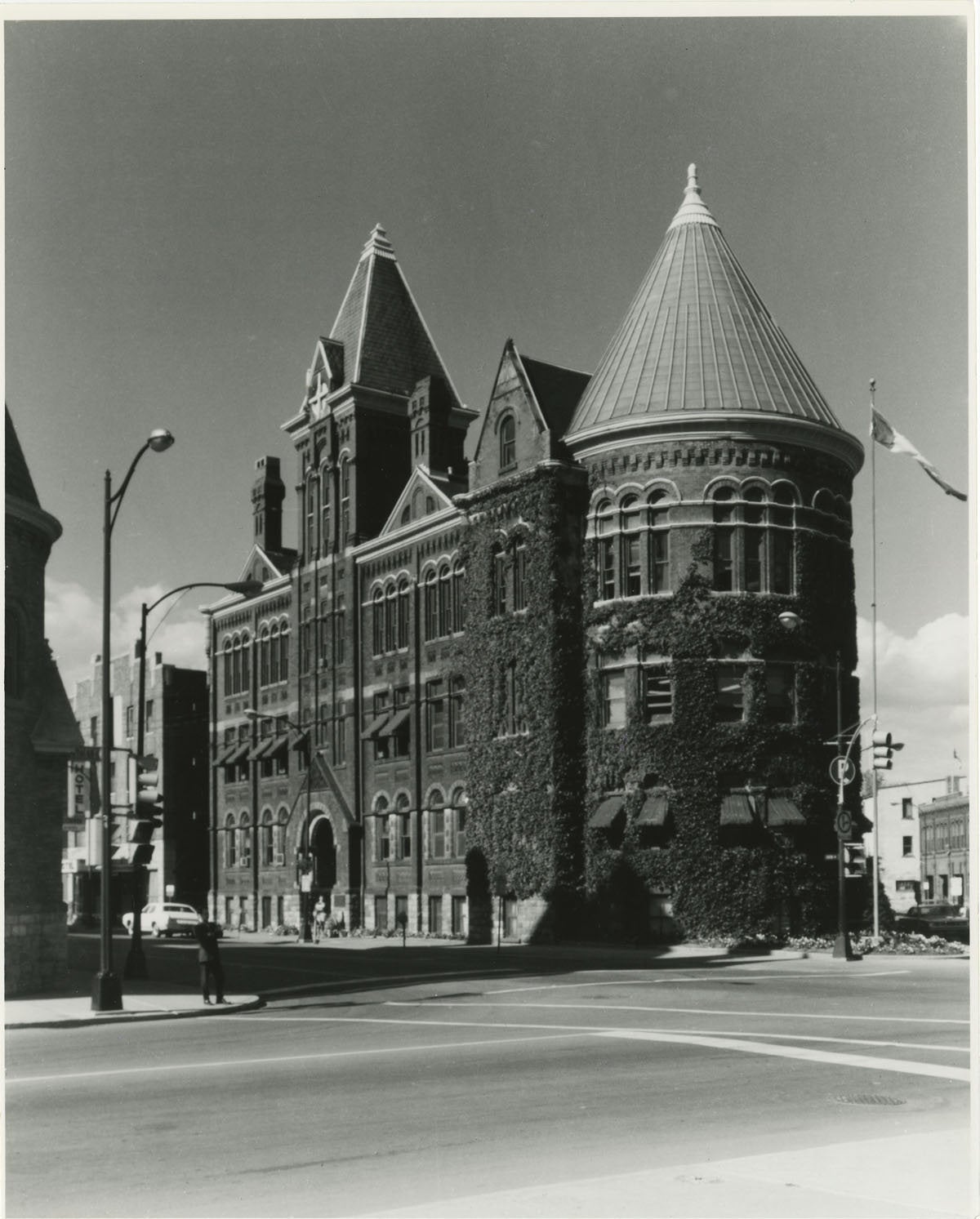

Then there are the famous “they-beat-back-the-philistines” stories from the 1960s and ‘70s — the saving of old city hall in Toronto is the best known. (In this case another downtown mall, the Eaton Centre, did not end up swallowing the building.) The 1899 neo-Jacobean (or Picturesque, take your pick) city hall in Stratford, and its triangular civic “square”, also narrowly escaped destruction in this period.[2]

Stratford City Hall from the rear showing part of Market Square

More recently, we have seen notable successes in rescuing civic buildings that were at risk, often as a result of amalgamations. My favourite is Victoria Jubilee Hall — the fight to save Walkerton’s old town hall gave birth to the local branch of Architectural Conservancy Ontario (ACO) and ACO now owns the building.

Victoria Jubilee Hall, Walkerton (you can probably guess its date of construction)

What do we learn from all this about how to protect municipally-owned heritage?

First, use of listing and designation is crucial. Even more so than with private property, as municipalities should be leading by example. Listing flags a heritage property and provides interim protection. Designation provides long-term protection. While it’s true, as we saw last time, that with these powers the municipality ultimately controls the levers, it must still follow the process set out in the OHA. It must at least consult with, and consider the advice of, its municipal heritage committee. In the case of de-designation (almost always a bad idea), its actions are also subject to review by the Conservation Review Board if there are objections (which there almost always will be). While it cannot be appealed, demolition of a designated structure is not something any city, town or township would contemplate lightly. Even alterations will be subject to sharp scrutiny. Here in St. Marys the Town proposed removal of a chimney of the designated town hall, creating a big fuss — and hasty back-pedalling.

Heritage district designation can be a powerful way of protecting and enhancing the municipally-owned “public realm” of an area — the streets, sidewalks, verges, etc. that contribute to its unique character. (Alternatively, or in combination with an HCD, some municipalities, like Kingston, use area-specific Official Plan policies for this purpose.)

Second, the importance of strong heritage policies in the municipality’s Official Plan — deriving from and building on those in the Provincial Policy Statement. These should include special additional policies that apply to heritage property in municipal ownership and public realm property. Here are two examples from Toronto’s recently adopted OP heritage policies:

- When a City-owned property on the Heritage Register is no longer required for its current use, the City will demonstrate excellence in the conservation, maintenance and compatible adaptive reuse of the property.

- When a City-owned property on the Heritage Register is sold, leased or transferred to another owner, it will be designated under the Ontario Heritage Act. A Heritage Easement Agreement will be secured and monitored, and public access maintained to its heritage attributes, where feasible. … [3]

Third, don’t expect the province to come to the rescue of civic heritage at risk. While I would like to believe the old Kitchener City Hall and Chatham’s Harrison Hall would still be standing if the OHA had had the provincial designation and stop order powers it does today… well, that’s hypothetical, but also fanciful. (That said, a timely provincial stop order should not totally be ruled out, and sometimes all it takes to turn the tide is a little extra time.)

Not to be overlooked is the Ontario Heritage Trust’s heritage conservation easements program, which further protects many municipally-owned structures such as Stratford City Hall and the Wellington County Courthouse in Guelph.[4] The province — both the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport and the Ontario Heritage Trust — is of course also a great resource and active promoter for the municipal policies and actions discussed above. And then… there’s provincial public infrastructure funding!

Finally, and most especially, the role of citizen vigilance and activism, which has effectively preserved so much of our civic (and non-civic) heritage, often through hard-fought battles — whether for the town hall on the square, the bridge on the river or the by-law or policy on the books.

Notes

Note 1: Kitchener’s decisions here were approved by public referendum.

Note 2: Architectural historian Douglas Richardson memorably referred to Stratford City Hall fitting into Market Square ”like a hand in a glove.”

Note 3: Policies 8 and 9 under “General Heritage Policies.”

Note 4: The Trust’s easements program is generally a reactive, rather than proactive, one, and because of funding limitations has become over the years less focussed on cultural heritage and more on natural heritage.